NATHAN LEWIS @ SETON ART GALLERY

What if there was painting that mattered? There is an unequivocal answer to this question in the survey of work by Nathan Lewis now on exhibit in West Haven, Connecticut.

Nothing is to be found here of those artists whose technique is their only subject. Lewis's skill with paint - painstaking and inventive - is literally invisible; at the center of his art is an imagination that defies inevitability. His is the free world: honest about its terrors, but not reducible to them.

There is a narrative here - without sequence, but presented as the intersection of story, where threads of art and politics overlap. The lost records being restored in these images are not offered as exercises in either nostalgia or conceit. Rather, they are instructions in how the individual can take charge of history in ways that the official archives would rather forbid.

Lewis's chosen iconography is personal without being mysterious; even in those cases where recognition might prove unlikely, those cases are no more rare than the daily confusions the world ordinarily offers. No cypher book or glossary is necessary; there is an implicit trust that all witnesses to the work carry a catalogue of shared culture - both popular and exotic - from which we can select workable instruments for reading Lewis’ revisions, and to which we are invited to contribute.

The centerpiece image of Until We Find the Blessed Isles Where Our Friends Are Dwelling for all its obvious allusions, cannot be reduced to a single quotation. While George Washington is clearly afloat here on a thawed Delaware, the Raft of the Medusa, is also present, with Géricault's mortuary faces arisen live to the sunlit pink of a museum mural's fantastic geology. This is a flash flood that will carry craft and passengers outside the frame, leaving a landscape of dry bones behind. Unlike the mad cook of Apocalypse Now who vows to "never get out of the boat," this crew of survivors is meant for the promised land.

In The Blessed Isles, there is a camera shutter about to click shut on the universe, or a spinning carnival wheel of fortune with heaven at the center wherever it clicks to a stop. Punctuated with botanicals, electronics and Fred Astaire drummers, this is the vortex of definitive public myths - those happy lies which keep us sane.

Beneath these two canvases, an installation entitled Marlow - equally evoking Humphrey Bogart, Joseph Conrad and the Exxon Valdez - trails gasoline cans like bait floating on the gallery's carpeted sea.

Under My Thumb (History of the World, Part 1) is a sports event for the apocalypse, played in sight of the rubble. This is not the warrior football of M.A.S.H. The frenzy of this overpopulated playing field is only apparent, with each player completely independent and unrelated - a mob of solitary athletes, using derricks as goal posts for the only - and last - game in town.

Second Life takes place beneath the dangling legs of a barefoot paratrooper or a levitating yogi, where the last, tardy pilgrims on the road to Canterbury consult their outdated maps. As in several of these paintings, birch trees are omniscient, echoing Robert Frost, who would:

"...climb black branches up a snow-white trunk

Toward heaven, till the tree could bear no more..."

The stripped fields in the background might have once held a scarecrow from Oz with his arms whirling to indicate all possible routes.

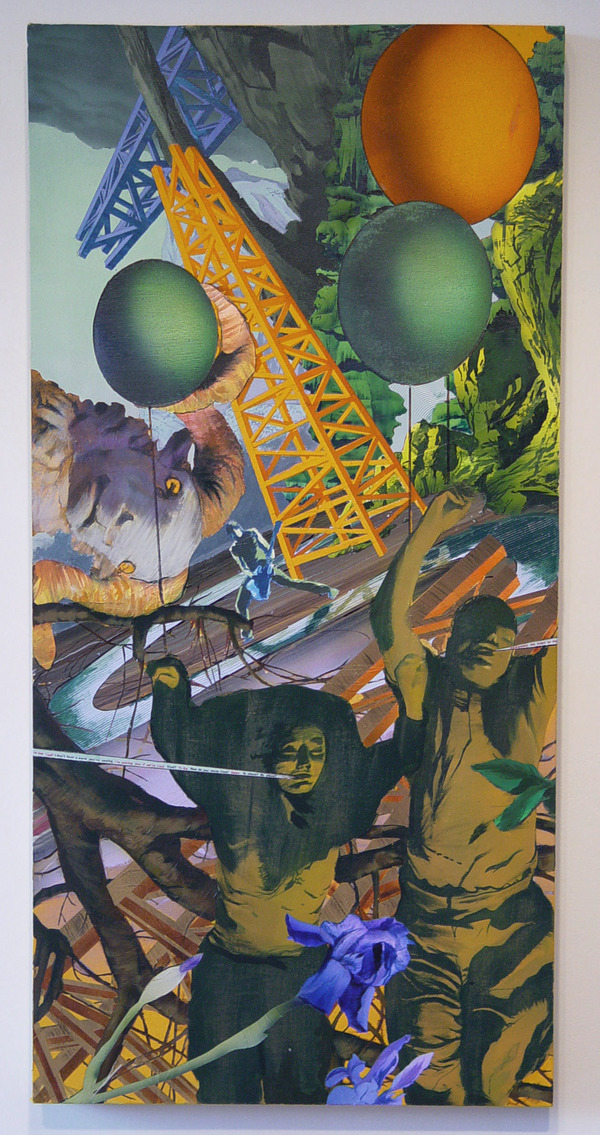

Strange Fruit has a special kind of completeness - a summary work with Lewis's characteristic reversals of time and place. Here Mussolini and his mistress are sinking upright underwater rather than hung head down from a metal canopy as they were by their killers, their corpses speaking Beckett in the company of balloons or buoys shining like candy. Derricks - the scaffolds of contemporary executions - are accompanied by guitar; and irises tilt across a frame in which there is no central axis or still point of view that is either necessary or final.

Like a casting director for folk tales, Lewis frames and reframes his recurring characters. Here are Charlie Chaplin rifles with popgun smoke, a cross culture of servants, demon rams, and the pointed fingers of creation or accusation or the funhouse exit or the hand of a detective squatting at a crime scene. Texts are integral even when unreadable, with the edges of the stretchers made into frames of words.

In Mocking Bird - with its trees growing out of the ruins of the Hudson River School - the title rings inside a painted question: "Can you triumph over this thought", that there is nothing left to do that has not already been done? Lewis succeeds in winning that contest, showing us that we do not yet know - in this warring world - all that we desperately need to.

- Nathan Lewis, Strage Fruit, acrylic on yellow canvas on panel, 2006

- Nathan Lewis, Till We Find the Blessed Isles Where Our Friends Are Dwelling, acrylic on canvas, 2008

- Installation shot of Seton Gallery featuring, Marlow, with Where Heaven Made Fun behind

"Where Heaven Made Fun: A Survey of Works by Nathan Lewis" until September 26 at the Seton Art Gallery, University of New Haven, West Haven, CT.

All images are courtesy of the artist, the author, and Seton Art Gallery.