The huge influx of artists and intellectuals from Europe to the United States during the world wars, which created what seemed to be a transfer of power from Paris to New York, is a well-known story. There are endless books about the NY School, the European artists that gave Americans confidence, the jittery American artists that never believed that their work had gravity, and how painting—the subject is almost always a painting—changed and grew when it crossed the Atlantic. American art became something to be grateful for rather than to work against. 1945 was almost a hundred years ago now and its art historic specter will probably be with America for another hundred years.

Destroy the Picture: Painting the Void, 1942-1962, curated by Paul Schimmel for the Los Angeles MOCA (it also traveled to the Chicago Museum of Contemporary Art, which is where I saw it), breathes a bit of fresh air into this old story. This show explores the percussive nature of literally breaking the picture plane; an aesthetic inevitability that is attributed to the psychological repercussions of World War II. Destroy the Picture is not based around the myth that New York stole Paris’s mojo, instead it expands this conversation by treating the work created by artists from Japan, Germany, Austria, Italy, and Spain as part of the same story. The show’s map appropriately matches the war’s full span.

Lucio Fontana, Concetto spaziale, Attese 58 T 2 (Spatial Concept, Expectations 58 T 2), 1958

Lucio Fontana, Concetto spaziale, Attese 58 T 2 (Spatial Concept, Expectations 58 T 2), 1958Fondazione Lucio Fontana, Milan, Italy

The void is a metaphor for the optical plane as well as the empty space left in artist’s souls after the experiences they survived. The show makes you feel like you’ve been punched in the gut. These artists lived through some serious business and they’re trying to explain in ways that should affect you if you have any empathy. Some of the work strays a bit close to art therapy, but the traumas that are being treated are a bit more than private struggles.

The formal specificity of Destroy the Picture and the careful selection of each painting reinforce the notion that these abstractions have everything to do with skin and the body. These works attacked the body by attacking the canvas, metaphorically treating it as a piece of meat, with disinterest in how vile the depiction had become. This eventually became too distant for some artists, morphing into a more immediate and visceral art, like Viennese Actionism. Metaphors for slaughter and bodily mutilation creep up over and over again in Destroy the Picture. While it is disturbing, it’s nothing compared to the literal actions of an artist like Hermann Nitsch, which are mentioned but not explored in Destroy the Picture.

I can’t help thinking about PAINT THINGS: beyond the stretcher when considering Painting the Void. Beyond the obvious implications for painting’s scope, the two shows both explore politics through encoded and original material formats. Where PAINT THINGS is more post-modern (I hate using that term so loosely, but it is a politics that is undeniably "after" the "modern") in feel, Painting the Void is certainly high-modernism. Global art from the 1950s attempted to respond appropriately to the horrors of the final war at the end of all history. Adorno’s much-quoted statement about poetry after Auschwitz greets us at the show’s beginning. These artists were wrestling with this same notion of what is appropriate now that we’ve been terrified out of our wits by seeing the best minds of our generation die.

There was obviously more than one way to respond to those events. While the mid-century artists of Destroy the Picture were engaging with the void, your average equable American was living in the era of exotic tiki parties, rock and roll dancing, lounge music, big cars, suburban expansion, and general economic comfort. But the separation between these works and that cultural detachment is not accidental, nor is it fleeting. It took years of studied and determined engagement with the repressed fears of humanity to create these paintings.

The politics of exhibitions like PAINT THINGS (1 and 2), This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s (1 and 2), or NYC 1993: Experimental Jet Set, Trash and No Star (1 and 2) can be briskly described as personal politics. This phrase should imply the derision coming from the more conservative among us, but there is nothing in these shows that suggests that the world will be saved by a unified movement in art.1 The political implications are more intimate than global and the rights of one person to be considered a full member of society trumps any universal myth proclaiming the end of history.

The artists of the late twentieth century, working decades after high-modernism, don’t need to attack suburban politics or try to shock those same suburban moderates into engaging with the void. Even if and when they did shock the general audience, they insisted (radically I may add) to represent themselves and their political interests directly rather than through a caucus. The failure of all-embracing global revolution can be inferred from these shows if you consider them a reaction to the politics of Destroy the Picture.

That said, those that still chase global enlightenment through art could easily mock any of these artists as practicing a politics that doesn’t reach outside the studio. The artists in Destroy the Picture believe that they had more implications than just how studio practice changed through time. It’s debatable if someone like Otto Muehl reached the global audience or healed anyone. We can say that his experience should be a better-known element in the history of art and that such a meticulous show as Destroy the Picture benefits all of the various stories of post-war art.

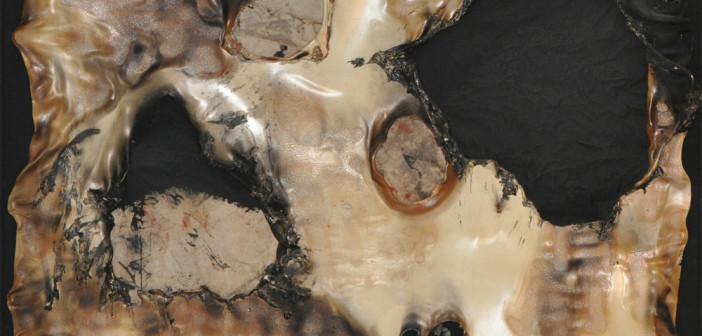

- Alberto Burri, Combustione Plastica, 1958. © Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini Collezione Burri, Città di Castello – by SIAE 2012

- Installation view, Destroy the Picture: Painting the Void, 1949-1962, MCA Chicago. Photo: Nathan Keay, © MCA Chicago

- Lucio Fontana, Concetto spaziale, Attese 58 T 2 (Spatial Concept, Expectations 58 T 2), 1958 Fondazione Lucio Fontana, Milan, Italy

- Salvatore Scarpitta, Sun Dial For Racing, 1962. Krannert Art Museum, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Festival of Arts Purchase Fund. © Estate of Salvatore Scarpitta

- Yves Klein, Untitled Fire Painting (F 13), 1961. © Yves Klein, ADAGP, Paris

- Lucio Fontana, Concetto spaziale 57 CA 3 (Spatial Concept 57 CA 3), 1957. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, gift of Morton G. Neumann, © 2012 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / SIAE, Rome.

- Shozo Shimamoto, Taiho no sakuhin (Cannon Picture), 1956. Private collection, courtesy of Axel Vervoordt Gallery, Antwerp. © Associazione Shozo Shimamoto.

[1] Unless you count the reaction to AIDS in these shows as an attempt to save the entire world through a unified art movement, but even that is a very specific set of goals which are not universal in nature.