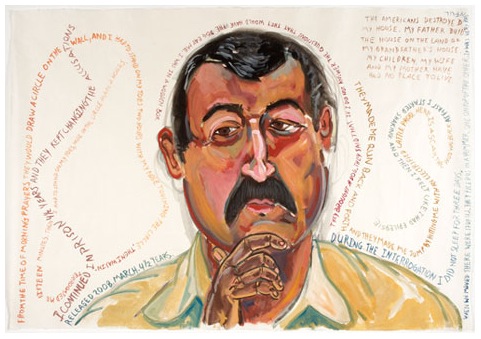

Do you remember Franz Kafka's drawing machine? It is the executioner's device of the story In the Penal Colony, where it punctures the text of the violated law onto a prisoner¹s body. In Daniel Heyman's images of Iraqis abused in the war's prisons, the testimonies of the tortured serpent across the paper, like tattoos of agony.

One such thread of words in the man¹s image entitled I Did Not Have a Beard reads "there is one other thing that happened...but I cannot talk about it". We know from his refusal that there is a text of unimaginable pain that is constantly before his eyes. Hamlet¹s murdered father makes his ghostly way from hell only to tell his son that he can say nothing of the torments he endures there, since the least of them "would harrow up thy soul." This is the tortured's quandary: how to narrate a story which is unbearable to both teller and audience, yet if it is not heard, future horrors are given license to multiply in the silence.

These are not the photographed screams with which bureaucrats cataloged the doomed in Cambodia's extermination camps. Looking at those, we hear our own anguish, not theirs. Heyman's renderings are portraits of both person and speech, like transcendent cartoons where the dialogue cannot be contained in the conventional balloons of conversation, but spills out, amok, with the color of the words shifting and vibrating like the tone of voice speaking them.

There is an unexpected paradox in the silk bound covers fashioned for the accordion albums of these faces, with such delicate splendor as a container for pain's history. And I thought of the philosopher Walter Benjamin's conviction that "There is no document of civilization that is not at the same time a document of barbarism," although here the contradiction is deliberate and critical.

A different model is applied in a series of a series of prints entitled Redacted Portfolio that is a joint project by Heyman and the poet Nick Flynn. Here the images evokeBen Shahn's furious clarity, with the text punctuated by omissions, censorship with a difference, meant to horrify with its absences. But their very incompleteness and flattened dimensions suggest a function as poignant footnotes to the full portraits, rather than as a story of their own.

In a smaller group of pictures, African-American men from Philadelphia are threaded to the Iraq portraits by the common experience of prison. Fewer details emerge in these narratives about the damage done to them there, yet enough is offered to connect the acceptance of the immense penal colony in our own country with the indifference to the torture chambers of Abu Ghraib. What was the training ground for them, if not the isolation chambers of penitentiaries here at home, those domestic illusions that we have found security?

In a recessed alcove at one end of the gallery, like the display of some newly excavated Babylonian city gate, is a plywood construction patterned with ink engravings. Here is a visual glossary of relics from the long violence in Iraq, inheriting the outraged profanity of Philip Guston and Robert Crumb. It is as if an iconostasis meant to veil the altar of an Orthodox church had been desecrated for the sake of the truth, with no doors into a sanctuary where forgiveness might wait.

The same morning I walked through Heyman's show, I learned that a friend, a painter, was dying. He, too, had been marked by our time's wars, and then had put those marks down on canvas. Those works have never been publicly shown. How many other artists, here and in Iraq, have taken these brutalities on without finding the conscientious venue that Heyman has? His work is for them, too, in their struggle to be heard above the clank and clatter of this rapacious thing we call our culture.

So I carried a private grief to one last face on the exhibition's walls. "I was released with no money very far from my house", read the words of a man for whom the term survivor would have no meaning, even though he goes on living. He will always be very far from that place he called home, except for the trace of it that Daniel Heyman has made for him in this bright memorial of his loss.

Daniel Henyman

Ezra and Cecile Zilkha Gallery, Wesleyan University

"Bearing Witness: Stories from the Front Lines" is on view through May 23rd at Cecile Zilkha Gallery in the Center for the Arts at Wesleyan University, located at 283 Washington Terrace, Middletown, CT.

All images are courtesy of the artist and Cecile Zilkha Gallery