This review came about as a sort of extended response to Charles Giuliano’s Jan. 9 comments re: Daniel Dueck and Lily van der Stokker at Allston Skirt Gallery. With characteristic frankness, Charles writes:

“Once again Allston Skirt presents a tandem of shows that focus on youth, whimsy and funkiness. Dueck is doing something about birds and van der Stokker is making scratchy little drawings with text. Other folks, whom I respect, appear to support and admire the work. It is getting serious critical and curatorial attention but I just feel out of the loop. What is it that I don’t get? Have I grown too old for whimsy? This work just seems too art school for me. Where do these ideas come from and what is sustaining them? When do we outgrow this and start getting serious? Or am I just getting to be ever more the curmudgeon?”

Reading these questions, I shared the sense of having more questions than answers. While I recognize this work as part of the larger postmodern project of repatriating the castoffs of Modernism, beyond that I feel kind of lost.

Surfing for clues, I checked out what various gallerists and curators who are showing this work have to say. Of what I read on the subject, the Decordova Museum’s introduction to their current group exhibit “Pretty Sweet: The Sentimental Image in Contemporary Art” made the most sense to me; the curators summarize:

“Contemporary artists approach the sentimental for three primary reasons: to celebrate the positive emotional spectrum, to evoke memory and nostalgia, and to ironically attack sentimentality as an inauthentic and damaging simplification of the human condition. Running through these categories is a deep ambivalence about the sentimental image, which parallels American society’s love-hate relationship with this material. On the one hand, the sentimental has been ruthlessly cast out of serious intellectual discourse since the early nineteenth century (most vehemently by Modernism), but on the other, the most successful artist working today is Thomas Kinkade, a painter of treacly landscapes whose art empire is traded on the New York Stock Exchange.”

The ambivalence issue rings a bell. In Venus in Exile (2001), Wendy Steiner ties the rejection of the sentimental in art to Kant’s influential division between the aesthetics of the sublime (masculine, awe-inspiring) vs. the beautiful (feminine, decorative, sentimental), and traces the history of excluding the beautiful from art throughout the past two centuries. As for irony, a decade earlier Thomas McEvilley’s The Exile’s Return: Toward a Redefinition of Painting for the Post-Modern Era (1993), characterizes painting of the 1980s as having returned from its much-heralded “death” at the end of Modernism with reformed manners, adopting a variety of strategies to avoid potentially contaminatory associations with Modernism. One such strategy is the incorporation of a twist of irony, offering up a compensatory red pill of critique, transformation or resignification – the use of familiar imagery in concert with an attempt to subvert the viewer’s prior associations. In other words, nothing is as it just seems at first. You have to read the fine print. This strategy has been, and continues to be, a vital feature of much postmodern artwork.

Lily van der Stokker’s work fits well within this frame. A Dutch artist who began to receive international attention in the early 90s, van der Stokker’s meticulous, colorful works on paper are studies for large-scale, site-specific wall paintings that frequently incorporate pieces of furniture or boxes built out from the wall. Her first solo museum project in the United States is currently on view at the Worcester Art Museum. These small works share an overall greeting card aesthetic, while their precision leans away from a craft or handmade feeling. Penciled comments such as “no progress” and lists of tea prices both personalize the drawings and offer a counterpoint to their lively line and cheery color, so here’s the twist, a gesture within the artwork firmly separating it from unadulterated greeting-card-ness.

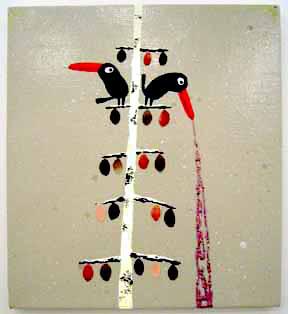

Daniel Dueck’s birds, sans obvious artsy twist or social critique, take a different approach – what you see is what you get. His deadpan bird images are fun to look at, offering the emotional and visual seductions of humor, bright color and glitter, while completely denying my art junkie’s desire for a twist. There’s an interesting textural play between Dueck’s matte grounds, crunchy reflective streams of glitter, and the deliberately simple brushstrokes with which the birds are rendered. Pleasure is neither denied nor deconstructed, and there’s something refreshing in the straightforwardness of the experience.

Perhaps this directness, the absence of critique, transformation or resignification, is part of what has been puzzling me and other artists among my acquaintance. After all, about the only thing this motley coalition of the puzzled shares is the experience of engagement in the art scene for more than a decade – we’re at least old enough to remember experiencing the art of the early nineties. Conditioned by a lot of amazing art that drew strength from such strategies, we now anticipate provocation, or at least irony. When its bittersweet taste is nowhere to be found, we blink. At least until we get used to it.

Links:

Allston Skirt Gallery

"Lily van der Stokker and Daniel Dueck" is on view until January 29th at Allston Skirt Gallery, 450 Harrison Ave #65, Boston.

All images are courtesy of the artists, Allston Skirt Gallery, and Feature, Inc., NYC.