Believe it or not, An Enduring Vision was an exhibition catalog before it ever reached the Herb Ritts Gallery, published by the MFA in 2011. And it was part and parcel of a collection of some 6,000 photographs before being siphoned into its present state of just over 50 of those thousands. Yes, the newest exhibition on view at the Museum of Fine Arts cuts a broad swath with measured strokes. Used sparingly, each image has been selected for maximum impact. The are luminaries here, names you can’t miss, and objects that are iconic of entire aesthetic movements within the history of photography. And yet, something is still missing.

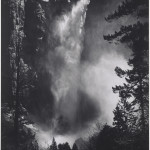

Bridal Veil Fall, Yosemite Valley, California

Bridal Veil Fall, Yosemite Valley, CaliforniaAnsel Adams (American, 1902—1984)

Negative date: about 1927

Photograph, gelatin silver print

*The Lane Collection

*Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The vision of the Lanes is certainly enduring. Renowned collectors Saundra Lane and late William Lane have been longtime benefactors of the museum. In an act of unparalleled generosity, Mrs. Lane gifted these photographs, along with 100 works of art on paper and 25 paintings, to the MFA in 2012. It’s a collection that includes numerous works by Edward Weston, Ansel Adams, and Charles Sheeler, and reaches across the history of photography from its days of romantic Pictorialism to its clear-sighted Modernism into abstractions, expressive or not, and the ill-defined contemporary. As part of that enduring vision, you will find Adams’ 1927 Bridal Veil Fall, Yosemite Valley, California hanging on the wall beside Carleton Watkins’ 1878-81 rendition On the Road to Yosemite Falls, New Topographics photographers Joe Deal and Robert Adams alongside street photographers Andre Kertesz, Paul Strand, and Jean-Eugene August Atget, or William A. Garnett’s aerial photograph Plowed Field, Arvin, California, 1951 next to Art Sinsabaugh’s 1961 panoramic Midwest Landscape #36. There are German cooling towers (but of course), Czech still lifes, Finnish self-portraits, and American nudes. Given the scope, you might expect to find a hodgepodge of an exhibition held together loosely by theme. But the arrangements within the gallery are visually clever.

Weston’s classically beautiful crab apple tree is immediately followed by Robert Adams’ more pointed parking lot tree under a crescent moon. Extending the critique, Mike Smith’s 1996 photograph of a veritable graveyard of ramshackle, deserted jalopies in the Bristol, Virginia woods comes next. Wright Morris’ Bed, Ed’s Place is paired with Ansel Adams’ White Gravestone, Kenro Izu’s sacred still life Ladakh #43, Praying Instruments, India, 1999 with Joseph Sudek’s tinfoil and tape concoction, simply titled Still Life, 1959. There is even a 1996 portrait of the Obamas in their Chicago living room by Ansel Adams’ last protege Mariana Cook.

In short, it’s a Who’s Who of photography and a comprehensive primer, aiming to impress and guaranteed to have something for everyone. But like all primers, the details can be lacking. The distinct art collecting strategies of Saundra and William Lane are everywhere evident in An Enduring Vision. The two made their lives together, but could not have acquired art more differently. While Mr. Lane collected the work of select artists in depth, his own personal favorites, the Mrs. had a more expansive approach. Stylistic movements and photographic processes interested her far more than individual artists. Less specialized, and more diverse, her tastes can be seen in the breadth of An Enduring Vision, from its 19th-century paper-and-glass-plate negative photography to its experimental abstraction. William Lane, by contrast, aimed for depth, amassing 2,500 of Charles Sheeler’s photographs alone. In that sense, An Enduring Vision has both depth and breadth, but, based on curatorial decisions, not necessarily much of either.

I’m a realist. I understand why a gift of this magnitude deserves an appropriate exhibition, one that pays homage to the eye, or vision, as it were, of the collector. It’s as much a political necessity as it is a heartfelt show of gratitude. You’d be naive to think the two were mutually exclusive. And there’s certainly no harm in bringing Modernist greats to the public. Whether you know a lot or a little about photography, you’re guaranteed to find a gem here with little digging. It’s that kind of exhibition, a user-friendly one with some surprising images.

But if you’re expecting to discover the real diversity that the medium can offer, then I’m afraid you will miss more than the contemporary photography that is a distinct weak point in An Enduring Vision. The overwhelming majority of the photographs on view date from the 1960s or earlier, and only five were made within the last twenty years. And those are hardly representative of recent developments or aesthetic shifts, even in the most rudimentary sense. But that is not what I personally find most troubling about the MFA’s newest exhibition. After all, you can take a stroll over to the adjacent contemporary wing, if that’s where your heart lies.

A collector, of course, is free to acquire whatever most pleases him or her. But a curator, who is an educator, after all, should have other considerations. It is a sorry state of affairs when an exhibition at a leading museum in 2013 features only eight women, and only one non-white artist (Japanese photographer Kenro Izu), out of over fifty photographers whose work is on view. It’s not that I do not appreciate the work of Francesca Woodman or Imogen Cunningham. I do, even the two photographs included in An Enduring Vision. But I confess that I was left wondering at the absence of work by artists like Julia Margaret Cameron, Anna Atkins, Berenice Abbott, Margaret Bourke-White, Dorothea Lange, or Helen Levitt, to name only a few. I should be clear. I am not criticizing anyone, the curator or otherwise, for leaving out these artists in particular. After all, I’m not certain whether any of their photographs are in the Lane Collection in the first place. But there are many, many women photographers of their stature, and I would expect to see more of their work taken seriously by the Museum of Fine Arts, especially in a historical survey of this kind. As for non-white photographers, perhaps the MFA could take a lesson from the Peabody Essex Museum’s recent exhibition In Conversation? Because there are huge gaps in An Enduring Vision that need addressing.

It’s an idiosyncratic exhibition, to say the least, and a selective history of photography. It has strengths and weaknesses that I can only presume originate with the collectors. In that sense, I suppose there is something personal and unique, and arguably touching, about An Enduring Vision. But, ultimately, I have to question some of the curatorial decisions. Because An Enduring Vision has great depth in certain areas, but is also woefully superficial in others; it has breadth, but is also painfully narrow. It is a primer indeed, but one written more like a diary.

- Susan Sontag and her son, David, N.Y.C Diane Arbus (American, 1923—1971) 1965 Photograph, gelatin silver print *The Lane Collection *Copyright © The Estate of Diane Arbus *Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Chambered Nautilus Edward Weston (American, 1886—1958) 1927 Photograph, gelatin silver print *The Lane Collection *Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Bridal Veil Fall, Yosemite Valley, California Ansel Adams (American, 1902—1984) Negative date: about 1927 Photograph, gelatin silver print *The Lane Collection *Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston