By JESS T. DUGAN

Jess T. Dugan: How did you begin making photographs?

Susan Wides: My first photo project was a booklet of aerial photographs of the World’s Fair in 1965 shot from the Monorail while traveling above the spectacle! In college I had the opportunity to study with the important teacher and artist Henry Holmes Smith. He came from the New Bauhaus in Chicago. He was a mentor for me and a living window onto Modernist history. The Bauhaus idea of not simply documenting, but to help people see in extraordinary ways -- slowly, abstractly, closely -- is an influence to this day.

My time is divided between NYC and Catskill, NY. Their landscapes and their connections with our country’s history, memory and art have inspired me to develop two current series, Kaaterskill and Mannahatta. In these new works, I explore the specific character of each place through their cultural, historical and personal significance to me.

JTD: Can you talk a little bit about your Kaaterskill pictures and how that project came to be?

SW: Kaaterskill developed out of my interest in the area surrounding our upstate home, a historically fascinating and geologically dramatic part of the Catskills. I first discovered an immense car junkyard when I went to get spare parts for my old VW. I was fascinated to learn that this was right down the road from one of Thomas Cole’s chosen places to paint. As I delved into the history of the area and of the HRS, I also became very curious to compare the sites as they are depicted in the paintings to the way they look today, so I began tracking down more of these locations. As I hiked to the sites of the paintings and began developing my own perspective about the area and my own connection to the spirit of the place, Kaaterskill became about the experience of the Catskill landscape today and as it exists in our collective memory.

JTD: The original Hudson River School paintings idealized and romanticized the landscape, often falsifying the truth in order to portray a more beautiful world. Do you feel you do the same with your photographs, or do they take on a more critical role?

SW: The new significance of nature and the development of landscape painting coincided with the relentless destruction of wilderness in the early 19th C. For example, only ½ mile from the Kaaterskill Falls, where generations of HRS artists and writers and tourists pilgrimaged, a tremendous amount of industry was being conducted including: lumbering, tanneries and quarries. The painters did not depict this. Of course human/land/technology interactions are a large part of my work which does takes on a critical role.

The work addresses the environmental themes that were beginning to emerge in the 19th century through the Hudson River School and continues to speak to environmental issues confronting us today. And it is a meditation on painting and photography’s ability to communicate a transformational experience of landscape.

JTD: You use extreme camera movements to exaggerate certain aspects of your image. How did you come to work in this particular style?

SW: My work emphasizes an uncanny moment when an image is simultaneously indistinct and sharp. As in half-remembered memories which might just be half-forgotten dreams, my photographs echo the strange ways memory works. The images oscillate between blur and clarity, fact and fiction, past and present, reality and myth. This tension and the work’s multileveled meanings encourage the viewer’s active participation in making choices while experiencing the work.

I have used selective focus extensively since my wax museum series in the early 1980s, which also was a cultural critique. When the figures are out-of-focus and indistinguishable from real people, the focus technique accentuated the blurring of fact and fiction in the museum and most importantly in our time. The methodology of selective focus has also been integral to my botanical garden series in which I deconstructed the names of the roses in the early 90s. Here I used a 35mm camera to make close-ups and used a wide aperture in order to allow only a small area of sharp focus. I placed a mask over the lens, which allowed the edges of the image to be in sharper focus. This was fantastic because I was able to have more control over sharpness and blur in the photographs.

The methodology I developed in those projects let me to the way I currently use the 4x5 in the landscape in my long-term Mobile Views series which I began in 1997. In order to capture the way the eye tracks the landscape and the body experiences the space, I paid attention to a subtle kind of looking, a super-attentiveness, a kind of meditation on certain elements in the landscape while walking. It was this kind of perception that I wanted to make photographs about. I began to experiment and soon discovered that the 4x5 view camera, with its moveable lens and bellows gave me a much wider range of possibilities for selecting the areas of focus in my images than the masked lens I had used on the botanical garden series.

JTD: Such extreme use of camera movements has been criticized by some as a “trick.” Do you feel like your images depend on this “trick,” or do you feel like it is just another tool used for making an image?

SW: The use of selective focus is a very flexible tool for my purposes. My entire Mobile Views project uses this method, which comprises a number of series including Kaaterskill, Mannahatta and Fresh Kills. Suggestive of the panning, tilting “mobile frame” of the movie camera, my perspective embraces the fluid, the changeable and the view through the lens, so central to our way of seeing today.

JTD: Do you feel that your work manipulates reality in order to bring into focus a more subjective truth?

SW: The subjectivity of vision has been a preoccupation of my work for many years. The technique replicates the way the eye darts from place to place across a landscape, focusing in on certain details while ignoring others.

We live in the Global city, bombarded by a sea of images that have permeated our consciousness and, paradoxically, prevent us from seeing. Yet, in order to truly connect with a place, we must still walk outside, breathe its air, soak up its light and experience its space and its history. I appraise the site, allowing the “spirit of place” as Strand called it, to seep into my mind’s eye, my inner lens. I invite the viewer to join me at the moment of discovery when perception suddenly changes and the recognizable and familiar image is re-imagined.

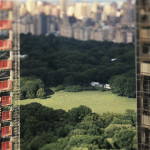

JTD: Could you speak about the photographs you made in New York? In many of your images, the viewer is unsure whether they are looking at an image of the actual world or of a model. To what extent do you want your viewer to question the authenticity of your images?

SW: I wanted to continue my particular portraits of NYC, mapping the almost daily urban transformation caused by the current building boom, the largest in the history of the city. It’s important to keep the vieer aware of the lens as its view reflects the way we experience memory, history and oneself through the multitude of images we encounter daily. The altered image offers a suitable way of showing the reality of our world today.

The oscillation between fact and fiction so crucial to my early work in the wax museum is a central concern here too. The viewer must look really closely to decide if this is a model or a real landscape. In my work, I try to balance an acute awareness of the past with witnessing our time with authenticity instead of nostalgia or escape.

JTD: There is an ongoing debate about the photograph as “truth,” and what responsibility photographers have in capturing and representing this truth. With the rise of digital technology, what qualifies as a photograph has been called into question, giving rise to such terms as “digital painting.” With such painterly, subjective images, where do you feel that your work fits into this debate?

SW: I use the urban landscape as a palette from which I derive images and recompose them to reflect on the significance of images in our culture.

It’s important to me that my work is done “through the lens”. My images are printed digitally.

JTD: Similarly, what is your opinion on the responsibility of photography versus the use of the medium purely to express the individual vision of the artist?

SW: Photography is a language with a lot of purposes. As an artist my responsibility is to express my vision. My responsibility to photography would be different if I was doing photojournalism, which I am not.

Susan Wides will be presenting and speaking about her work as part of the series “Light Conversations: Seminars with Contemporary Photographers” at the Fogg Art Museum.

- Susan Wides, Mannahatta 7.2.07 (Sheep’s Meadow), chromogenic print, 2007

- Susan Wides, Hudson River Landscape (Near Catskill Creek) 10.15.04, chromogenic print, 2005

- Susan Wides, Hudson, New York (Hudson) 1.3.98 , chromogenic print, 1998

Susan Wides

Kim Foster Gallery

Susan Wides will speak as part of Light Conversations: Seminars with Contemporary Photographers on Monday, February 11th at Mongan Center, Fogg Art Museum, located at 32 Quincy Street 11:30 a.m.- 12:30 p.m. Admission is free.

All images are courtesy of the artist and Kim Foster Gallery