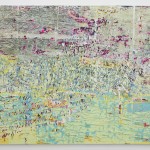

Mark Bradford

Mark BradfordFather, You Have Murdered Me

2012

102 x 144 inches

mixed media collage on canvas

Photograph courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Rules against touching the art always seem odd when you consider that most paintings and sculptures come to be through processes of constant and intense handling. One day a painting is in the hands of the artist, literally, and the next it's in a gallery or museum where it's off-limits to human touch. This must seem odd to Mark Bradford, too -- he ran his hand down the Rose Art Museum's "Father, You Have Murdered Me (2012)" not once but twice during his gallery talk at the Rose on March 19. "I don't own it, but I felt like touching it!" he exclaimed in mock horror the first time.

Bradford may not own the piece anymore, but the large, lightly-gridded, swirling abstract painting made of multicolored paper bits layered on then ripped or sanded off, is instantly recognizable as his work. In conversation with Rose Director Christopher Bedford, Bradford talked a lot about paper -- the "high-low" relationship of paint to collage, and the appeal for him in blurring the line between them; how his shift from using mostly posters and flyers scavenged from city streets, to using mostly custom-silkscreened paper, reflects the economic and cultural changes around his south LA studio (flyers are less abundant as more buildings/communities enforce no-posting rules); and how he came to use paper in the first place ("I was broke!" and it was readily available for free).

Speaking for a quick hour to a packed gallery, Bradford touched on lessons learned from his experiments with installation work at Miami-Basel and the post-Katrina Prospect 1 biennial in New Orleans, and said he never saw his social/community interest as separate from his art practice, as many artists do. His deep interest in micro economies is evident not only in the raw materials he uses in his abstract work, but also in his ongoing series of "merchant posters," heavily-altered street flyers advertising services that reveal the economic concerns and social issues of the communities they're found in.

Coming out of CalArts with an MFA in 1997, Bradford says he felt the most political thing he could do was to "be an African American painter," since painting was out of fashion at the time, and there was no tradition of black abstractionists. Setting himself apart from the Abstract Expressionists to which he's sometimes compared, Bradford talked about his conscious efforts to distance himself from any gestural marks in his work (one way is to trace them with twine) as a way to refute "that whole channeling thing from the 50s." Instead of exposing deep personal internal impulses, Bradford taps into the rhythms of people moving through public spaces, the grids of cities and neighborhoods, and pushes it all toward the abstract in his paintings.

Asked about his work with teens as part of a year-long audience engagement residency at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Bradford called on the art students in the room to "be at career day," and go into spaces that aren't "art-safe" and re-animate them with art. Going to community centers, after-school programs, etc, "you can reach those kids" who will be tomorrow's artists, but who may be outcasts today. "You gotta get with your own tribe," Bradford tells artists, and be a role model for kids who are like you, to show them they can make it.

Though he describes it as a "political strategy" developed in response to the "language of engagement" he was taught in art school and his own discomfort with "performing 'smart'" earlier in his career, Bradford's casual speaking style is as refreshing as his take on abstraction. That he seems genuinely hesitant to over-analyze his motivations and the messages in his work is all the more impressive since they're so densely packed and deeply integrated into it. "Your practice evolves to be like who and how you are," he says, and it really is evident that his work is both an extension and a reflection of himself and the place and time in which he's working.

- Courtesy of Rose Art Museum

- Courtesy of Rose Art Museum

- Courtesy of Rose Art Museum

- Mark Bradford Father, You Have Murdered Me 2012 102 x 144 inches mixed media collage on canvas Photograph courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co.

Mark Bradford's "Father, You Have Murdered Me (2012)" is on view in "On the matter of abstraction (figs. A & B)," at the Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University through June 9, 2013.