Black Drop (2012) by artist Simon Starling appears conventional enough, as a documentary film. In it, Starling chronicles the transit of Venus and its surprising relationship to the history of the moving image. The film is a straightforward but wry commentary that pulls cinematic history as far back as the camera obscura of the 1500s to a celestial, cosmic beginning when astronomy and astrology were closely linked. It’s a dense and heavily researched film that launches some complex ideas. In it, Starling cites two early photographic and cinematic works: a book, The Moon: Considered as a Planet, a World, and a Satellite by astronomer James Nasmith, which included photographs of plaster lunarscapes Nasmith made from his own observations of the moon, and the cinematic work of Georges Méliès, A Trip to the Moon, still considered a hallmark of cinematic narrative and special effects. The referenced imagery could not appear more different. One is the result of scientific inquiry, the other fanciful entertainment. Yet in terms of process and construction, the two are remarkably similar. The film is full of subtly inferred ironies and becomes something of a lodestone for the exhibit as a whole.

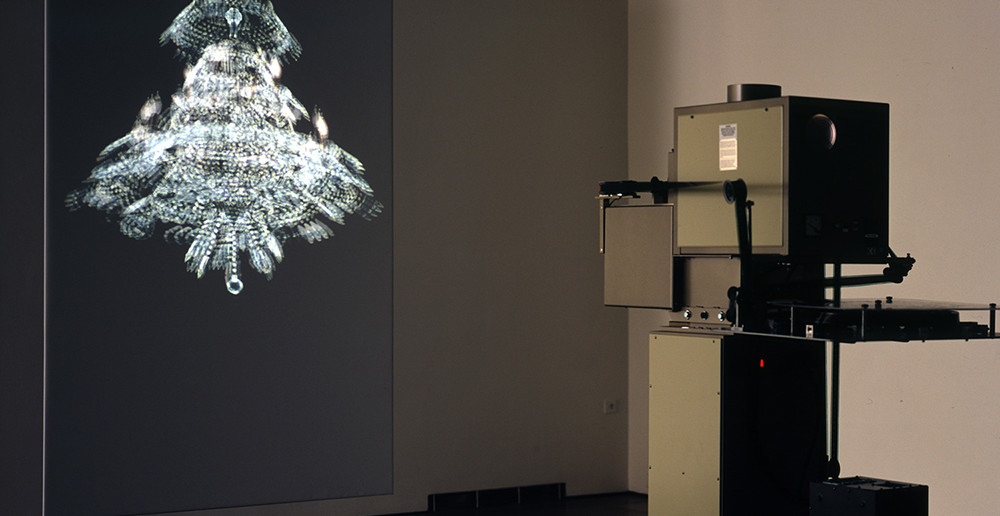

Installation views of Rodney Graham's Torqued Chandelier Release, 2005.

Rodney Graham (b. 1949 Abbotsford, British Columbia, Canada) Torqued Chandelier Release, 2005 35mm silent colour film (5min), purpose built projector, screen

Screen: 305 (h) x 183 (w) cm.

© the artist; Courtesy the artist and Lisson Gallery, London

Other works in Cross’s show highlight the whole apparatus of projection and include their custom made projectors. Canadian artist Rodney Graham’s Torqued Chandelier Release (2005) is a looped 35mm film of a spinning chandelier. The footage was shot with the camera on its side and the immense screen on which it is projected is vertically oriented. The work’s custom built projector sits at the back of the viewing space; its various loops and thimbles to control the celluloid tension and speed are reminiscent of a sewing machine and mirror the tension and velocity of the chandelier imaged on screen. It’s a luscious image and the whole effect, pure spectacle.

Italian artist Rosa Barba’s piece The Long Road (2010) is a looped film of an abandoned racetrack in the American Midwest. Shot from above, the track is reminiscent of Land Art and appears like a giant drawing inscribed on the ground. Aerial footage is intercut with footage shot on the road itself—low to the ground zooming through the curve of the track. A large 35mm custom built projector whirs and clicks as the looped film moves through the illuminated lens. Seen from behind the projector, the loop of film bisects the screen like the giant slash of a "Do Not Enter" sign. The slash underscores some of the work’s themes—the line of road, time, and the dissonant line between image and actual experience.

A second, smaller work by Barba, Stating the Real Sublime (2009), installed in an adjacent gallery animates this dissonance. Composed of a smaller 16mm projector which is suspended precariously from the ceiling by the fully exposed, 16mm loop of celluloid film itself, the whole contraption in endless motion seems to reach impossibly towards its own projection—a moving target, registering the accumulating dust and scratches in a fading box of white light. Its self-destruction seems imminent; the whole thing might crash to the floor pulled as much by the weight of its metaphoric trope as the weight of its projector.

Trained as a painter, artist Tacita Dean is drawn to the photochemical process of analog film. Varied by film stock, processing techniques and impacted by time, Dean likens this process, with all its flaws and hand-made qualities, to something alchemical. Her subjects are often elusive, fleeting natural phenomena, or ruins or relics on the verge of disappearance. The Green Ray (2001), a 2 ½ minute 16mm film witnesses a sunset and the natural phenomenon called the green ray. Most often seen by sailors and pilots where clear horizons and atmospheric conditions are hospitable, the green ray is a momentary green flash in the last rays of the setting sun as its light is refracted into its component colors. Glimpsed in Dean’s work, the celluloid of the film seems as elusive, magic and rare as the phenomenon itself.

Lisa Oppenheim, a still photographer and film maker, "teases apart the individual steps of picture making, wringing from them … a surprisingly broad range of meanings."1 Her two channel video installation, Smoke (2013), features imagery originally culled from a variety of internet sources. The digital images were transferred to 35mm film; then each frame was individually printed, exposing and solarizing the photo paper with various forms of firelight (fire, blowtorch, etc…) In a third step, the images were scanned and compiled into a digital animation. The final result, with its long and multi-iterative process, is the show’s most sensual, abstract, and immersive work.

Matthew Buckingham (b. 1963 Nevada, Iowa)

False Future, 2007

Continuous color 16mm film projection with sound, folding chairs, canvas, steel cable

Dimensions variable

Courtesy the artist and Murray Guy, New York

[1] Brian Sholis, "Lisa Oppenheim: Elemental Process," Aperture Magazine Blog, http://www.aperture.org/blog/lisa-oppenheim-elemental-process/

[2] Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, Reflections on Photography, (1980) pg. 80

"The Dying of the Light: Film as Medium and Metaphor" is on view at MASS MoCA through mid-February, 2015.

For more information visit massmoca.org