Architecture is the expression of the very being of societies….In practice, only the ideal being of society, that which orders and prohibits with authority, expresses itself in what are architectural compositions in the strict sense of the term. Thus, the great monuments are raised up like dams, pitting the logic of majesty and authority against all the shady elements…

Moreover, the human order is bound up from the start with the architectural order, which is nothing but a development of the former. Such that if you attack architecture, whose monumental productions are now the true masters all across the land, gathering the servile multitudes in their shadow, enforcing admiration and astonishment, order and constraint, you are in some ways attacking man.

Bataille wrote about the ways in which architecture codifies the ideals of a society, inscribing acceptable patterns of behavior and belief into the fabric of daily transaction. This it most certainly achieves. Churches and cathedrals demonstrate the power of religious institutions, malls and department stores shelter and advertise consumption, atriums and antechambers demarcate power, and even ‘non-architectural’ elements of our built environment: sidewalks, curbs, railings, speed bumps, etc., encode and reinforce social systems and predilections.

But architecture by definition also does something more personal and insidious than this. The nature of buildings, especially those buildings classed by aesthetic success or intended design strategy, involves making a public display of prejudice. An idealistic architectural connoisseur will describe architecture in terms of public art: its design and making – its finished presence -- is a gift bequeathed to the public landscape: something everyone with access to the public realm can appreciate. This is true to some extent, because any pedestrian can admire and judge the façade of a building, its massing and fenestration, its proportion, symmetry, and gestural emotional qualities, in the same way they can admire and judge any public art.

However, the great difference, the definitive difference, between public art and architecture is the inside, the program: the fact that this edifice, this embodiment and fortification, is not only erected to confront and interface with the public, but it also protects and inscribes the use which the architects, engineers, contractors, etc., have been paid to instill at the pleasure and cost of the client. Anyone who has been involved in this field for even a brief duration knows this to be true: architecture reinforces the clients’ priorities much more than it adorns or intervenes or is purposed to do so. Instead, its primary motivation is to strengthen and extend the pre-existing imbalances and inequalities treasured and maintained in a society where some have the resources to build and some do not. In other words, architecture prescribes its ideal user to the exclusion of those for whom designs are not made, and it does this with astonishing permanence.

This property of architecture is true regardless of scale or beneficent intent. The same inclusion of those for whom designs are constructed and exclusion of those for whom designs are not, exists in residential architecture and civic architecture alike. So-called public buildings, like public libraries and schools, inscribe and defend the priorities of the clients every bit as much as private dwellings. Where the client relinquishes control, other pre-privileged entities, like star architects or community leaders, simply step into the role. Architecture is a vehicle which permits privileged or successful people and institutions to render their dreams, desires, and priorities in relatively indelible language, and in public. And architecture’s impact extends beyond the individual aims of any one client: money is still somewhat subordinate to law, and law literally codes and commissions the society’s notions of acceptability and decency. Architecture is thrown up within the context of an already constructed field of laws and practices which prescribe society’s tolerances. Good architecture not only conforms to this pre-constructed landscape, but also internalizes and reinterprets these guides in seductive and delightful ways. The code requires a minimum in the way that a teacher assigns homework, but a good piece of architecture does the exercise and invents extra credit.

What are the ramifications of this industry of permanent prejudice and overachieving obedience? It is attacked. The scale of the attack ranges from etching acid on a storefront to engineering spectacular and gruesome plane crashes into the World Trade Center towers. The individuals who attack architecture range from immature art students to terrorists. The motive, however, is what concerns us here, and the motive, while ranging in execution from nuisance to murder, is constant: it is against the client, and therefore against the established order of man which empowers the client. It may be incidentally against the designers and constructors who render the client’s wishes, or against the users or employees who occupy the space, but only as collateral targets; the intended victims are those who purpose and finance these monuments to buttress their vision and their priorities in the public domain.

This is the danger point for members of society who render their needs and desires in architecture: that medium is as removed in impact from public art as public art is removed from gallery art, produced to function in the private realm and to be enjoyed in that realm. The danger devolves from the fact that architecture is public, truly public, and is not exposed only to invited and similar guests in a private arena, or even to good, functioning fellow-members of society. Architecture is erected in the realm that includes members of society and marginalized non-members of society, those that abide by and prescribe the codified rules that Bataille railed against, and those that rail themselves, feebly, or with determination, fanaticism, and strength.

The truth of the matter is that architecture is separate from the noble arts because it embodies the strength of those who are already strong, and does so blatantly in the territory of those who are already weak. Not only does it celebrate and reinforce this dichotomy, but it does so by throwing up and fortifying barriers which precisely delineate the limit, the absolute frontier, of free and public interaction and action. The line between the sidewalk, which is itself the artificial construct of society, but which is public, and the architectural program, which is privately motivated, privately funded, and private in admission, is architecture, built, indelible, and dumb. This silence –reticent? proud?—is endured and appreciated by those who feel enfranchised by the rules and potentials of normative, acceptable endeavor, and resented and despised by those who do not.

The qualities that distinguish architecture from other built artifacts, like sculpture, or other places which allow for certain uses, like parks or plazas: structure for a particular program along with an aesthetic achievement, are the qualities which make it something powerful enough to warrant attack. The fact that it must interface to some degree with the public environment, that portion of the universe which is outside its purposive enclosure, is what makes it available for that assault. How can those of us who are engaged in realizing architecture learn to evolve more equable and less offensive systems of making? If the weakness of this endeavor, as Bataille points out, is its superior strength and longevity compared to the men who purpose it, perhaps the answer lies in more temporary, more portable, and more affordable creations. Could the future of this field of permanence and defense involve the transition to a transitory and engaging architecture, allowing for those outside a fragile and fragmented façade as well as those within? I hope so.

Links:

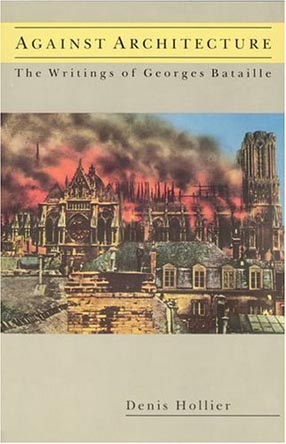

Georges Bataille

Against Architecture

All images are courtesy of the World Wide Web.