KARSH 100 @ THE MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON

Walking into Karsh 100: A Biography in Images, an exhibition of Yosurf Karsh’s photographs at the Museum of Fine Arts, I found myself face-to-face with Winston Churchill. Not the real Winston Churchill of course, but rather a large black and white portrait of his stern face staring at mine with disapproval. My first reaction was to look away, a symptom of my own non-confrontational nature, but clearly evidence that the expression rendered in the photograph had an effect on me. As other viewers shuffled past I noticed their comments were restricted to pointing out the identity of each person in the photograph. No references were made to the composition, the emotional aspect, or any other idea, only, “Hey that’s Einstein”, and, “That’s Mother Theresa.” As I stood having a staring contest with a chain smoking Mr. Tennessee Williams I wondered what made these portraits so compelling to the masses, to those without a background in the visual arts? Are these images only interesting because of the subject matter or are these photographs the difference between a portrait of someone interesting and an interesting portrait of someone interesting?

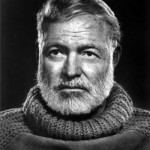

This show marks the centennial of Karsh’s birth, exhibiting work that exemplifies his career spanning 60 years. At the time of his birth, photography had been in existence for a mere 74 years, a newborn of a medium. Best known for his studio portraiture, Karsh immortalized the great icons of our time, a feat that that not too long ago was thought impossible. "People of Consequence” he called them: actors, composers, writers, scientists, politicians, visual artists, and women of the church. 74 years prior to his birth their faces would have been forgotten, idealized and altered by the perceptions and aesthetics of painters. His style is quite different from contemporary portrait photographers such as Avedon, Liebowitz, and LaChappelle whose use of stark commercial lighting creates a somewhat removed and isolated mood. In contrast, Karsh uses a very subtle approach to his subjects; their personalities reflected in props and accented with soft artificial lighting. This creates a warm, romantic tone in the photographs.

In the open space of the show I found Karsh’s 8x10 view camera set up in such a way that by cupping my hands over the ground glass I could see Winston Churchill upside-down and backwards. While walking throughout the space I noticed many gallery-goers perplexed by the imposing monorail and clearly impressed with the scale of the old technology and slightly ashamed of their 2-mega pixel camera phones. For some, the monorail is just the tool he used, but based on the comments overheard it made looking at the images more of a challenge to wonder how they were achieved with a camera whose function they did not comprehend. Displayed next to this he is quoted in his biography as wanting to capture the soul of the person, their inner power. Side by side on the gallery walls black and white images mounted on white mats in black frames, traditional in every sense, hold personas. The props chosen, the lighting, artificial and inspired by his days in the theater, left me unconvinced that Karsh succeeded in finding the soul of his subjects, but rather in cementing their public personas as icons.

This is not to say the photographs are unsuccessful, on the contrary, each one beautifully illuminates the characteristics of the subject. Peter Lorre, so softly lit on his three-quarter profile, accentuating his expressive eyes and obscuring his more anonymous features in shadow suggests to the viewer an intimate look at him, but as Lorre the actor, the character, not as Lorre the man. It is all too easy now to disregard portraiture as a carefully crafted art form when on a daily basis we are bombarded with faces peering at us from magazine shelves, leering from billboards. Walking through the show it was refreshing to see portraiture as an art without trying to sell me something. In a room full of people looking out at me, I am forced to look back. The images are carefully composed and as I come to each portrait I react differently. Some challenge me with their gaze, some look put out; some don’t look back at all, inviting me to linger a bit longer. Karsh 100: A Biography in Images is an appropriate title for this exhibit. The work is as much a biography of Karsh as it is the people he photographed. It is curious at how we judge the talent of the artist by the faces of others.

So what makes these traditional black and white portraits so compelling? While they certainly are photographs of interesting people, it is the way I am forced to interact with people who have long since passed, the way a two dimensional image can make me feel uncomfortable, and how Winston Churchill will never be just a name in a book to me again, but rather a grown man of consequence pouting at the photographer who removed his cigar by force and how his disapproving look can make one feel guilty for not stopping it.

- Yousuf Karsh, Winston Churchill, gelatin silver print, 1941

- Yousuf Karsh, Ernest Hemingway, gelatin silver print, 195

- Yousuf Karsh, Ford of Canada, gelatin silver print, 1951

"Karsh 100: A Biography in Images" is on view until January 9th, 2009 in the Raab Gallery at Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

All images are courtesy of the Museum of Fine Art, Boston.