The Lane collection of photography by Ansel Adams on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston is absolutely breathtaking. But in a way that one might not expect. Envisioning rooms filled with beautiful images of nature created by a monumental figure in the history of photography, one receives more than imagined. In this mindfully installed exhibition, one gains insight into the man behind the masterpieces that people world-wide have come to know and love. Winding through the exhibition, one discovers not only a technical genius who harmoniously composed images with the sensibility of a pianist, but also a humanist, a humorist, and a joyful gentle being that cherished the fragile and temporary essence of life.

In his early silver-gelatin prints of Native Americans in New Mexico, one finds an inquisitive photographic perspective, yet a soft reverence for a dying culture with a strong spiritual connection to nature. In “Eagle Dance, Tesuque Pueblo, New Mexico” (1929), a dancing man and his shadow mirror an eagle in flight. Photographed from the back, while leaning forward, he spreads his feathered arms upwards from his sides, becoming the eagle, the Native American symbol of courage and bravery. Ironically, the eagle gracing the seal of the United States, a culture which separates itself from nature, constitutes that America “ought to rely on its own virtue”. In an image of five indigenous men engaged in a ceremonial dance entitled “Indian Dance, San Ildefonso Pueblo, New Mexico” (1929), Adams photographs the indigenous people as indifferent to the photographer and his camera. Their glances appear inward as they rhythmically perform a spiritual ritual which is consistently fading.

Some of Adams’ photographic explorations of the 1930s taken in San Francisco and Los Angeles expose a wonderful sense of wit with a hint of sarcasm. In “Americana, Cigar Store Indian, Powell Street, San Francisco” (1933), a life-size wooden statue of a Native American wearing a headdress and traditional clothing holds a cigar in his mouth while extending his right palm, as if begging for money. To his right is a telephone booth advertising “The Bell System” and several magazines including “Life”, “Time” and “News Week”. Pinned next to the emblem of an eagle on the Native American’s chest is a sign with an eagle in the center of a circle. It reads “NRA member”. To the right of the circle is a quote stating “We Do Our Part”. Adams reflects the fact that indigenous people have become powerless over the transformation of their land. The telephone, the English language in print, and the “freedom” to own guns have taken charge.

While working as a collections photographer in San Francisco, Adams shot “Museum Storeroom, De Young Museum, San Francisco” (c.1935), a photograph with a behind-the-scenes perspective. Figurative sculptures from various time periods and cultures, brought together in one area, appear to engage with each other. An ancient Greek Kouros smiles at the flailing legs of an overturned female as Hermes admires a Kore to his left, while holding the young Dionysus. Away from the viewing public and the eyes of critics, these sculptures appear to take on identities of their own.

“Discussion in Art, San Francisco” (1936) shows two men talking in front of a Madonna and Child painting at a museum gathering. Engaged in discussion, one man leans forward, while tugging at the lapel of the other man’s jacket, which holds a white flower. The gestures of his right hand echo the hand of Christ reaching up towards his mother while his left hand almost mimics the right hand of the Madonna. The form and tone of the white flower on the man’s lapel visually connects with the folds in the white cloth wrapped around the infant Christ. Although these men do not appear to be discussing religious matters, Adams’ photograph visually captures one of those moments when life imitates art.

While viewing photographs made on his journeys into nature in states like Alaska, Washington and California, one can hear Adams playing piano on a video (in an adjacent area) and sense the tonal gradations in his photographic experimentations as rhythmic patterns within natural compositions. With a calm disposition, Adams gently states that a photograph is like a musical composition, while each print made from the photographic negative is an individual performance of that composition.

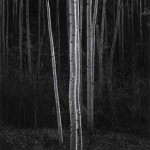

In Ansel Adam’s tone and spirit - as in his silver-gelatin prints of Native Americans or his glossy, sharply focused black and white photographs depicting variations of light and texture upon weathered architectural structures, mountainous terrains, inspiring trees and plant life, silvery-toned rocks, and bodies of water reflecting the sky and the subjects of its surroundings - one observes his great respect for life and remarkable aptitude for recording some of the beautiful miracles blossoming each day in America.

- Ansel Adams, Aspens, Northern New Mexico, Gelatin silver print, 1958.

- Ansel Adams, Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico, Gelatin silver print, 1941.

- Ansel Adams, Eagle Dance, Tesuque Pueblo, New Mexico, Gelatin silver print, 1929.

Links:

Museum of Fine Arts

"Ansel Adams" is on view August 21, 2005 - December 31, 2005 at The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Photographs by Ansel Adams. Used with permission of the Trustees of The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. All Rights Reserved.