As part of a continuing series proposing an interpretation of 'Synthetic Art', this issue presents a conversation between gallerist/curator Karine Jouenne and artists Reese Inman and Brian Knep.

---

Synthetic: Relating to or involving synthesis. Synthesis: the composition or combination of parts or elements so as to form a whole / the combining of often diverse conceptions into a coherent whole – also: the complex so formed (Merriam-Webster Unabridged Dictionary).

---

The Synthetic Art proposition references the synthesis of computer programming with digital and/or more traditional artmaking processes and techniques. The proposition does not advance a specific aesthetic, but rather offers a name and a concept to describe and provoke discussion around new hybrid artworks which are not represented well by existing formulations.

RI: Karine, how did you arrive at the Synthetic Art proposition?

KJ: I became a gallery owner/director/curator in the spirit of the explorer, simultaneously experiencing and interrogating. At first I surveyed Boston-based mid-career artists, and quickly began asking “what now? What is happening in artmaking that speaks to our evermore complex, multicultural, multi-dimensional society? What can contemporary art contribute to the socio-political discourse in response to such flatliners as the good versus evil school of thought? Can the aesthetic and conceptual dialogue evolve beyond a dualistic frame of reference?”

The resurgence of drawing and its recent permutations have been of great interest to me, but in much of the other work I was seeing, the lingering of aesthetics and strategies already extensively explored was disappointing, so I turned my attention to digital and technological art. However, the use of commercial software, mainly Photoshop, as an aid to artmaking wasn't quite providing the substantive breakthrough I was looking for, and self-styled “technological” artists haven’t won me over.

My initial eureka moment was probably seeing and experiencing Brian Knep’s interactive digital organisms. William Betts’ approach to painting via code writing for mechanical application, as well as your algorithmic paintings led me to the "synthetic art" thought. As I submitted bits and pieces of the proposition to you and we engaged in a dense conversation, our dialogue aided with filling in areas that I had previously intuited but not been able to formulate coherently. In a nutshell, that’s how it came about.

KJ: I am curious to know what circumstances and/or thought processes led artists to integrate computer programming and art making.

RI: I worked as a computer programmer - mainly multimedia work - for about ten years before completing the School of the Museum of Fine Arts Diploma and Fifth Year degrees. A couple years ago, I realized that my paintings were engaging issues and ideas from my experiences as a programmer. My creative process tends to be intuitive, so often the entry of new content into the work precedes my understanding of exactly where it's coming from. Upon realizing the relationship of the paintings to the computer, I became interested in making the conversation more literal, and started writing programs with the goal of creating dialogue between the computer and painting, or more specifically, between a computer algorithm that generates the cartoon for a painting - thereby giving the computer control over compositional decisions - and my hand, following the cartoon. The inevitable errors and inconsistencies of my hand as I follow the computer's output are a key aspect of the work, in combination with its computer origins.

Seeing the Ken Feingold show at SMFA last fall inspired me to push the idea of dialogue further, the idea of giving the algorithm a personality; while my early algorithms draw on how computers store and represent information, the more recent algorithms explore different attitudes toward travel within the world of the painting, e.g. liking to live on the edge vs. preferring the safety of the center. The paintings literally map the algorithm’s movement within the area of the painting.

BK: Although trained in mathematics and computer science, I've always had a love/hate relationship with the latest technology. Its seemingly limitless potential is exciting and tempting, but time spent creating and using these products often leaves me feeling disjointed and disconnected from my environment, my neighbors and myself.

I began studying pottery as an antidote to these feelings. The difference is remarkable, easily felt yet difficult to describe. Clay is physical and unpredictable. The connection between thought and product is direct and allows more of the unconscious, unfiltered thoughts and ideas to emerge in the work. Somehow the work has more of what I call 'soul'. Yet I continue to be drawn to the computer and it's potential, and so I began exploring this idea of 'soul' and whether it would be possible to create digital works with as much soul as the pots I have made and the pots of others that I have enjoyed.

KJ: Which artworks and/or technologies have inspired or influenced your work?

RI: Artists such as Sol LeWitt and James Siena, making rule-based work, and in LeWitt's case, also exploring the possibilities of delegating a portion of artistic control, are vital art historical ancestors for me. More loosely, Tom Friedman, Fred Tomaselli and Matthew Ritchie have all had a profound impact on how I think about constructing meaning. The work of Jason Salavon and as I mentioned earlier, Ken Feingold has been important. And then personal experiences with computer programming and technology have clearly played a major role.

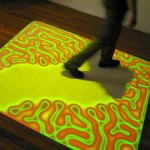

BK: I've been influenced by the body-based work of Myron Krueger and, more recently, Scott Snibbe. Work that directly engages the human body and requires human interaction. I feel drawn to large-scale, atmospheric installations like Olafur Eliasson's Weather Project at Tate Modern and great historic public spaces, such as the Duomo in Florence and the Blue Mosque in Istanbul. Places where people can share a transformative experience with others. To keep my work grounded I've looked to the work of potters, in particular the Japanese Mingei movement led by Shoji Hamada. He once said that rather than skimming across the surface of a stream, artists should stay in one spot and dig deep. I've also been heavily influenced by the work of mathematicians and biologists studying pattern growth. Alan Turing began the first explorations in this area and my work is often based on that of Aric Hagberg at Los Alamos National Labs.

KJ: Are there misperceptions or misconceptions about your work that you would like to shed?

BK: There's often a misconception that computers are infinitely programmable and can do anything one wants; that as artists, once we envision a work we simply tell the computer to do it; that the dialogue is one way. This is not true. Much like traditional artwork, computer art is constrained by time, money, the capabilities of the tools, and our own abilities. Programming languages and computer architectures influence and constrain the types of works we can do. There is a dialogue between the artist and the computer, and I believe that the more open we are as artists to this dialogue, the better our works will be.

A misperception is that the computer *is* the art. Computers are tools and, like any 'new' technology of the past, we have to learn how best to use them. Much as earlier painters had to learn to grind minerals and mix them with oils to make paint, I and other artists have to learn to program, wire, and solder to make our work.

RI: In a general sense I've experienced misperception of my work from both painting and digital purists. From the painting side, I've been accused of being gimmicky, from the digital side I've been told that if I really want to push the envelope, the work shouldn't take the form of a painting, it should be completely electronic. Such thinking seems odd, because painting is such an ancient and widespread practice, like writing, and I've never heard anyone suggest that writing can't be used to express whatever one might want to say about anything. I believe that the extensive history of painting practices and concerns provides a particularly rich ground against or within which the computer can operate.

Meanwhile, the very core of the work is a conversation between the hand and the computer, a representation of and reflection on the blurred boundaries commonly experienced in daily life, like when you call tech support and encounter a mix of phone system and human. Even if you end up talking to a live person, you're really interacting with a human-computer hybrid, because they're entering data into a computer the entire time you're talking, and if the network is slow, everyone has to wait until the computer lets you move on! Since we live in an era when hybrid human-computer experiences are the norm, purist or essentialist attitudes seem myopic and outdated, but I'm optimistic that we're gradually moving beyond that kind of thinking.

Links:

The Synthetic Art Proposition by Karine Jouenne and Reese Inman, Big RED issue #23

Synthetic Art: Genesis by Karine Jouenne and Reese Inman, Big RED issue #24

Synthetic Art: Perspective I by Karine Jouenne and Reese Inman, Big RED issue #25

Synthetic Art: Perspective II by Karine Jouenne and Reese Inman, Big RED issue #26

NAO Gallery

Brian Knep - blep.com

Seven Questions With Brian Knep by Matthew Nash, Big RED Article Issue #15

Images are courtesy of the artists.

- Scott Snibbe, Deep Walls, interactive video installation, 2003.

- Brian Knep, Healing Series, 2003-4.

- Reese Inman, Network I, acrylic on panel, 2005.