By MATTHEW NASH

It has been a few weeks since the Boston Foundation's "Vital Signs" report (pdf) was released, and it is still a topic of conversation and heated debate. Among those who are on the lower-budget end of the non-profit spectrum, the report inspires passionate outbursts every time it is mentioned, with many angry over its conclusions and research methods.

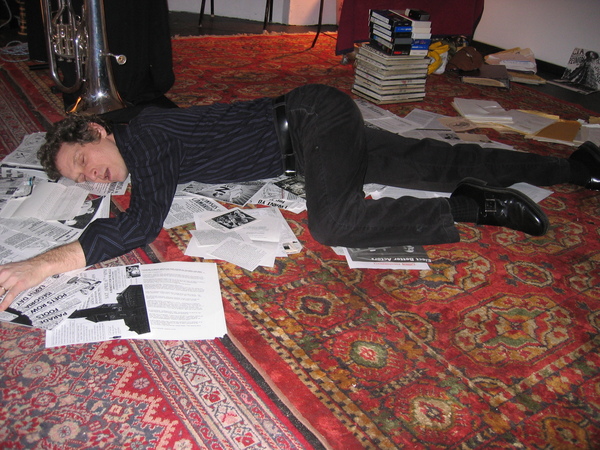

Artists, of course, are not ones to lie down quietly. Last night, a group of visual and performing artists staged a "Die-Off" in mockery of the report's conclusions. They drank Kool-Aid like Jim Jones cultists, and ceremonially killed their non-profit organizations. The "mass suicide" was, of course, meant to call attention to the very serious implications of the "Vital Signs" report. Ian MacKinnon of Artezani Theater organized the event, and his invitation read:

Is your small arts group feeling hopeless? Tired of bashing your head against the wall? Do you suffer from artistic depression? According to the latest report of the Boston Foundation, if your small arts group's "vision either dissipated or lost its resonance with its audience or supporters," you should think about pulling the plug. Of course, you've thought of ending it all before, but now a Major Player in the Boston arts scene is calling out to you with an expensive new study. Look deep into your heart. Consider how fruitless it all seems. Think of the burden that will be lifted from your shoulders if you answer their call for small arts groups to die.

The controversial text that inspired this mock-mass-suicide comes from the "Looking Ahead" section of the report:

Consider exit strategies. If a nonprofit lacks a clear vision, struggles to attract audiences and donors, and cannot grow to a larger scale, it should consider exiting the market or merging. The dynamic of organizations leaving the marketplace in the for-profit sector is not replicated in the nonprofit sector. Instead, boards of directors and staff leadership struggle to survive even though the vision has dissipated or lost its resonance. Exiting the market is a difficult issue, particularly because boards may view it as their fiduciary responsibility to sustain an organization regardless of circumstances. However, because a healthy sector must allow nonprofits to enter and exit the marketplace so that innovation can flourish, nonprofit boards and institutional funders need to ask if an organization has run its course. (pp.9)

This is very interesting advice, considering the last decade and how many smaller and alternative spaces have come and gone. The report addresses these spaces in passing early on:

In the lower budget range, evidence of churn (organizations entering and exiting the market) suggests there is room for innovation. Several organizations increased in scale over the period of this study-a good sign. Subsectors- performing arts, museums, multi-media-are growing at uneven rates. But we don't know enough about the appropriate level of sector dynamism and change to determine if the churn is adequate, if uneven growth is acceptable, or even if there is enough room for organizations to go to scale. (pp.8)

Looking more deeply at the dynamics of organizations within different budget ranges, data analysis shows little change in the share of population and revenue in any budget category. However, an examination of the number of organizations entering and exiting the market-the churn-shows that the majority of turnover takes place among organizations in the lowest budget category. (pp.18)

Both of these quotes can be found in the introductory section of the report, and its hard not to read between the lines. "Churn" is good in the low-budget end of the sector, but they "don't know enough" to make a determination about its effects. Yet, just a page later, they encourage non-profits to "[c]onsider exit strategies", and get out of the way so that the "churn" can bring in new and more marketable organizations.

On the face of it, this is not a wholly unreasonable suggestion. In a healthy non-profit sector, we would hope to see new venues and organizations clamoring to become part of the sector, and a heated competition between established groups and newcomers for audience, funding and visibility. The fact is, though, that we are not seeing many new entrants into the fray, and it must come as a slap in the face to many groups who have been working hard to hold on for any length of time to be told to "consider exit strategies." While one could certainly argue that Boston's "low budget" non-profit sector overextended itself in the 1990's, and that some contraction was inevitable, the fact remains that we saw many good spaces close up that weren't replaced by others. The "churn" that is necessary to make an argument for removing some organizations depends on an influx of new groups that, frankly, do not currently exist. With a looming recession and rampaging urban development driving many groups into retreat, it seems much healthier to support those that have a foothold, and find ways to encourage new spaces through means other than killing off their competition.

Admittedly, the Boston Foundation report contains much more than the few paragraphs quoted above, and much of the advice is very sound. I've only highlighted the passages that have drawn such a sharp response from artists and some organizations. Certainly our larger institutions, such as the ICA, MFA and others, are doing fine. On page thirty-five: "Positive trends in leisure tourism may translate into increased audience, but only for a small segment of the arts and culture sector."

Even this positive indicator, though, tells a frustrating tale. While the sector that feeds new artists, ideas and innovation into the city is slowly strangulated, the organizations that support the least innovation and rely most heavily on smaller venues for the kind of experimentation and growth that leads to great art are growing. No artist will have their first exhibition at the ICA or the MFA, but if our alternative scene contracts any more, the health of the arts in Boston may only be measured by the number of artists leaving for greener pastures.

Overall, I know that Boston is healthier than that, and the "Die-Off" actually proves to me how much resistence there is to the idea of giving up, and much fight is left in our art scene. Artists and groups refuse to be declared dead, and may be riled up enough to prove that this long contraction is finally over. There is a vast amount of exciting energy among artists, performers and the arts audience in Boston. It is adapting and changing to meet new circumstances, and pushback against this report is one of many signs of a healthy and vibrant art scene that continues to push on in the face of daunting odds.

Citizens for Art that Responsibly Entertains

The Boston Foundation

Geoff Edgers reports on the "Die-Off" in the Boston Globe

"The Small Arts Group Die-Off" occurred on Sunday, January 13th, 2008 at The Outpost.

Click here to view more images by Christian Holland from the event.