A FEW APPARITIONS OF NATIONHOOD @ THE ALDRICH MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART

With its current suite of exhibitions by artists: Dave Cole, Alejandro Diaz, Robert Lazzarini, Frank Poor, Harry Shearer, and David Taylor, the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum has managed to create a rough conspectus of the collective identity of the United States in the present. What would have been both an immodest and unwieldy ambition as an announced intent is well served by the subtle elision of an overarching curatorial statement. Together, the works on view emerge as bilocated doubles forming an uncanny abridgment to the blustery political life of the nation.

As I roll into Ridgefield, CT ─ itself a becalming slice of the American Dream where loosely strung together cul-de-sac manses are occupied by affluent Manhattanites on their summer reprieve ─ there is little signifying that anything exceptional of a social nature, say nothing of intellectually stimulating contemporary art, might reside here. However, upon arrival at the Aldrich the edenic pretenses of pecunious suburban life are immediately brought into relief by Frank Poor’s Enon Cemetery.

Comprised of nearly two dozen wooden surrogate funerary monuments with familiar epitaphs and motifs fractured and skewed upon the surfaces like the text of a Stuart Davis painting; Poor’s cemetery is suggestive of both the immanence of the life cycle and the timeworn foreboding of et in arcadia ego while additionally serving as a means of positive disorientation toward the conventional representative signifiers of man in his gravest state. While Poor tends to abstract and therefore generalize the intent of the funerary marker he has also implicitly inscribed upon them: Here lies what you see is what you see; nothing more and nothing less. A few honest blanks lie amidst an artificial paradise.

Indoors, one first encounters Dave Cole’s Flags of the World (Study #3), 2008, a wall-hung American Flag composed of sewn together bits of fabric extracted from each of the 192 piece United Nations “Flags of the World” replete with a laundry cart of littered remainders below. Though itself a somewhat heavy-handed gesture; like any flag, Cole’s generally alludes to the much more differentiated innards of what it purports to represent. Its installation at the Aldrich sets the tone for many of the remaining exhibitions in that it seeks to define an entity by that which is external to it. This blurring of the dialectic of I/us and non-I/them is clearly present in both the antagonistic practice of Mexican/Texan artist Alejandro Diaz and David Taylor’s circumspect documentation of the U.S./Mexico border.

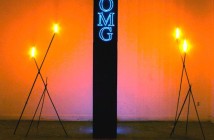

In Alejandro Diaz’ exhibition, Blame it on Mexico, fear and cultural unease are treated with a lighthearted approach as the artist employs humor to address xenophobia and ethnic stereotypes largely by means of what seems to be an almost hierarchical use of vernacular signage which in a few instances has been paired with conventional sculptural assemblage. Behind a ten by twelve foot sculpture proclaiming to be the World’s Largest Cardboard Sign, several smaller cardboard and neon signs bearing somewhat less than aphoristic slogans are cluttered through the galleries. Although many of the phrases writ upon the signs (I Can’t Remember the Alamo, Mexicans without Borders, or No Shoes, No Shirt, You’re Probably Rich) can neither claim to be particularly well-articulated or clever and are hence somewhat dissatisfying individually; the accumulated body of these messages on cardboard effectively speaks to the desperation, thrift, and casual making-do that one finds in the beggars plea, the day laborers self-advertisement, or the hastily scrawled notice informing you that the stall is out-of-order while simultaneously pointing toward the collective hopes, dreams, and vanities of the inhabitants of America in the 21st Century.

Additionally, Diaz has produced a schlocky checklist-cum-ballot extending to the viewer the opportunity to elect his or her favorite cardboard sign to the privilege of being inaugurated as a newly minted work in neon text; a medium once thought base now poised as the crowning achievement of indistinguishable contemporary art.

Complimentary yet to a large degree counter to the sweeping proclamations of the former is David Taylor’s Frontier/Frontera; an understated highlight amongst the current exhibitions. Taylor’s exhibition, made possible by the regular surveillance of U.S. borders, features documentary photographic and video based works recorded largely with the cooperation of the United States Border Patrol as he accompanies agents during their field operations. Inhabiting a space that is frequently referenced in abstract terms, Taylor presents the particulars of this heavily politicized territory in the unbiased manner of an entranced painter of modern life. Much like the patrol agent, Taylor’s documentation is wed to both working spaces of the occupation, the station and the frontier, and as such the viewer is allowed a glimpse into two distinct realms that they would typically lack access. Representing the former, we see amongst other images: a female agent seated at a desk within a homey office space, a camera room plastered with monitors as though compelled by some abhorrence of empty space, and a monastic detention cell with a neatly folded serape in the corner.

Perhaps most captivating within this series is Intell Info, TX, 2007, a photographic quodlibet of paperwork tacked upon a wood-paneled wall with items varying from a list of most wanted terrorists and a booklet stenciled with the words “Intell Info” to the printed protocol for the release of alien property and a promotional flyer containing portraits of a few of the Border Patrol’s celebrated scent-finding Retrievers, Shepherds and Belgian Malinois. However, it is the frontier that truly propels the work and it is in the frontier that Taylor is able to convey the breadth of social and even spiritual events that occur along this imagined division. In Taylor’s hands the border fence becomes an alluring if not bewitching object through which human activities from rural farming to urban street life are seen functioning up to the very margins of national territory. This sense of spillage is perhaps most evocatively captured in the several pieces that record the annual pilgrimage made in late October by mostly Catholics of Mexican ancestry to the sculptor Urbici Soler’s statue of Christ the King atop Mount Cristo Rey seated upon the international border and across the Rio Grande from El Paso in Sunland Park, New Mexico.

These pieces, including panoramic photographs and single channel video, collectively titled A Measure of Faith and a Line in the Sand exhibit the complex relations of two nations from a location that long served as an embodiment of cohabitation on an otherwise fortified southern border. Having been equally accessible from both U.S. and Mexico prior to 9/11, this boundary once routinely transgressed without impediment in processions of fervent spiritual devotion now lies cordoned off under the auspices of national security. However, this perceivable discord is denied any claim to prevalence. Through Taylor’s lens, the variegated social and political contentions of the region are eclipsed beneath Soler’s Cristo Rey as it stands aloft; an allegorical plateau beyond the physical and emotional lines that define nationhood.

Taken as a single entity, each individual perspective on view at the Aldrich has managed to work within the institution’s bantam proportions to contribute toward a potent image of the contemporary U.S. political landscape. That being said; it is in your best interest to retrieve your TurtleWax® and chamois from their long neglect. Check oil and coolant levels. Take leave and attend!

- David Taylor, Procession from A Measure of Faith and a Line in the Sand, Archival Inkjet Print on Dibond, 2008

- Alejandro Diaz, I Voted from Blame it on Mexico, cardboard and marker, 2008

- Frack Poor, detail from the installation of Enon Cemetery—Main Street Sculpture Project, 2009

For further information on the various shows currently on view at The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, visit the museum'sexhibitions page. The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum is located at 258 Main Street in Ridgefield, CT.

Images courtesy of the author, the artists, and The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum