In the spring of 2007, the U.S. Supreme Court forged a new precedent for the matter of "obviousness"1 as it pertains to patents in the unanimously decided KSR v. Teleflex ruling. Generally, to be granted a patent, an invention must have a non-obvious improvement over a previous invention. The first time the court weighed in on a definition for obviousness was the Hotchkiss v. Greenwood case (52 U.S. 11 How. 248 248 (1850)) when the nine justices had to decide whether manufacturing doorknobs out of clay or porcelain, rather than metal, was a patentable invention. They didn't rule in favor of the clay and porcelain because the "innovation" of making an existing product out of a new material was "obvious." Through 150 years of judicial evolution, the "obviousness test" became stricter, but with the KSR decision, a significant change took place in the specificity of what a patentable invention may be. Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote, "Courts... have been upholding patents for technologies or designs that didn't need them, that would have been developed 'in the ordinary course' of events."2 Kennedy's statement that nothing can be new unless it happens outside of the "ordinary course" of events, narrows down the possibility of anything New ever occurring at any point in time considerably. If Kennedy's words are taken literal extreme, they imply that Newness is an utter impossibility.3 It's as if the justices know, in their heart of hearts, that there are no New Ideas. There are no intellects that I respect more for their sheer depth and fecundity than Supreme Court Justices, so if you're like me, you probably get the feeling that we can safely start to rethink concepts such as avant-garde.

Our epistemological conceit of believing that we can create New Ideas reached an apex with the avant-garde, but the mythology of the movement had its eventual detractors. Art critic and Postmodern theorist Rosalind Krauss couches her 1981 essay, "The Originality of the avant-garde: A Postmodernist Repetition,"4 in the impossibility of the New. The work, which was initially published in October, was later included in her aptly titled collection, The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths and lives on as a seminal deconstruction of the belief in the artist as absolute creator. The method and philosophy of the Modern artists necessitated their reliance on their selves. "The self as origin," Krauss wrote, "is the way an absolute distinction can be made between a present experienced de novo and a tradition-laden past. [...] More than a rejection or dissolution of the past, avant-garde originality is conceived as a literal origin, a beginning from ground zero, a birth." (157) But, as Krauss details in her essay, avant-garde artists were actually copying each other. In their quest for the unqualified origins of artistic creation they reached the minimalism of the grid5, an inert and repetitive organization of lines on a plane. Krauss wrote that if avant-garde can be seen as "a function of the discourse of originality, the actual practice of vanguard art tends to reveal that 'originality' is a working assumption that itself emerges from a ground of repetition and recurrence," (157) and that repetition and recurrence yielded the grid. Literally described, what artists began drawing and painting amounted to representations of graph paper. As ironic as it may be, one of artists' primary attempts to create the New generated what was arguably the pinnacle of creative lifelessness in popular art-making for the 20th Century.

But we still go on creating and it's not as though the world ended when the first grid was called a masterpiece. The non-existence of New Ideas never was a problem, and last I checked, artists were still making art and contributing to the gross national products of their respective countries of residence. "Perhaps it is because of this sense of a beginning, a fresh start, a ground zero, that artist after artist has taken up the grid as the medium within which to work," wrote Krauss. (158) We, as humans, need to create new things - or at least believe that we are - and the grid was just a rather grotesque genre born from our innate desire to attempt to improve upon our predecessors. In my Facebook discussion, Steve Locke, a Boston based artist and art education professor, said "I don't know if there are any new ideas, but I don't think that is a bad thing or a demonstration of the end of something. I think originality and "newness" are not to be valued of themselves, nor are they signs of innovation. I think the important thing is that we learn more, we discover more, and we apply that knowledge to the forms we have."6 Grids were just a form where we decided to throw out every conscious influence from the past.

So whether New Ideas exist is not important. Whether more ideas are available to us, however, may be a matter of survival for society. There is that saying, "Those who don't know history are doomed to repeat it," but the ignoramuses are not only doomed to repeat, but also limited in their comprehension of the present as they are unaided by any understanding of the past. In his Configurations of Culture Growth7 (1944), the cultural anthropologist Alfred Kroeber assessed the vitality of civilizations by considering the appearance of famous creators from that society's history. He found that a civilization's competitiveness increased when, unsurprisingly, it had higher numbers of powerful brains and decreased when it had less. Without creativity, there would be no diversity of thought and therefore no evolution of ideas; and without the evolution of ideas, civilization would eventually decompose. We'd either become extinct or be enslaved by robots.

Whether there are New Ideas, our survival depends on our ability to generate ideas and concepts. The lens through which we view the world is constantly changing as our culture evolves and we forget and relearn, confuse and reinterpret. The author E.L. Doctorow, when discussing his book Creationists: Selected Essays 1993-2006 - a plenary consideration of creativity's role in culture - said "[c]reativity is the reigning enterprise of the human mind. It affirms that what we know, we know by what we create."8 Everything we know, we know because we've observed, interpreted and considered and then subsequently regurgitated and shared; and through that process, we give life its significance. "There's kind-of a bare world out there," Doctorow said, "that has no meaning until we imbue it with meaning, which is what artists do, which is what writers do, which is what scientists, engineers and to a certain extent, politicians do. We all make compositions of our lives every moment of our waking and sleeping." Don't ever stop creating.

1 - I think we can all agree that New Ideas cannot be obvious. Otherwise they would not be new.

2 - Bennett, Drake. "Patently Obvious." The Boston Globe. 6 May 2007.

3 - Could Aple have obtained a patent for their rotational interface after Kennedy's redefinition of obviousness? It doesn't seem like it.

4 - Krauss, Rosalind. "The Originality of the Avant-Garde: A Postmodernist Repetition." From The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths. MIT Press, 1986. Accessed on Google Books.

5 - Krauss wrote: "Aside from [the grid's]near ubiquity in the work of those artists who thought of themselves as avant-garde - their numbers include Malevich as well as Mondrian, Léger as well as Picasso, Schwitters, Cornell, Reinhardt and Johns as well as Andre, LeWitt, Hesse and Ryman - the grid possesses several structural properties that make is susceptible to vanguard appropriation."

6 - Locke gave the example of portraiture for a form we have: "Portraiture has changed based on what we know about the human person. Rembrandt and Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle are both dealing with imaging the human person - one in paint and one using DNA imaging. Is the idea different? Not really, but the knowledge has changed the form."

7 - Simonton quotes from Kroeber on page one of his Origins of Genius: Darwinian Perspectives on Creativity to qualify the book.

8 - E.L. Doctorow in conversation with Tom Ashbrook on the WBUR/NPR talk show On Point. Wednesday, 20 September 2006.

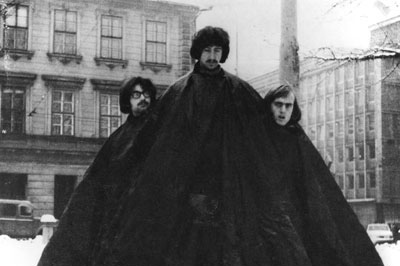

- Slovenian artist group OHO perform Mt. Triglav, 1968

- Slovenian artist group Irwin perform Mt. Triglav, 2004

- Slovenian artists Janez Janša, Janez Janša, Janez Janša perform Mt. Triglav on Mt. Triglav, 2007

NEW IDEAS. NO, I MEAN IDEAS THAT NO ONE HAS HEARD OF BEFORE. by CHRISTIAN HOLLAND in issue #97

THERE ARE NO NEW IDEAS. PART 2 by CHRISTIAN HOLLAND in issue #98

THERE ARE NO NEW IDEAS. PART 3 by CHRISTIAN HOLLAND in issue #99

All images are via Aksioma.org.