When the Museum of Modern Art reopened in Manhattan, Eva Hesse’s sculptural assemblage of knee-high translucent rumpled cylinders, “Repetition Nineteen III” (1968), was installed behind a wall that held a large Agnes Martin painting. The pairing was apt: both women resisted the emotional desiccations of minimalism, and both found sublime and rhythmic expression through techniques that left traces of the artist’s hand. The positioning of Hesse’s work -- out of sight to viewers until moving past the Martin painting and peering around the wall -- was also apt: Hesse is like a darker, funkier Martin. Hesse’s sensibility taps into everything that generally stays hidden from the light of day: death, sex, existential agitation, and, in the words of the artist, “the total absurdity of life!” No wonder MoMA placed her work behind a wall. But this summer, Hesse’s pervasive and palpable ghost emerges in two excellent Manhattan exhibitions: Eva Hesse: Sculpture at The Jewish Museum (May 12 - September 17), and Eva Hesse Drawing at The Drawing Center (May 6 - July 15).

A primary curatorial force behind both of these exhibitions is former Bostonian Elisabeth Sussman, whose history in Beantown runs deep. She earned all her academic degrees here, taught at Tufts and Harvard, and worked at the Institute of Contemporary Art, in various curatorial and administrative capacities, before becoming a curator at the Whitney. Fortunately for Hesse admirers, Sussman has been paying sustained attention to the work of this artist for many years.

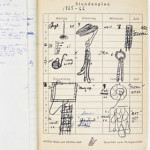

For Eva Hesse: Sculpture, Sussman was joined by Fred Wasserman, the Henry J. Leir Curator at the museum. The team has collected many of Hesse’s major sculptural installations in latex, fiberglass, and rope, along with drawings, archival material (including diaries and films), and recordings of the artist being interviewed (which they have interwoven with their insightful audio guide commentaries). It is a rare treat to see any of Hesse’s vulnerable sculptures exhibited; to see so many of them together inspires a reassessment.

When that same “Repetition Nineteen III” from MoMA appears opposite “Accretion” (1968, dozens of narrow, human-height cylinders, textured but erect, leaning slightly against a wall) and also near “Sans II” (1968, rows of molded box forms protruding from the wall), Hesse’s glowing, skin-like materials take on a unsettling undertone. Is it the exhibition’s placement at the Jewish Museum, or do her forms suddenly refer to situations from the concentration camps? The arrangements of her cylinders are never regulated -- they appear like bedraggled yet struggling people, gamely battling despair and listlessness (“Repetition Nineteen III”) or lining up at the wall to await a firing squad, tired but refusing to buckle (“Accretion”). And though “Sans II” has been described as a soft-edged Judd sculpture, its rectangles also resemble rows of concentration camp bunk beds, built shoddily for masses of dehumanized prisoners, but the fact that the forms stay turgid implies a dogged striving for some sense in existence. The fact that this exhibition ends with an entire room full of documentation of Hesse’s family history, including their escape from pre-WWII Germany, gives weight to this possibility. Yet Hesse’s use of light as a sculptural element prevents this reference from getting too lugubrious. And the artist herself would probably bristle at analysis of symbolic meaning in her work: she insisted that she prioritized the “total image” over any other concern for what her art could be. “Meat and life!” she cries, tapping along with the syllables’ rhythm for emphasis.

Sussman and Wasserman do not focus on the trials of Hesse’s life, nor do they sentimentalize the work of an artist who died too young (Hesse succumbed to brain cancer in 1970, at age 34). Even without these contexts, the sculptures radiate with delicate mutability and psychoanalytic complexity. The last pieces in this chronological survey, “Untitled (‘Rope Piece’)” (1970) and “Connection” (1969), show Hesse playing not just with gravity, but with forces that pull in the opposite direction: up. Looking through the suspended globby lines of the fiberglass and resin forms in “Connection,” the human connection is material: a visitor’s body across the room completes the visual connection between ceiling and floor, heaven and earth. Hesse’s forms feel like attenuated analogues for our own more gross and earthbound bodies. Geometric order is all but gone.

The curators deal with Hesse’s work in formal artistic terms, as well as offering ample contextualization. Their arrangement of the gallery space enriches the visitor’s experience: the newly exposed cement floor, painted for the exhibition, gives Hesse’s textures full reign. Their placement of “Sequel” (1967-68) off-kilter in relation to “Schema” (1967-68) not only highlights the contrast between one’s regularity and the other’s disarray, but it also recreates the floor plan of Hesse’s “Chain Polymers” exhibition at the Fischbach Gallery, the 1968 solo show that sealed Hesse’s reputation. Also, the curators generously offer edited clips from Hesse’s interview recordings -- visitors can listen from a bench placed to the side. Also available is a prodigious exhibition catalogue, full of images and essays (which was first created for the San Francisco version of this exhibition, in 2002).

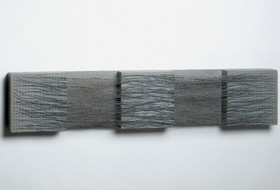

For Eva Hesse Drawing at The Drawing Center, Sussman collaborated with Catherine de Zegher, who recently left her Director’s position there. Here, a few pivotal sculptures complement the offerings at the Jewish Museum, such as “Metronomic Irregularity III” (1966). (Another version of this work was included in Lucy Lippard’s landmark 1966 “Eccentric Abstraction” show.) But the space is overwhelmingly devoted to Hesse’s works on paper, from all periods of her artistic development. The curators give equal honor to all kinds of works -- from sketches and scribbled notes to refined pieces and deliberately artful renderings of Hesse’s sculptures. Some surprises appear, such as two gorgeous graphite renderings of ordinary objects, and more than an entire long wall given over to early, brightly colored wild abstractions. On the other side of the room, a group of Hesse’s somber “window” watercolors seen together begins to look like a series of Rothkos in sepias and whites, but done with a lighter touch. Hesse’s touch is still serious, however, and yet it is also a bit amused. The drawings in this exhibition reveal the artist’s wry, wise, hopeful, and sometimes uproarious laughter -- her lines dance on the page, partnering with the total absurdity of life.

Links:

The Museum of Modern Art

The Drawing Center

All images are courtesy of The Drawing Center.