To make an exact image is to insure against disappearance, to cannibalize life until it is safely and permanently a specular image, a ghost. (Haraway 1992)

The twentieth century is, in the words of Walter Benjamin, characterized by "the desire…to bring things ‘closer’ spatially and humanly…overcoming the uniqueness of every reality by accepting its reproduction." (Rony 1996)

The gallery at Suffolk’s New England School of Art & Design features the recent work of Sarina Khan Reddy, consisting of a series of photographs entitled “Picture Spot” and a three channel video entitled “The Great Game: A New World Order”

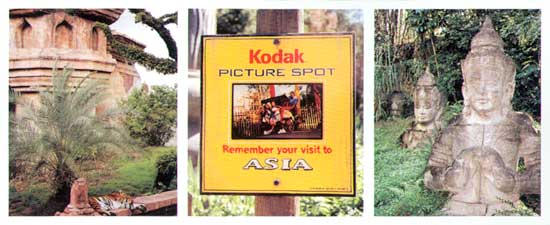

At first glance, the luscious c-prints in the series ‘Picture Spot’ are typical tourist photos of South Asia. Decaying Buddha sculptures nestled in lush green fern, temples in ruins surrounded by palms, a sleeping Bengal tiger, and rusted sign posts. But then, we notice --a pasty white arm waving from a plastic paddle boat, a handicap accessible symbol on a rickshaw, a McDonald’s French fry container crudely painted on a stucco wall- and the scenes begins to morph disturbingly before our eyes. These small clues hint to the crisis of representation that the series explores. It becomes clear that we are looking at a simulacrum of ‘exotic’ Asia, a life-sized diorama, inscribed with colonialist quaintness into which we can enter without passports and malaria medication. We are looking at a re-creation of something that exists primarily in the fantasies of the Western tourist. Sarina Reddy Khan has very subtly explored a very un-subtle environment, searching it for clues to Western notions of exotica and otherness. She perceives and then amplifies the fissures in an almost seamless creation of a picturesque third world landscape, otherwise known as the Asia section of Disney World’s Animal Kingdom.

Some of the most interesting breakdowns in representation occur, not surprisingly, at the boundaries of the theme park. This is notable as Disney has attempted to create a generic and boundary-less Asia here, one steeped in defunct colonial ‘charm’ yet entirely a-political. Disney has created for the visitor’s pleasure the mythical land of Anandapur. The crumbling architectural references to be found here (or the references to crumbling architecture) are a bizarre amalgam of Indian, Nepalese, Indonesian, Cambodian and Thai elements, creating something possible only in Disney World, but potentially for many, as close to Asia as they may ever come. In one photo, we see one of these boundaries, literally, the end of Asia. A wall of woven reeds abruptly ends, meeting a brick wall. The transition from one space to another amplifies the constructedness of both. It looks as though we’ve wandered into the stock room of Pier 1 Imports. It is inside these violent fissures in the faÁade Khan Reddy’s work invites us to enter. The most striking of these ruptures is a photo of one of the back exits of the park. A large metal gate, with the sign ‘Asia Gate’ and below that, ‘Evacuation, Plan B’ illustrates the profound disconnect that permeates this space. It appears to present an escape route if one is overwhelmed with otherness. ‘Plan B’- recalls an abortive measure, taken against the unknown. Disney has created the third world that was always attempted by Imperialism- climate controlled, easily escaped, conveniently free of ‘natives’ and catered by McDonald’s. By focusing us on these ruptures, Reddy Khan invites us to examine all the photos very carefully to tease out the failures of illusion, and the assumptions implicit in the set itself.

A conceptual thread throughout the photos is the way in which colonialist discourse is woven into and aestheticized by the experience. The photos illustrate “…the romantic ideology in which contradictory feelings towards other cultures are resolved by transforming them into aesthetic phenomena and in so doing decontextualizing and distancing them.” (Street, 1991) Even the choice of the wording on the signage tells us much. On one sign, carefully rusted and antiqued, is written, “Please respecting our temple area”. In imagining Disney’s research team, one can only wonder how this language was chosen. As Janet Wasko wrote in Understanding Disney, “The tone of a Disney nature film is nearly always patronizing.” Whatever the reasons for choosing this language, it ultimately infantilizes the writer and subsequently the sentiment expressed. But the glaringly obvious use of colonialist language and the implicit endorsement of an imperialist discourse comes later in the series. We see on another sign, “By special royal commission from the crown we have been granted the rights to serve french fried potatoes from the famous McDonald’s Restaurant. In the capital city, and here at Sundulo Toan (Golden Arches), these delights can be found. I beg you to enjoy them please.” There is so much wrong with this, it’s staggering. It implies that Anandapur is still under British rule and that a French fry is some kind of right to be granted (and it implies that McDonald’s is a restaurant, but that’s another issue). Apparently however, the creators of this exotic land have given it a ficticious history as well. According to Disney, Anandapur was established in 1544 as a royal hunting preserve.

Khan Reddy’s photos throw all of these meaningful fissures into stark relief. We are encouraged to scrutinize the photos for all kinds of meaning. The photos, at first glance gorgeous c-prints, become very edgy when we realize what is being photographed. And in capturing these scenes that are in themselves fictional, we are asked to question the very act of ‘capturing’ imagery photographically. Photography has often been used in anthropology as a tool of colonialism, and the photographic archive has been used to catalogue ‘others’ such as ‘natives’, criminals and the insane, since it’s inception. In fact, the lack of human subjects, but their implicit presence in this park, renders these scenes all the more creepy, giving the impression that no life can survive Western tourism. We are left with the notion that when we are done ‘capturing’ experience, when we have had all of our Kodak moments, no image can possibly remain. And in the safari theme parks of Disney, visitors can capture at will. “However hazy our awareness of this fantasy, it is named without subtlety whenever we talk about ‘loading’ and ‘aiming’ and camera, about ‘shooting’ a film.” (Sontag 1973)

Part of what is so disturbing about Disney’s version of Asia, is that it purports authenticity, but has in fact been deeply Disneyfied, a violent filter through which not much ‘authenticity’ survives. As Colin Sparks writes, “Disney transforms the products it acquires, not into global products, but into American products. It is American products that it sells around the world.” (Sparks, 2001) As we know from Aladdin and Pocahontas, Disney is a staggeringly powerful cultural force in the ‘business’ of representation.

Reddy has created a photographic archive of her own of this deeply problematic space, pointing us to the contradictions and the ruptures, causing us to ask deeper questions about the politics of representation. Perhaps the most emblematic image of the series presents us with the hoards of visitors, waiting to get out of the parking lot, which looks like an airfield, and into the park. They will be bussed in, group by group, and left to spend the day in Asia, Africa, as well as the Kingdom, capturing Disney’s world on film.

----

Links:

Gallery at New England School of Design at Suffolk University

"Sarina Khan: Recent Work" is on view at the Gallery at New England School of Design at Suffolk University located at 75 Arlington St., Boston.

All images are courtesy of the artist and the Gallery NESAD.

Jessica Poser is an artist, educator, and doctoral candidate at Harvard University. Jessica is a regular to Big, Red & Shiny.