The role of language in visual art is frequently misunderstood. There are artists who do not see writing in their practice going much farther than their artist statement, a necessary evil. Likewise there are gallerists, critics, and historians who see writing as something outside the artist's purview. By and large such extreme opinions are regarded as outdated today, particularly in an academic city like Boston. Nonetheless, the effects of long-held prejudices and traditional divisions between the academic and the practical linger within the art world. But interaction with words and language is a fundamental part of living in society. History (as a practice) has perhaps exerted more influence over the lives of people through a process of both selective recording and forgetting. Even at the most basic level, the historical narratives that reach the level of general public awareness rarely encompass anything close to being comprehensive or even open-ended. Let us keep in mind that history is not just stories written in textbooks or documents stored in archives. We repeat the words of history in our every day lives. We use it to interpret our experiences and even our feelings from moment to moment. History tells us where we come from, what we are doing here, and helps us to imagine where we are going. But functionally, history describes things that no longer exist, so we rely on each other to a great extent in order to validate these thoughts and feelings. Intangible history is the ultimate not-being-what-it-is-about entity.

Adriana Sevila, Bajo el fregadero de cocina (I don't know how else to say this), poem, memorial with cement blocks, rosary, beads, candles

So, if the creative force behind art making is driven by lived experience, what are you to do if history has not provided you with words adequate for describing your experiences? Camaraderie provides fertile soil for cultivating more inclusive histories. Unity provides fortitude. Even within such sub-cultures, though, there can be chaos and disjunction. For ¡Qué Lástima!, a group of young Boston Latin@1 artists composed primarily of current students or recent graduates of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts and the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, their sentiments reflect diverse experiences that resists simple descriptions. Their May exhibition at MassArt's Godine Family Gallery highlighted the variety of perspectives among individuals who might be labeled Latin@, a label which writer, multimedia artist, and one of the founding members Ximena Izquierdo Ugaz described as "slippery." Another member, Bryan Rodriguez, suggested a more central question asking, "What does Latino mean? Do we all consider ourselves Latino?" Constructive criticism and reflection are important steps in the process of developing artworks, as much as they are in developing a life. This step is particularly emphasized on art students. The complexities that arise from questions like the ones posed above defy cultural-historical definition. Making art from this can feel like making gold out of lead if the environment does not cultivate honest discussions concerning those questions. We are used to viewing art about issues, questions, and stories. We are less accustomed to art that actually embodies its story in some way.

This fuzzy area where ideas meet realities is where the members of ¡Qué Lástima! make their work. "Instead of understanding what Latina means, it is giving meaning to Latina with our own lives," said Izquierdo Ugaz. The group does not keep a regular meeting location, instead they meet in each other's homes, talk, show work, and share meals. "That intimacy is so important," said Rodriguez, whose art practice includes first-hand research, interviews, and 'take-away' objects like post cards. "There was a desire for friendship first," he added. When asked how the group meetings had affected his work, member Ian Deleón responded, saying, "more than work changing, it's been more of an identity process within me of connecting with historical roots, and how my roots are related to the roots of everybody in this group — and using a language that I've only used in really casual family contexts and applying it to my daily life." Deleón's work incorporates education and activism and has been most recently exhibited in a solo exhibition and residency at La Galería at Villa Victoria Center for the Arts in the South End.

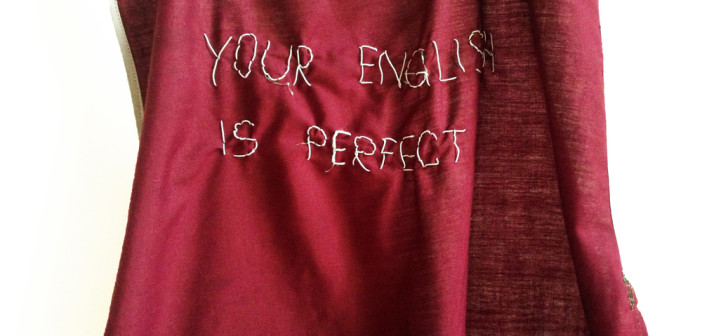

Ximena Izquierdo Ugaz, Wow, hand-made apron, threaded

¡Qué Lástima!, as a group, reflects the complexity within it. This is why it is not simple to define them as a collective, a crit group, or otherwise. Perhaps it is more relevant to describe what they do. The individual creation of words and tangible work out of this great complexity is made possible by a compassionate and respectful curiosity for each other and their lived experiences, by regarding moments of unity and conflict equally, and by nurturing the desire to make understanding from that. By seeking understanding amongst each other within the group their work is made not just about their lives. Rather, their lives actually manifest in their work. Artifacts of the past can be brought to the surface in the present. Speaking about their recent exhibition, Izquierdo Ugaz emphasized that it "shows the various directions we're coming from … there isn't one way of being Latino."

[1] If you're unfamiliar with this term, it has been described well in a post on the Reclaiming The Latina Tag tumblog: "The term Latin@ can be used simply to textually shorten writing in both 'latina and latino.' However, other people, particularly activists, may use the term for political reasons to promote gender equality/gender neutrality."

Their May exhibition at The Godine Family Gallery featured the work of Genesis Bàez, Sebastian De Gre, Ian Deleón, Oscar Cruz Díaz, Valeska Freire Marulanda, Risa Horn, Ximena Izquierdo Ugaz, Mario Lopez Pisani, Julia Pimes, Eduardo Restrepo, Bryan Rodriguez, and Adriana Sevila. The group plans to exhibit together again in the Fall.

¡Qué Lástima! can be reached for further information about their work and exhibitions via email at quelastimagrupo@gmail.com.

- Ximena Izquierdo Ugaz, Wow (detail), hand-made apron, threaded

- Ximena Izquierdo Ugaz, Wow, hand-made apron, threaded

- Mario Lopez Pisani, Monarquía en ojotas, oil on canvas

- Adriana Sevila, Bajo el fregadero de cocina (I don’t know how else to say this), poem, memorial with cement blocks, rosary, beads, candles

- Adriana Sevila, Bajo el fregadero de cocina (I don’t know how else to say this) (detail), poem, memorial with cement blocks, rosary, beads, candles