Yasumasa Morimura’s large, flower-adorned self-portrait as Frida Kahlo immediately confronts viewers to the ICA with the image they perhaps most expected to see in Made in Mexico. Not that anyone is expecting to see a young Japanese man in indigenous-Mexican drag, but there’s bound to be plenty of expectation that Frida will make an appearance. It doesn’t take long, however, for the complexities of this exhibition to defy expectations.

As viewers approach Morimura’s photographic staging of Kahlo’s identity, they will notice not only the (knock-off?) Louis Vuitton shawl around his shoulders and the suspiciously Asian-looking pink and red flowers in his hair, but also Morimura’s wary gaze that should set viewers on alert. On the other side of the wall from Morimura’s work is German artist Andreas Gursky’s equally large color photograph Untitled XIII (Mexico), 2002, a dizzyingly detailed landscape of trash bejeweled with the bright colors of abandoned tourist goods and consumer waste. Whether intended or not by this installation, the specter of Kahlo is simultaneously exalted, destabilized, and left on the trash heap in Made in Mexico. Bringing together a talented, international group of contemporary artists, as well as Mexico’s iconic visual traditions and their aesthetic subversions, curator Gilbert Vicario has organized an exhibition that intelligently reinvestigates notions of national identity in an era of globalism.

The first floor gallery features several large-format color photographs, in addition to Gursky’s work, that bear close attention. Gaining access to an elite world of decadence via her own birthright, Daniela Rossell’s Ricas y Famosas series evokes a baroque sensibility ultimately to reveal strange combinations of unease and casual eroticism in the private spaces of Mexico’s upper-class. Sharon Lockhart’s photographs of a masonry worker in the galleries at Mexico City’s National Museum of Anthropology speaks almost too literally to the confines of an indigenous national aesthetic, as the glass partitions meant to protect museum visitors from his work area slowly enclose the man in the realm of the pre-Columbian. Born and currently working in the United States, Lockhart herself can only be a museum visitor in this exchange. The elegant stillness and muted palette of this triptych, however, foreground the sleek modernism of the architectural space, and the man’s active visual engagement with viewers defies his relegation—by either his surroundings or Lockhart’s astute photographic eye—to the Mexican past.

Two sculptural works by Lebanese-born Mona Hatoum dominate the first floor gallery, but perhaps one might have been enough. Hatoum’s La juala mexicana dominates one corner of the room, accompanied by a short DVD El párajo de la suerte, yet the bright color of the oversize birdcage competes with the intense details of the nearby color photographs, and the chirping and agitated motions of the canary prognosticator distract from the silent, but conceptually vocal, impact of other works in the space. In the opposite corner, her Pom Pom City spreads beautifully across the floor, suggesting both the order and chaos of urban centers, as well as the textile traditions of Mexican culture and the elegant post-Minimalism of recent decades. Near Pom Pom City, Santiago Sierra’s nine-panel grid of photographs Estorbando en el periferico quietly and powerfully communicates the cacophony of daily life in modern Mexico City.

In the second floor galleries, Sebastián Romo’s Límite and Pedro Reyes’ Maquetas arquitectonicas are both elegant sculptural investigations of Mexico’s present and past architectural landscape. Romo creates a pristine white version of Mexico City out of descriptive phrases, some probably not so pristine, collected from friends, laborers, taxi drivers, and other social observers. Reyes’ mixed media installation assembles a range of tabletop sized abstract architectural forms with anthropological, scientific, and art historical clippings, and directs viewers to consider connections throughout this display with short, handwritten instructions. The back gallery on the second floor has been transformed into two viewing rooms for films by Anton Vidokle and Andrea Fraser. On the left, the lean geometries of the building slowly painted red in Vidokle’s work provides a gracefully controlled counterpoint to the cacophony of urban sound offered up in the soundtrack by Christian Manzutto; on the right, Fraser’s cross-cultural and transhistoric dialogue with filmmakers Sergei Eisenstein and Olivier Debroise features both a complicated narrative of peasant revolutions and iconic elements of the Mexican rural landscape.

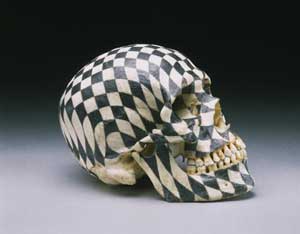

Upstairs, the viewer also encounters Gabriel Orozco’s 1997 Black Kites—a human skull delicately covered with a hand-drawn graphite checkerboard that shifts and stretches across the curving terrain of bone. This is a spectacular object, rife with the tensions between expected tropes and modernist defiance. In comprehending the role of Orozco’s work in Made in Mexico, viewers would be wise to keep in mind Morimura’s incarnation of Frida Kahlo directly below. Morimura has never been to Mexico, and has received Kahlo and Mexican art in general, as most of us have, through the lens of art history and popular culture. Orozco was born in Mexico, and while we may want to ascribe to his work our own assumptions about the importance of sugared confections offered during El día de muertos festivities, Orozco insists that we understand his work separate from a nationalist agenda, within an alternative context of psychoanalysis and Duchampian modernism.

Made in Mexico brings together an important range of artists working in Mexico, born in Mexico, and thinking about Mexico from abroad. In several places throughout the galleries the objects feel crowded, and the impact of their subtle critiques and reevaluations of Mexico’s aesthetic tradition gets lost in the distraction of other objects nearby. I suspect, though, that Vicario could easily have doubled the number of works in the exhibition, and the overcrowding of the galleries may be a testament to the potency of Vicario’s thesis (as well as the ICA’s need for that big new building they’re planning). Made in Mexico raises important questions about how any national identity is created, marketed, and received, and offers an impressive array of objects that respond to those questions in insightful and contradictory ways. Go see this show and rethink what you know about what it means to be made in Mexico.

"Made in Mexico" is on view at the ICA, Boston until May 9, 2004. It will then travel to the UCLA Hammer Museum, Los Angeles and be on view June 6 – September 12, 2004. An illustrated catalog accompanies the exhibition with an essay by curator Gilbert Vicario and interviews with the artists by Pamela Echeverría.

Image courtesy of the artist, Greene Naftail, New York & the ICA, Boston.

Rachael Arauz is a Boston-based independent curator who has worked at museums including the National Gallery of Art and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. She holds a Ph.D. in American and modern art from the University of Pennsylvania, and has organized exhibitions for the Williams College Museum of Art, the Davis Museum at Wellesley College, and, most recently, a solo show of drawings by Randall Sellers that will open at Miller Block Gallery in April [2004]. She is Associate Curator of 'Pattern Language: Clothing as Communicator', which will open at Art Interactive in Cambridge in August [2004], and is co-organizing an exhibition of the work of Keith Haring for 2005.

- Thomas Glassford, Aster Series, 2002–2003. Fluorescent lights, each aprox. 4 to 6 ft in diameter. Courtesy of the artist and Galeria OMR, Mexico City.

- Anton Vidokle, Stills from Nuevo, 2003. 16 mm film transferred to video, produced in collaboration with Sala Siqueiros. Courtesy of the artist.

- Gabriel Orozco, Black Kites, 1997. Collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art: Purchased with funds contributed by the Committee on Twentieth Century Art.