If you’re in the mood for Neo-Victorian drag iconography torn from the pages of comic book fantasies (and, let’s face it, who isn’t?), then Dress Up should be your next destination. On view now through September 10 at Panopticon Gallery, this exhibition takes performativity, performance, and change-of-clothes identity categories as its fodder for play. And the play’s the thing! You might just find yourself feeling surrounded by a cast of actors in line for the next make-or-break audition, but the heightened sense of amusement and plain old good fun is catching. Fair warning, gallery-goers. Panopticon is a hallway in a fancy-pants hotel, not a sacred space set aside especially for the commercialism of high art. Taking its name from the prison designed by Jeremy Bentham in the late 18th century, a concept that would ground Michel Foucault’s work on discipline and docility, you may wonder if you’re being surveilled, subject to the same mechanisms of the camera as the photographs around you. So be sure to wear your cape and mask for a stroll down this hallway. You’ll be in good company.

Dress Up features artists Keiko Hiromi, whose series of drag queens I’ve long admired, and Eileen Clynes, whose knack for creating droll religious icons is boundless. Also in the bunch are controversial, postmodern portraitist Rick Ashley (as Tim McCool would say, "when in doubt, blame postmodernism"), and Finland-based duo Saara Salmi and Marco Melander, progenitors of the fantastical cabinet card studio Atelieri O. Haapala. One would think that an exhibition on performativity would be excessively theoretical or academic, but Dress Up takes a lighthearted approach that packs a punch of digital color par excellence. It’s refreshingly vibrant, and only sometimes oversaturated, all to good effect. By now we’ve grown accustomed to rampant oversaturation, much of it done poorly, and an art world that is rabidly hostile to it, and not always with good reason. But this exhibition bucks both trends. It is smartly done. Clynes’s iconography, the brightest in the bunch, benefits from its hyperbolic saturation. Christian religious icons have long held symbolic meaning in their palettes, after all. Admittedly, she’s preaching to the choir in my case. I am an unabashed fan of bold digital color. But while you may not share my sentiments, I think you’ll agree that there is plenty worth seeing in Dress Up.

Courtesy of the artist and Panopticon Gallery

Keiko Hiromi, for one, has a keen eye for all manner of lighting, be it spotlights or stage lights, photographic flash, vanity mirror bulbs or dressing room lamps. This aesthetic savvy serves her well. Hiromi works in the sparkly, but ever dimly lit drag queen club in downtown Boston, Jacques Cabaret, an establishment with a history spanning as far back as 1931. Her documentary photographs of the girls there are as much about individuality as performance. Hiromi captures them onstage and backstage, presenting a full picture of the queens’ transformation through makeup, dress, and other accoutrements that complete their metamorphosis into very different versions of themselves. The mirror is ever present in these photos, a constant reminder that the self is a social presentation. In her close collaboration with her subjects, Hiromi parallels Susan Meiselas’s work with carnival strippers. Hers is not a judgmental eye, but one that finds pleasure in the playfulness of "tap that" booty shorts and skintight leotards featuring two perfectly placed roses at the neckline.

Eileen Clynes and the Atelieri O. Haapala duo take an approach that more readily calls to mind Cindy Sherman or Renee Cox than stripteases. But I would be lying if I said that the reimagined personage of Mata Hari does not make an appearance. Clynes and Atelieri O. Haapala clearly believe that sometimes the clothes do make the man, or woman, or dancer-cum-spy, as the case may be. The fictive studio’s photographs are a veritable masquerade of historical characters who don contemporary (and figurative) masks, mixing and matching eras without a care in the world. Everyone from Marlene Dietrich to Marie Antoinette to a complete Vaudeville act have been invited to the party, but not as themselves. There’s a Steampunk style in these prints, including one of the duo themselves on expedition in Egypt, that will find an audience beyond photographers and photography collectors.

Courtesy of the artist and Panopticon Gallery

Clynes’s work also has the look of the studio portrait. Her saints stand against vivid backdrops, framed by elaborate, digitally-generated borders. They have decidedly political overtones for inventions of the imagination. Saint Ortho, patron saint of birth control, is a personal favorite. A "powerful advocate for women," she suspends her rosary in front of her womb, surrounded by all the trimmings of birth control pills and packets. Like her fellow saints, her wall text includes a prayer card: "Please enlighten those with political and religious agendas who wish to control my right to take birth control. Amen." But not all of Clynes’s prayers are as sober. The King, that patron saint of "taking care of business," will reportedly "strike a chord down upon thee with great gyration and furious anger" on any who step upon his blue suede shoes (or even so much as try!). Flaming heart ablaze, he holds the neck of his guitar gingerly, his fingers placed in such a way that the middle one is most extended. St. Sebastian is a hunky soldier, Jesus brandishes a rhinestone-studded rifle, and Joan of Arc is all too serious for my liking (although, to be fair, she is on fire).

Courtesy of the artist and Panopticon Gallery

Beyond the fun, I feel that I might have missed the point. Do these photographs give the lie to portraits, identity, religion, all of the above? I can’t really say. But the work I find most cryptic is not Clynes’s, but Rick Ashley’s. There is a painterly quality to Ashley’s images (unsurprisingly, as he is also a painter), with his diner scene on view recalling Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks. But because his subject is a mentally challenged man in a Superman costume, complete with cape and comic book, the meaning of Ashley’s images is somehow up for grabs in a way that is not all fun and games. I could certainly see how his portraits might make viewers uncomfortable in the same way that exploitative or otherwise voyeuristic work often does, but I couldn’t quite bring myself to believe that Ashley was either of those things himself. So I did some research. Once I had weeded through the Rick Astley search results (remember him?), I learned that Ashley had begun his series in response to an instructor’s assertion that poses are what make great portraits. Ashley disagreed, photographing his subject Michael in elaborate, often pretentious poses, to make his point. The Superman suit, it turns out, is Michael’s favorite outfit.

Does that fact shine light on Ashley’s photograph of Michael as Superman, seated in his wheelchair beside a fireplace and stuffed dingo, looking contemplative? I’m not sure. Apart from the various cultural prejudices about dingos, and I’m no expert in that, Ashley’s portraitSuperman with Dingo would appear to rely on our shared assumption that Michael is not what he pretends to be through his poses, neither contemplative nor Superman. But why do we believe that? Is it because no one is really capable of being Superman, after all, or because Michael is disabled? If the former, then why must Ashley photograph a mentally challenged individual to make his point about portraiture? His Dress Up cohort investigates similar territory in vastly different ways. If the latter, then what does that say about us? None of us can be certain what makes a great portrait. It may not be mere poses or postures, but the converse idea, that the portrait must reveal something true about the subject, seems misguided. And wholly out of place in this exhibition.

But that’s yet another reason I would urge you to go see Dress Up for yourself. See what you think, and if you figure it out, by all means report back. An exhibition that can provoke questions, even those motivated by discomfort, is in one sense a real success. Dress Up benefits from being able to do all of that while retaining its lighthearted, fun and funny, playful vibe. My only complaint is that our viewing experience is limited by and to a hallway. Give this masquerade the ballroom it deserves, I say! Or, you know, a gallery.

- Keiko Hiromi, Chris in the Mirror, 2012 Courtesy of the artist and Panopticon Gallery

- Eileen Clynes, Saint Elvis, 2012 Courtesy of the artist and Panopticon Gallery

- Eileen Clynes, Saint Guadalupe, 2012 Courtesy of the artist and Panopticon Gallery

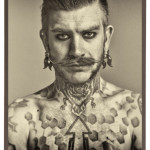

- Atelieri O. Haapala, Anna Fur Laxis, #1, 2011 Courtesy of the artist and Panopticon Gallery

- Atelieri O. Haapala, The Baron #2, 2012 Courtesy of the artist and Panopticon Gallery

- Keiko Hiromi, A Portrait of Katya, 2012 Courtesy of the artist and Panopticon Gallery

- Rick Ashley, Superman with Dingo, 2012 Courtesy of the artist and Panopticon Gallery