2008 ICA FOSTER PRIZE FINALISTS: A CONVERSATION WITH RANIA MATAR

On November 12th, the 2008 James and Audrey Foster Prize exhibition opened at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston. Rania Matar is one of the four artists competing for the $25,000 biennial prize, and Big RED editor Matthew Gamber caught up with her for a conversation about her work. This is part of a series of interviews with the Foster Prize finalists.

----

Matthew Gamber: Your recent body of work focuses on women and children who appear positive despite being surrounded urban devastation from the bombings. You arrived in Lebanon in the July of 2006, just before the Israeli forces began bombing Southern Beirut. Did you have a sense of a pending conflict, or was it merely by chance? What was it that made you want to return to Lebanon as a photographer?

Rania Matar: I arrived with my kids on July 12, 2006 to visit my family and work on some photography for a book project. The war started that same evening and we were in one the last flights to land before the war exploded. It was completely unexpected, even for people in Lebanon. We arrived on a full flight, and there were 5 other flights arriving from Europe at about the same time. The airport was mobbed with people arriving to vacation and others waiting for them on the other side. A few hours later, that same night, that same airport was bombed, deserted and shut down for over a month.

At that time, being stuck in a war with 4 kids and without my husband, I couldn’t think of myself as a photographer and just needed to get my kids out of the country, which we managed to do after a week, taking cabs with my father-in-law via Damascus. However I had decided right then, that I would get my kids to safety and go back as soon as the war is over to photograph the aftermath. Many people cover the war, for me it was important to photograph the immediate aftermath. It is an important part of the story that needs to be told, when the reality of war sinks in, when people have to put their lives back together and move on as they lost their loved ones or their homes, and when the world’s attention moved on to something else. This is part of the story that is often forgotten and ignored, so I decided to go back and photograph people’s lives immediately after.

My work does focus on women and children. I am a woman and a mother of four, myself. I can relate to women trying to protect their kids and shelter them from harm. I also find that they bear the brunt of wars and their resilience and dignity is humbling to me.

MG: In other bodies of work there is a subtext of how woman are adapting traditional customs in an encroaching outside contemporary world. Having ties to both the Middle East and the West, does this give you more insight to the subtleties of this transformation? Is there a personal connection that influences you?

RM: I grew up in Lebanon but have been living in the US since 1984. I feel that I have a foot in 2 cultures and am often saddened at the growing gap of misunderstanding between those 2 worlds. I photograph people in the Middle East to put a human face on people we often think of as different here in the West. I found that women who are veiled often fall in that category. Having ties to both the ME and the West give me insight to the subtleties and the possibility of seeing the 2 sides of the coin simultaneously. I grew up and lived in both Lebanon and the US and can see Lebanon from different angles. I am an insider who speaks the language, knows the country and understand its people, but I am also an outsider who can see Lebanon, its social and demographic changes and its complexities through Western eyes, and who can still get intrigued by the dichotomies that often go unnoticed by the locals.

The veil has many meanings and symbols in the Middle East. I grew up in Lebanon at a time when very few women wore the “hijab” or headscarf. I found that it has become quite a bit more the norm among Muslim women in recent years, and became interested in photographing that as a way of understanding the recent phenomenon myself. It did not influence me on a personal level as I am not Muslim myself, but I became intrigued by the meanings associated with the veil. In the western world, it is often perceived as a symbol of oppression. In Lebanon where a woman does NOT have to wear the veil, I wanted to understand the reasons behind it, and put a human face on the women behind it.

Lebanon is a country wedged between the West and the Muslim world, home to a growing Muslim society but also to a very western Christian population, providing different interpretations of female fashion, and a juxtaposition of the veil with a very western dress code and life style. The veil as a result carries different layers of meanings and can be seen worn in very different ways ranging from the traditional chador to a fashionable headscarf.

The Muslim population is growing larger due to a higher birth rate. It is highly politicized and seething with anger at the news coming from other areas in the Middle East. In addition, in a post September 11 world, it feels threatened in a world looking at any Islamic piety with suspicion, with a resulting retreat into more religious consciousness. The female veil, which was almost non-existent a decade ago in Lebanon, is making a comeback, even among the younger generation and often among women with a western education. It is having different undertones ranging from religious devotion, to self-assertion vis-à-vis the West, to a new item of fashion.

The topic of the headscarf in a country with strong western influence became interesting to me is that it provides a microcosm of what is going on in the world today in terms of the growing differences but at the same time the existing inter-dependencies between the West and the Arab world, or Christianity and Islam. It is not uncommon in Beirut to see veiled women walking next to women in mini skirts or tank tops, or under posters of beautiful supermodels, eating at McDonalds or having coffee at Starbucks.

MG: Critics of traditional documentary photography say that its time has passed, and that the golden age of the black and white still image has long since passed - its power and immediacy are shrouded behind an style that conveys only romantic notions of advocacy. However, there are those that argue that it takes this kind of compelling image made in an already understood method of description to raise awareness. How do you resolve the issue of photographing a very present topic with a very traditional form of photography?

I think photography has evolved and I hate to classify my work into categories, as I don’t perceive it as traditional or documentary. Maybe in some ways, perceived from the outside, it is, but I arrived to what I am doing from a completely different place as I found a topic that is meaningful and fascinating to me and found a means of executing it that felt like the right one. I might call it personal documentary. Photography and the subject I am photographing happened to me at the same time. I hope to have given my work my own personal voice, in the sense that it is very personal to me. In that, I mean that I did not follow a specific certain set of rules, or set up to find a topic to photograph.

Everything I have lived and done so far seems to have converged into what my work is today: my background and training as an architect, my interest in modern painting my role as a woman and a mother, and my belongings to two cultures, are what would describe my work, and explain how it came into being what it is today. As such for me this is very personal and I don’t perceive it as documentary or traditional. I deeply hope to have found a way to give it my personal touch and vision.

As for BW, I found that it was for me the best way to focus on the person, on bringing a certain level of abstraction from the reality, on focusing on the human without any distractions. The color work exhibited at the ICA had to be in color, as its strength was in seeing bursts of color in an otherwise gray surrounding of rubble. We are lucky in this day and age to have all the options on the table and choose what feels right for the right subject. The technical evolution of the medium of photography makes it an art of our times and adds an infinite number of possibilities. Now using BW is a choice, not a requirement.

I would also like to add that when BW was the only traditional way of doing documentary photography, the images used to be rather small and presented in a certain manner. Now there is a contemporary aspect to the work as we have the means of scanning negatives, and printing digitally at any size. As such presentation, content and subject, size of images and a contemporary framing are other components that could add a layer of differentiation to the work from its traditional counterparts, call it evolution. One can use a “traditional” medium and make it contemporary through the infinite present possibilities available to us in this day and age.

MG: Do you feel your photographs testify to the truth of the environment, or do you feel the end result is more like how Robert Frankdescribes his images – as internal feelings projected outward?

RM: The photographs are true in that they are the representation of an exact moment in time and place. The personal aspect comes from the choice of taking that specific image when many other things were going on in the same place at the same time, the choice of framing that image in that exact way (I mean the frame of the negative at that point) and not another, and the choice of what to include in that frame. So it is a reality but it is a piece of the reality that has been perceived by the photographer (me) at that moment while something completely different could have seemed more interesting to someone else. For instance in the image of the woman completely covered in the university, one can see in the background on the right other students dressed in a western manner gathering around a picnic table. One could have taken a portrait of that same young woman by moving a little to the right and the students in the background would not have been in the photo. Then the reality, which is still the same, would have given life to a different environment and feel for the photo. This is true for all the images.

Another component comes into play is the editing and the context and placement of the image. This is very personal to the photographer and brings the internal feelings of what the photographer would like to show, by virtue of image choice, sequencing, placement and presentation.

So, I think both statements are true: the image is a truth of the environment, but it is also very much a reflection of my internal feelings of what seemed important to me as the photographer in that place, at that time, of my interpretation and what I chose to convey. This is why at the end, the work is personal to me, to what I saw and felt at that time and place, to the choice of what is in the image and the choice of imagery to include in the presentation.

MG: How do you manage the desire to describe something well, while making an aesthetic image? Do you these are two conflicting concepts, or are they hand and hand?

RM: There is so much beauty around us, even in situations that don’t seem “beautiful”. I try to see the beauty in people, in their dignity and their resilience and focus on that, even when their surrounding is not per se beautiful. I feel that I owe it to the subjects I am photographing.

When there is a subject or a situation that I find interesting, I photograph quite a bit, from different distances, different angles, and am very aware of the composition and the content. Then editing comes into play. When the moment has passed and I look at all my images later, with a clearer eye and mind that when I was taking the photo, in the sense that I am now removed from the immediacy of the moment, I find that often the images that stand out, that are the most successful and describe the subject or the situation in the most powerful way are the ones that managed to combine aesthetics and content. I don’t think they are conflicting concepts.

On the contrary, they complement each other, and it is important to learn to achieve both simultaneously. This is when I know I got a great image, the “yes” moment that Henri Cartier-Bresson talks about, when everything aligns to make the picture successful: the moment, the composition and the content. I am working on a book right now, and in the book, I might include some images more for their content than their aesthetics as they might help tell the overall story, but for an exhibit one has to show the strongest images and they are the one that can combine both successfully.

MG: You originally studied architecture at the American University in Beirut, and then later at Cornell University in New York. How did the transition to photography happen? I’m interested in how that previous skill set might have translated into your thinking about how to approach photography.

RM: I studied architecture and then worked as an architect for a few years after graduating from Cornell. I had taken numerous art classes at Cornell - painting, intaglio, charcoal drawing, etc, ironically never photography! When I had my fourth child in 2000, I wanted some time off from architecture and signed up for photography workshops at the New England School of Photography, mainly to take better photos of my kids.

However, a year and a half later, when I was in Lebanon visiting family, I went with a cousin of mine who was doing a documentary movie about a Palestinian refugee camp in Lebanon. This was a turning point in my life. I had grown up in Lebanon, maybe a 5 min car ride from Shatila, one of the camps in the immediate outskirts of Beirut, and had no idea that people lived in such despicable conditions so close to the cosmopolitan Beirut I grew up in. Also all we heard in the news in the US about Palestinians, was often associated with terrorism, and all I saw in the camp where beautiful kids playing in the narrow alleys and people trying to go on with their lives, people who were warm and welcoming. I decided to start photographing life in the camps and tell the stories of the inhabitant through images. I worked on this project for the next few years, fell in love with photography as a means of making art while telling people’s stories, and never went back to architecture! Eventually the project expanded to include other subjects around Lebanon and some in Syria. But this was the turning point. Somehow something clicked and I felt, as I mentioned above, that everything I had done before converged into this: my background, my education, my life in 2 countries, my role as a mother, my love of art, everything.

On the technical aspect, my architecture training definitely played a role in the way I saw and photographed things. I was always very aware of composition, texture, light, and background/foreground. It was already all inherently part of me and I don’t think my architectural background could be denied when viewing my images.

MG: You’ve worked with a number of non-governmental organizations like American Near East Refugee Aid (ANERA) and The Kanafani Foundation. Can you describe process of how these organizations work with photographers?

RM: When I started photographing in the Palestinian refugee camps, I very much felt like an intruder and an outsider. I was taking images of streets and alleys and never allowed myself to get close to the people I was photographing, as I was always very self-conscious of offending them. Eventually I met someone here in Brookline, whose cousin runs an NGO in Lebanon. (In a very funny twist of events, I met him as our kids were playing soccer on the same town team). He introduced me to his cousin who worked with the NPA (Norwegian People’s Aid) in Lebanon and worked closely with many families in the refugee camps. All of a sudden I had full access and gained people’s trust almost instantly as I was not a complete stranger anymore, but I was accompanied with someone they trusted. This was important, as I really wanted to portray the intimate lives of people, get close to them, hear their stories, etc. and to accomplish that, I needed a level of trust that I might not have been able to acquire without a proper introduction from the inside. Eventually I built my own relationships through the ones I had made, but also eventually I met more NGOs working in the camps and they helped me meet more people in other locations and get access into their homes. Because of the NGOs I was able to build relationships, and photograph people in their intimate surrounding.

As a way of thanking the NGOs, I often gave them photos to give back to the families and CDs of images that they could use for fundraising purposes. On occasions I photographed subjects or events that were of specific interest to them, such as their medical care, or whatever they could have needed along the same lines. It was a collaboration of some sorts. I was humbled by the work they do, while not getting much in return, work that is often not recognized or acknowledged, but that is essential in the lives of many families.

- Rania Matar, Girl and Rocket Hole, Aita El Chaab, Lebanon, 2006.

- Rania Matar, Sisters Photo, Beirut, 2006

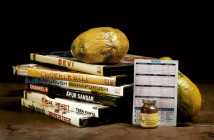

- Rania Matar, Newspapers, Beirut, 2007

2008 ICA FOSTER PRIZE FINALISTS: A CONVERSATION WITH ANDREW WITKIN by MICAH J. MALONE in issue #95

The Institute of Contemporary Art

"The James and Audrey Foster Prize Finalists" is on view November 12th, 2008 - March 1st, 2009 at the ICA.

All images are courtesy of the artist and The ICA.