CONNECTIONS @ MIT MUSEUM

The Connections exhibition by the Sociable Media Group at the MIT Museum is part research, part art –turning theories and data sets into interactive portraits and installations that explore recent technological developments in human communication. The group explores many common themes in art and culture today, and tries to address questions, including “How do social conventions develop in the networked world?” and, “How do we perceive other people online?” What’s interesting is that the projects are created as a means of scientific research, which obscures a dominant intention or point of view. The art that results is open, and allows the viewer’s personal engagement and reaction to play the biggest role in how each piece is interpreted.

A highly interactive portion of the exhibition is the installation entitled Metropath(ologies), which is essentially an environment created to simulate virtual reality. White pillars of varying heights are canvases for projected data and digital images. Haunting audio plays in the background, sometimes a digitized female voice reading headlines, data, and other text, other times the clamor of typing on a keyboard takes over, or adds to the confusion. Visitors even have the opportunity to add their own recorded voice to the soundtrack. As you walk through these white columns and become part of the environment, you arrive at a station with a video camera that captures you standing among the digitized world. Ghostly, cloudy figures of human forms fade in and out of view, comprised of illegible text and images. While this environment is meant to simulate our experience engaging with others online, you cannot help but feel strangely alone standing among these very non-human sights and sounds.

Another interactive component of Metropath(ologies) is a very unimposing computer that invites you to type your name into a simple search engine. Immediately, the computer retrieves a number of articles or web pages that contain your full name. Adjectives from these recovered web pages are strung together to give a digital snapshot of your personality. This entire practice makes the viewer highly self aware of time spent meticulously choreographing your Facebook profile to accurately portray yourself to the online world. The experience is fun, but also shows just how arbitrary digital snippets can be, which reveals the absurdity of basing any serious judgments on information gathered from Google or Facebook.

Moving through the exhibition, you are invited to sit at a roundtable to watch a TV screen embedded in a figure, standing in for a potential communication partner. The installation features a series of digital slides that depict potential projects, which would bridge the digital gap that exists in our current online communication. One screen expounds the physical and psychological facets of the game of poker, which are entirely negated in the popular online version of the game. The project would find a way to visually depict the player’s facial features and physical movements, bringing back the inherent psychological complexity of the game. Thinking of how rapidly technology has evolved in the last two years alone, it brings to light that many of these possibilities are not far off on the horizon, and that our digital world and online relationships could be expanded even further.

The various Data Portraits in the exhibition hit a surprising nerve, tapping into something that feels very personal and private. Themail pulls the most frequently used words from email correspondence between different individuals and arranges them on a free form chart. It’s fascinating and voyeuristic to peer into each relationship and follow its evolution over the years through text data. One piece portrays a romantic couple, Judith – Before and After Marriage. The text evolves from “pretty, sweet, baby, shopping, night” and other more carefree terms to more serious and career-oriented words such as “business, flight, software, companies, technology, and love.” The final months represented in the portrait are dominated by the names of children and terms such as “school, schedule and therapy.” The entire portrait is drawn out from 1991 through 2008, and simultaneously depicts the increasingly important role that technology plays in interpersonal and work relationships.

While new technology has brought us closer together in many ways, it is also changing the dynamics of our relationships. A few weeks ago, Niel Swidey published an article in Boston Globe Sunday Magazine about our constant digital connectedness entitled The End of Alone. In the article, he cites psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott who stated that our capacity to be alone is an important component of our social and emotional development. While technology has offers us new possibilities to engage with others, this generation is missing out on an important part of their own personal development. Similarly, our online world is inherently incomplete. From every individual who strives to remain a bit more mysterious by not registering a Facebook account, to many of our grandparents who don’t engage with the online world, the digital portraits we see in this exhibition are either left unfinished or cannot be composed at all.

What makes this exhibition more art than research is the fact that it resonates with the viewer on an emotional level. We are uncomfortably reminded of how personal and intimate our online activities can be, and how dramatically they have changed the way we live over the past few decades. Thoughts and conversations that were once private are now extremely public, and the result is a stark change in the way we perceive ourselves. Connections highlights the ways technology has broadened our virtual social network, but also raises questions about how it might be changing our reality.

- Installation shot of Metropath(ologies)

- Example of graphical data of one user in Mycrocosm

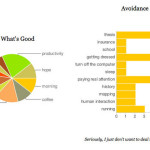

- From the Sociable Media Group’s webpage, showing one of the many examples of their other Data Portraits

Sociable Media Group

MIT Museum

"Connections" is on view in the The Mark Epstein Innovation Gallery at the MIT Museum, located at 265 Mass Ave., Cambridge, MA

All images are courtesy of the the Sociable Media Group and the MIT Museum.