Back in the heady early days of feminism’s second wave, the movement’s theorists poured forth torrents of words about the male monopoly on public power — economic, political, religious, cultural. If you had grown up in a world where the politicians, doctors, lawyers, novelists, scientists, artists, ministers, bankers and entrepreneurs were overwhelmingly male and where such aspirations on the part of a girl were not only against all odds but officially (by the reigning Freudians) ruled unnatural, these scalding exposés and analyses couldn’t help but strike a chord, especially at first. They gave a name — Patriarchy, rule of the fathers — to the wall of maleness that loomed all around you in the public world and the near-exclusive femininity it walled into the soft home-heart of that world. Before that, you wouldn’t have been able to find words for it. It was just the way things were.

Soon, though, as the wall was breached and women began to pour into the public world, feminist tracts became, to many of us, increasingly strident, doctrinaire and tiresome. There was still resistance, there were still barriers, inequities, prejudices, condescension, but the focus shifted to proving ourselves, which we were now free to do, with an optimistic sense that merit and resolve would prevail. And we have — with remarkable rapidity considering the weight of millennia on the other side of the scale. Some areas of culture still remain tougher than others for a woman to break into and excel in. I’ve heard the art world is one of them.

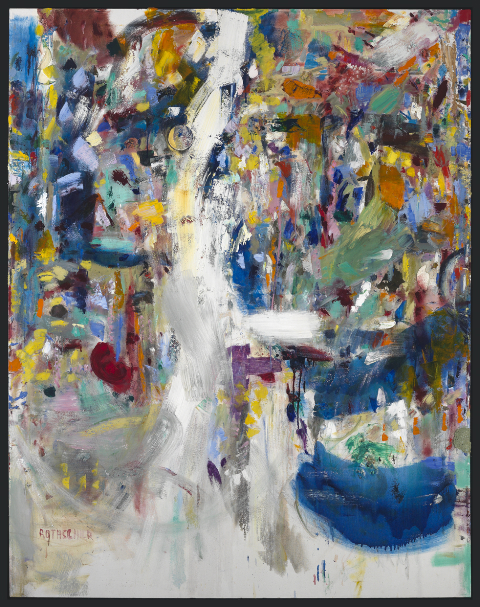

Boston, Massachusetts-based Jo Ann Rothschild is an ambitious abstract artist who often paints on a large scale. Jo Ann is also my oldest continuous friend. I moved to her street when we were both about four, and I still remember her throwing a hammer at the back fender of my bike as part of my initiation into the neighborhood. She was tough. I toughened up.

If I was a tomboy — climbing trees and catching spiders — what to call Jo Ann? When we played Roy Rogers and Dale Evans (*blush*), she was always Roy. When the boys played football, she was always devastated not to be allowed to play. She hated being dressed up in frilly girl clothes (although she later came to appreciate little black dresses) and saddled with the nickname “Missy” — bestowed to highlight the contrast with her older brother. Following stereotype you might deduce that she grew up to be a lesbian; you’d be wrong. She is the only female in her immediate family (husband, son), including the dog. She just thought the things the boys were doing, back then, were the really interesting things.

Like, art.

[At the Boston Museum School in the late 1970s] (Jo Ann writes), [a]n overwhelmingly male faculty taught an overwhelmingly female student body. The chief Boston art critic Ken Baker wrote almost exclusively about male artists. When he wrote about women artists his tone seemed snide. As a trial lawyer’s daughter I began to document, in a statistical way, the gender bias of the Boston art scene. In 1982 Art New England published my findings. They had to be edited because I was so shocked and angry. This created a little space for me. Not the publishing of the stats but my discovery that this is the world I live in, work in. This is what I’m dealing with.

I remember Baker’s calling one of my MFA classmates, Ralph Helmick, a “genius.” I had a show at Helen Shlein’s gallery around the same time and couldn’t even get a negative review. The ICA had an exhibition of Boston Artists that had only men.

Jo Ann could have remained “shocked and angry;” allowed bitterness to wither her work or turn it polemical; she could have blamed The Patriarchy for all her career disappointments. However, unlike some of the theorists I’ve called to mind above, she had… a sense of humor.

Sometime after [the all-male ICA show], I had the thought that the penis, this is the difference…

I thought about that until it seemed funny.

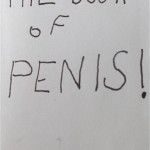

And so Jo Ann began to pen my favorite feminist tract, THE BOOK OF PENIS!

I have loved this little book from the moment I saw it and have held on to a battered Xerox copy for many years, but now at last it’s in print, thanks to micropublisher Pressed Wafer and Small Press Distribution (SPD). Why do I love it? Because it’s funny. Because it says everything that needs saying about the other P-word in almost no words at all. Because the vulnerable hand-drawn line and iconic shape almost make the work’s satirical edge caressing instead of cutting. Because it is so absurd (an all but one-gendered public world was absurd!) that it finally becomes endearing.

I am sure some of my readers will be offended by this little book and by my love for it. How would you feel, they’ll say, if the types and roles of women were caricatured by cartoons of your genitalia? (I think it actually has been done, but with less class.) How is this a constructive contribution to relations between the sexes? Aren’t the religion parts downright blasphemous? Isn’t this trying to rekindle a war that’s over?

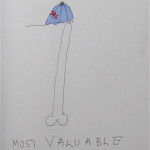

To them I can only say: please, try not to be as touchy and humorless as some feminists can be. (Note also that the book’s publisher, and the eminent museum curator who calls it a “little masterpiece” in his afterword, are male.) Indeed, this is a salvo in a battle that’s won in principle, if not yet over (and that could still be lost in many parts of the world, like Afghanistan). Indeed, Rothschild’s drawing of a phallic “Saturday Night Special” is aimed at a target that for us is largely in the past: at the likes of Norman Mailer, who, in Ancient Evenings, asserted that “the Egyptian word medu… means both word and stick (or penis)” and equated “speech and storytelling… with male ejaculation.” Mailer was certainly one of those who qualified, by his own hand, for my old friend’s most piquant distinction: “MOST VALUABLE PENIS.” (pictured below)

- Jo Ann Rothschild , After Chicago, oil on canvas, 2009.

- THE BOOK OF PENIS!, cover.

- “MOST VALUABLE PENIS” illustration from THE BOOK OF PENIS! A distinction Norman Mailer may have, by his own hand, made for himself.

Small Press Distribution (SPD) - The Book of Penis

All images are courtesy of the author and the artist.