In October I visited Steve Hollinger’s studio at Fort Point and got a preview of the work now on view at Chase Gallery. The work was so mesmerizing that I left eagerly anticipating his show. His studio is like a cabinet of curiosities – antique and found objects line the shelves, and jars, bottles and boxes waiting to contain the precious objects lie scattered about. Hollinger combines these found elements with modern technology in solar powered sculptures that simultaneously juxtapose science and art, and reveal the nostalgia and naïveté of the atomic age and the anxieties that it created. The imagery is complex because it simultaneously repulses by referencing issues such as genetic engineering and atomic experimentation and attracts with precious jewel-like objects nestled inside wooden cases.

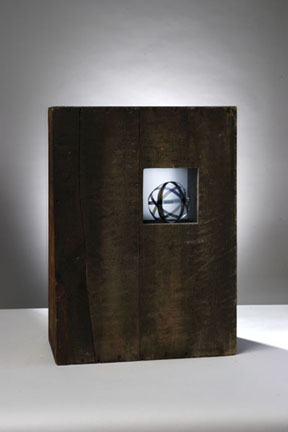

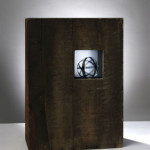

Hollinger’s kinetic sculpture is beautiful and mysterious. Removed from the studio and placed on spot lit pedestals in a cool white room the work is transformed from curiosity to objet d’art. Antique explosive boxes from the 1940s and 50s, branded down each side with the names of companies like Trojan Chemicals, Hercules Powder, Atlas Powder Co. and American Cyanamid and Chemical Corporation, hold the delicate fluttering forms of polarizing film. The objects hover in an illuminated niche and are sometimes contained in a vintage glass bottle affixed to the space. The film is woven into spherical shapes, or cut into broken assemblages of material. A second polarizing filter, hidden behind the frosted glass plate that lights the object, spins – creating the illusion of movement. The dramatic effect is difficult to describe in writing and must be experienced first hand, and the resulting imagery is both mesmerizing and enchanting.

While questioning the technical mechanization that creates this illusion is not the purpose of Hollinger’s work, it is interesting to explore the technique. Polarizing filters were invented during the Atomic Age by Edwin Land, founder of the Polaroid Company and were originally utilized for optical instruments because they respond to light. Today they can be found in sunglasses, window shades, and LCD displays. When two polarizing filters interact their tonalities shift on a spectrum from transparent to opaque, thus causing the effect of movement and change in color. By masking the process from the viewer Hollinger’s floating forms appear to morph by magic alone.

As the title of the show suggests, Hollinger draws on atomic imagery to inspire his work, though some pieces reference it more directly than others. For example, Atomic #2, and #3 recreate the simple beautiful motion of electrons revolving around a nucleus. Other imagery is less directly related to the atomic theme and references the effect of growth due to photosynthesis. In Elm and Main a bed of long strips of film mimic grass growing toward the light. As the filter behind the plate spins, the color of the film changes from dark sepia to eerie orange and purple - colors that are unnatural to plant life. Perhaps this microclimate suggests some environment altered by atomic energy? In addition, the use of glass bottles that resemble test tubes suggest anxiety about collecting and experimentation. Although the meaning is unclear, the format is beautiful. Hollinger notes that he was inspired by the place or story of a nuclear test site, but that the work reflects his experience with the research and does not specifically relate to that event. Instead, the titles reflect a sense of anxiety about human interaction with atomic energy, especially when paired with the more ambiguous and grotesque manipulations of film.

What about the boxes? Hollinger successfully juxtaposes his technologically savvy creations with age-old wooden boxes, evoking a sense of nostalgia for a bygone era when collectors crowded their shelves and walls with catalogued objects. Because the boxes held chemicals and explosives their new cargo is charged with their past history. They seem to ask: how has the atomic age influenced humanity today – from the smallest particles of life to the blades of grass that we take for granted?

The format of the largest piece, 25 Atoms, contrasts strongly with the smaller box sculptures. Illuminated from behind by a wall of light of equal size, a glass cabinet of 25 revolving atoms is sleek and modern – and it is breathtaking. Freed from a heftier wooden box, the design suggests the unencumbered future rather than nostalgia for the past. And the future is bright!

Links:

Chase Gallery

"Steve Hollinger: Atomic" is on view until December 30th at Chase Gallery, located at 129 Newbury St., Boston.

All images are courtesy of the artist and Chase Gallery.