By JESS T. DUGAN

Moyra Davey is an artist and photographer, based in New York. Her current exhibit, Long Life Cool White, is currently on display at the Fogg Art Museum, featuring work from her 2008 publication by the same title. Contributor Jess T. Dugan interviewed Davey for Big RED & Shiny this March, and below is the transcript of their conversation.

•

Jess T. Dugan: How did you begin making photographs?

Moyra Davey: I began as a teenager in an improvised darkroom in a closet—I made a lot of solarized, hippie-looking stuff. I went to art school for drawing and painting, but dropped out after a year and then went back to do design, and eventually photography, at Concordia University in Montreal.

JTD: Can you speak about the concept behind your work as a whole, specifically the projects represented in the show Long Life Cool White currently at the Fogg Art Museum?

MD: I’d say that these pictures are about the life of objects. I had a funny revelation recently--and in a way this takes me back to my art school days as a nascent photographer--that my Fridge picture is very similar to Edward Weston’s toilet. In his diaries and notebooks, which I read in my early 20’s, and loved, he talks about photographing his toilet over and over, each time refining the composition until he attained a formalist perfection. And he writes about his exaltation at finally getting it right. Perhaps it’s odd to be identifying with Weston at this point in my life, but I have to admit that my process with the fridge was strangely similar. It involved a slow, methodical deliberation, a stalking of light, of waiting for the precise moment of solar illumination in an otherwise dim room. To get back to your question about the concepts in my work, maybe this comparison to Weston speaks to the idea of ‘slow time’, “the cyclical and durational” that Miwon Kwon mentions in relation to my photographs.

JTD: Tell me about the Copperheads project. How did it come to be?

MD: I had identified ‘money’ as a central issue in my life and wanted to make work that investigated the psychology of money.

JTD: There has been a lot of talk about how you make your own C-prints at a relatively small size, defying current trends in photography. Can you speak about these choices and how the analog media relates to the subject matter and theme of your work?

MD: Generally I find large photographs awkward and ungainly, and actually my preferred mode of viewing photographs is in books. To answer the second part of your question about analog media in relation to my subjects: it’s an aesthetic choice, combined with a familiarity, a certain level of affection and comfort in relation to cameras and materials.

JTD: Can you speak about your interest in everyday objects, including objects that are often overlooked or regarded as a nuisance, such as dust and empty bottles, and how these objects influence your photographs?

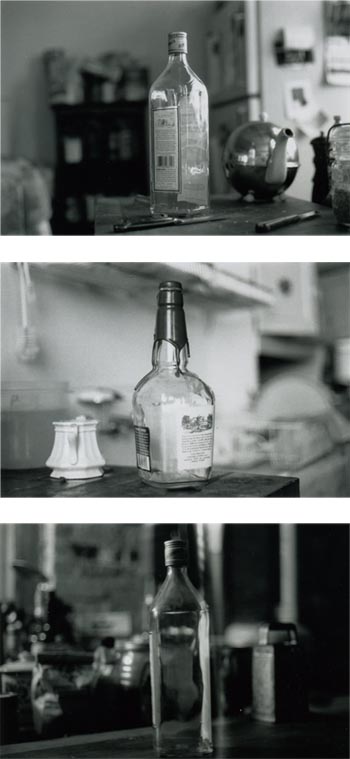

MD: Bottles, especially the clear glass ones, refract light in beautiful and surprising ways. I began the bottle series because of an accident, a blurred Johnny Walker bottle that turned up at the tail end of a B&W contact sheet. I loved the look of it and began to take intentional pictures of empty whiskey bottles consumed in my household, and did this for a period of five years, realizing at the end of this term that the totality of the images constituted a kind of calendar, a finite block of time denoted by the consumption of a particular type of spirits. I followed the B&W series with a color series, also documenting five years of consumption.

JTD: What is your attraction to dust, and what do you believe it conveys to the viewer about human nature?

MD: I’m kind of obsessed with dust as this nuisance substance, and just the whole Sisyphean nature of it that Simone de Beauvoir talks about in relation to the futility of housework, the housewife’s ‘endless, hopeless battle against dust and dirt’. Beauvoir says that the only way out of this trap is to embrace the “life in death” in decay. Dust is made up of dead matter, but it’s also totally alive in its entropic, inescapable fashion. If you can find a way to make your peace with it then you won’t be doomed to “the general and the inessential.”

JTD: Your work also speaks to the passing of time, alluding to this through material evidence. Can you speak about the role time plays in your work?

MD: It’s most evident in some of the domestic interiors, where you see objects, a bookshelf for instance, change over a five-year period, but also the bottle series and of course any of the pictures with dust--Rosalind Krauss says “dust is a kind of physical index for the passage of time”. The idea of time is present in the video image of a stack of diaries (twenty-one years’ worth), and the counting of six years’ worth of shrink bills. One of the main subjects of Fifty Minutes is an interpolation of the notion of nostalgia. The tabletops with books, papers, writing etc. are a way of keeping track of where I was and what I was doing over certain periods of time. There’s definitely a strong diaristic element to those photographs, a need to contain and remember.

JTD: Can you speak about your video work? What function does it serve that still photographs cannot?

MD: Fifty Minutes, my video about psychoanalysis, nostalgia, reading etc., is rooted in writing, and that is the significant difference from still photographs. I get a lot of gratification from writing, I love the immediacy and directness of it, and I love the democratic nature of it. That translates to video as well.

JTD: Though your processes are analog and traditional, in a sense, your relationship to photography seems very contemporary. Do you consider yourself a “photographer”? How do you view your position as an image-maker in relation to other artists?

MD: I write about that in Notes on Photography & Accident, which is published in the catalogue for the show, which is actually more of a book than a traditional monograph-catalogue, which was of course intentional. It’s a very fragmented, hybrid essay, also part diary, but one of the things it addresses is my frustration and boredom with a lot of contemporary photography, the contrived, epic-scaled works that proliferated in the last 10-15 years. It was my impatience with this trend that led me to explore the whole notion of accident and to posit it as the thing that’s gone missing in contemporary work. I do consider myself a photographer, but since I also write and make videos, I usually say ‘artist’ when asked what I do.

JTD: Your writing seems to be an integral part of your art and your ideas. Can you speak about the relation between writing and photography? Do they serve different functions for you, or do they play off of one another to create the ultimate experience?

MD: The many connections between writing and photography, from the very meaning of the word itself (light-writing), are a big part of what the essay tries to explore and tease out. The essay is motivated in part by a wish or fantasy that writing and photography might be the same thing--I read Benjamin, Barthes, Sontag, Krauss and others looking for clues or instances of this cross-over. I do think words and pictures together form a kind of ultimate happiness.

JTD: Where and how do you find your inspiration? What writers and artists inspire you the most?

MD: I read, I graze. I kind of let my attention drift over a wide array of stuff including audio. I’m acutely aware of and fascinated by the act of reading, of when it feels like a heightened, sublime experience, but also when it just seems like mindless consumption akin to the every other form of over-consumption in the culture, when the masses of volumes seem like dead weight. I think the image of blowing dust off my books in the video kind of speaks to that dichotomy. I’m still reading Barthes, Benjamin, Malcolm and Sontag. Last Summer my life was high-jacked by Catherine Lord’s The Summer of Her Baldness and now I’ll read anything by her.

JTD: What are you currently working on, and what is next?

MD: My next project will be a video, and it will begin with something that Walter Benjamin wrote about a view of a clock.

- Moyra Davey, Bottles, 1996-2000

- Moyra Davey, Glad, Chromogenic Print, 1999

- Moyra Davey, Dust floor, Chromogenic Print, 2007

Long Life Cool White - Fogg Art Museum

"Long Life Cool White" is on view until June 30th at the Fogg Art Museum, located on the Harvard University Campus at 32 Quincy St. in Cambridge.

All images are courtesy of the artist and Harvard University Art Museums.