I went to see work by Natalie Loveless and Christopher Gardner, winners of the Bromfield Art Gallery’s 2004 SOLO Competition (selected by MIT’s List Center’s Bill Arning), late Saturday afternoon, as the first flakes of the gleefully predicted Nor’easter were falling. While I was in the gallery, dusk descended, and two inches of snow accumulated. As I was riding home on the T, I saw an ad on the subway for a Christian young life network, RealLifeBoston.com. It bore an appropriated comment from Leo Tolstoy, “is there any meaning in my life which will not be annihilated by the inevitability of death which awaits me?”

RealLifeBoston.com proposes to fill the existential angst of mortality with the enduring existence of a being with a benevolent plan for mortality. In the freshly blanked landscape of the blizzard and the weekend nighttime, it occurred to me that both Loveless and Gardner propose to focus on something else enduring – the infrastructure of flickers, lights, and signals constructed by humanity. Both sets of work explicitly record and manipulate life in the absence of mortal flesh.

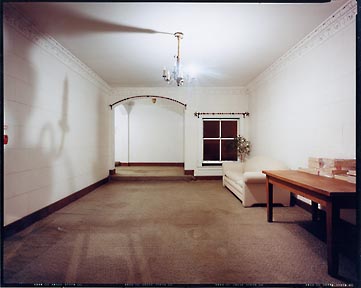

Christopher Gardner’s work, exhibited in Gallery II at the Bromfield, is a set of four gorgeous, large-scale photographs of the entryways of apartments in San Francisco’s Nob Hill. They are technically, formally perfect. The camera’s focus is even, but not the kind of anally precise focus that seems to correct human vision. The lobbies are shown in big, raked perspective. There are no people, no hint of movement, and the only traces of people (a note taped to a staircase addressed to “tenants,” for example) are so perfectly placed in the photograph’s composition that it feels like the exposure time must have been over a period of not minutes but years. The photographs’ subject matter becomes the luminescence of objects.

One stunning photograph, Clay 1455, shows a lobby lit by a single bulb from a chandelier. The one channel light source throws an amazingly specific, spindly shadow of its arms against the sidewall. The shape is writ huge and acts as a stand-in for the life that might teem there from time to time. Meanwhile, on the facing wall, a generic table holds a thick stack of telephone directories, encased in plastic. Fittingly, they are unbroken, unread. Gardner calls his work non-objective. It is true. They are neither subjective nor objective; they are to be looked at on their own time.

By contrast, Loveless’s brilliant installation is composed by a massive accumulation of specificities as dealt to her by instant messaging, at her handle bromfield_co_operation. As she wrote on her blog, “basically, I am fasting and isolated in the gallery, having conversations and translating them into graphs. These are mapped directly on the gallery walls, in silverpoint.” For five days, Loveless’s only source of communication and information was by digital technologies. She posted an invitation on rhizome.org, turbulence.org, and ikatun.com and asked anyone who surfed in to share their stories of mourning, memory or memorials. She then transferred those communications to the gallery walls by means of a system that is derived from the spatial relationships of the computer keyboard that mediated the received (and sent) messages.

In the resulting installation, a scroll of transparent plastic, tacked up in a corner, carried fragments of the instant messaged text of memories of loss. A number of the short reminiscences (timed out and word counted in one of Loveless’s many accompanying documents) rhetorically asked if their memories of dead persons were memories of a person who had never been realized for another living being—accounts of a roommate’s memories of the crazy, fun-loving art student whose parents probably knew and loved him as a stand-up, quiet boy. Others talked about the recent tsunami and the layered possibilities for loss. Others, about long sicknesses and losses that were easily metabolized.

In the end, though, all these personas and carriers of lost specificities turn frequent and standardized. Loveless’s wall-drawings are arranged at an even rhythm on the gallery walls from knee to head height. Their silver lines had a physical presence that reminds of filaments, fiber optics, and the three-dimensional aspects of cyber-functioning. Silverpoint is the very definition of objective line. It does not smudge, only tarnishes. Each instant message composed a system of self-regulating lines. Each was of even density and fairly equal size; someone’s two hand spans. Loveless had employed masking tape to mark out the parameters of the graphing system. There were blanks in the network of lines, and ripped out plaster, where the tape had been removed. I felt a phantom creepiness like player pianos in these absent marks; phantom fingers making present art.

Are you there – anywhere? It’s me, the artist. Just working with what is given, and what has gone away. Both Gardner and Loveless’s art, like instant messaging, work by presence detection. One click of the shutter, though, or one pinkie to the return key, and the mortal disappears. The work by the winners of the 2004 SOLO Competition is not the kidding kind, thank [all kinds of]god.

Links:

Bromfield Art Gallery

Natalie Loveless

Christopher Gardner

RealLifeBoston.com

"Natalie Loveless: Co(operation) and Christopher Gardner: Lobbies" is on view until January 29th at Bromfield Art Gallery, located at 450 Harrison Ave., Boston.

All images are courtesy of the artists and Bromfield Art Gallery.

Anneka Lenssen Anneka Lenssen is a Cambridge-based critic and a regular contributor to Big, RED, and Shiny.