One goes always upwards for the sake of this Beauty, starting out from beautiful things and using them like rising stairs.

- Plato, Symposium, 211c

We all need to transcend sometimes. The boring. The chaotic. The painful. Transcending the finite has often been thought of as a purpose — even the main purpose — of art and beauty. Evocations by Greg Lookerse gives us a renewed opportunity, which is becoming increasingly uncommon, to explore that idea. That is a bold concept in an age regularly celebrating the banal. Yet ancient and contemporary philosophers have continued to explore and promote this kind of aesthetic transcendence of the quotidian.

This article is the first in a series connecting philosophy and art to investigate the many foundational theories of art that have been proposed throughout history and whose influences can still be seen in even the most contemporary creations. Evocations is a fertile exhibition for discussing Plato’s mimesis theory of art, which claims that all art is an imitation that can help guide the way toward a higher, perhaps even ultimate, reality.

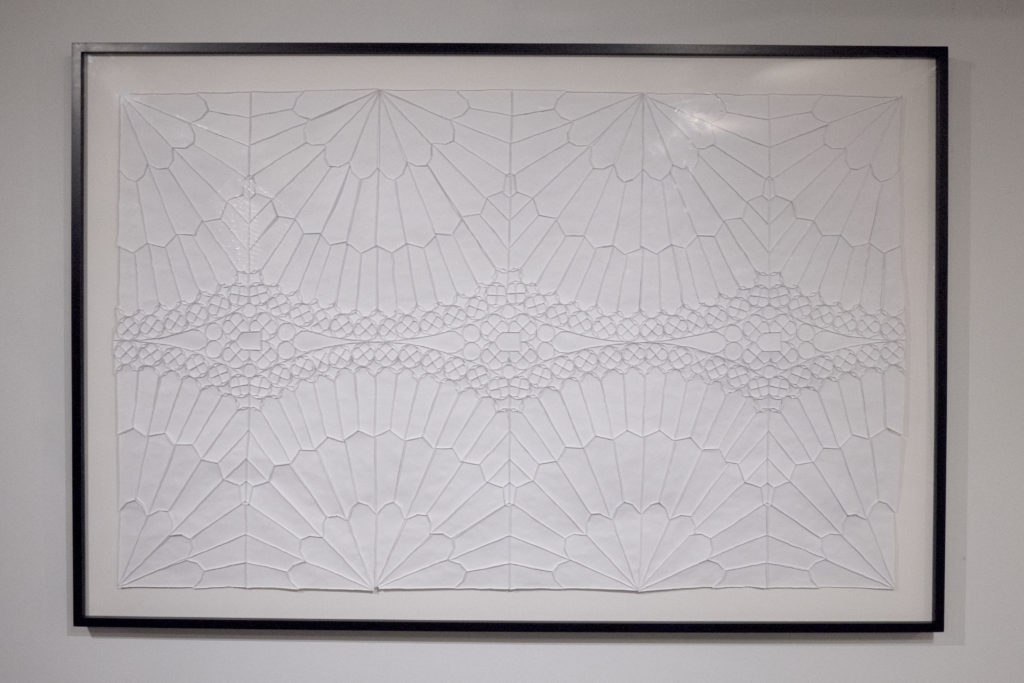

In this exhibition at AREA, Lookerse, through papers collected together as puzzles, brings a symmetrical beauty to the fore. The folded tabs at the edges of the individual papers, fencing in the different shapes, join to create the Firmament series. About four by six feet, the pattern of the arranged papers was inspired by the ceilings of cathedral and chapel naves.¹ However, in their position on the wall, the seemingly simple designs suggest stained glass windows without their luminous color. While they might look like empty spaces awaiting a meaningful addition, these opaque windows nudge the beholder to reflect on an inner light. During the bright light of the day, you can see the patterns getting lost in your reflection.

The stark white papers are divided into compositions through the folded sides, creating shadows. This repetition of shapes helps to set a slower pace, more suited toward contemplation. When we keep too busy or experience busy things, we can fail to have any kind of meaningful or long-lasting reflection. Disorder is a hindrance, but harmony, exemplified in these works, is an aid to our contemplative life. The structure and composition of these works are catalysts for self-reflection as your eyes follow the orderly movement of lines.

Mimesis means imitation. For Plato, the things we see in our world are just representations or shadows of their perfect forms in another realm: Reality. An artist creates another representation of the representation, like Lookerse’s imitation cathedral ceilings, which further removes it from Reality. But does mere imitation qualify for art? Plato thought that art should direct people toward this ideal Reality, and art that failed in this respect should be banished.

If, according to Plato, physical beauty guides us to true beauty, we may wonder what he considered beautiful. Proportion, particularly symmetry, was a strong condition of beauty. So strong, in fact, that at least five hundred years after Plato, the philosopher Plotinus made a point to claim that symmetry could not be the sole attribute of beauty.² Nevertheless, proportion — or its types, like symmetry and harmony — was clearly important, and still is now.

Firmament #1. Cut and Folded Paper. Photograph courtesy of Janee Lookerse.

The symmetry and monochrome palette of Firmaments allow one to relax and be consumed by the beautiful delicacy of these works. Our current time is highly troubled, and Lookerse places order without monotony into our path. The orderliness of these works might lead us to contemplate the existence of a higher order as we project the structure before us onto our own existence.

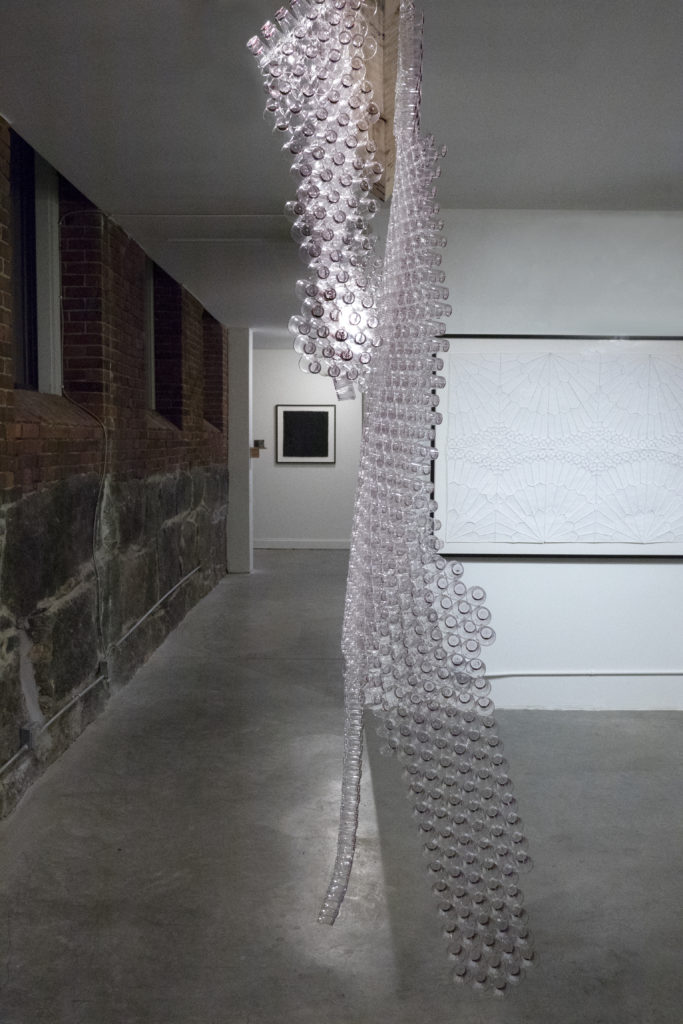

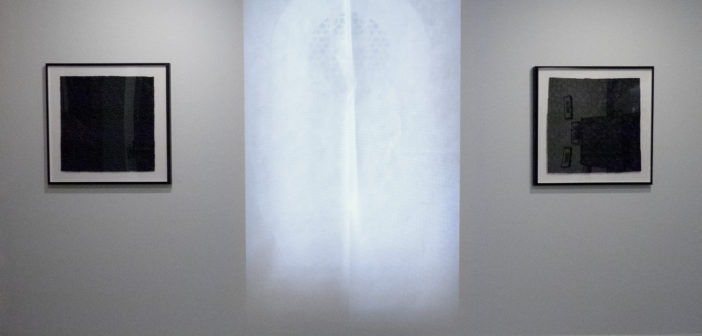

Lookerse explores the tension between life and death in some of his other pieces, such as the Altar Stone series. These stones are grouped into two clusters in the gallery, and have holes filled with honey and charcoal, juxtaposing life and death. Additionally, he presents the silhouette of a lion skin draped over a rack made from small plastic communion cups, called The Lion Skin of Judah. All his work, according to the artist’s statement, has an “intrinsic touch of religious connotation.” Appropriately, each piece that makes up Evocations, though in many ways unassuming, begs for us to look to something deeper and beyond our immediate perceptions and individual frameworks.

The Lion Skin of Judah. Plastic Cups, Glue, Dried Wine, Wood, Rope. Photograph courtesy of Janee Lookerse.

How and why is Lookerse using such overt religious imagery? His work is founded upon order and harmony, the innate calmness of which gives us a chance to pause. As Kierkegaard writes, “For pausing is not a sluggish repose. Pausing is also movement. It is the inward movement of the heart. To pause is to deepen oneself in inwardness. But merely going further is to go straight in the direction of superficiality.”³ Perhaps Lookerse is exploring the nature of contemplation as a means of discovery about ourselves and others, and is using a fairly accessible set of images and symbols to guide us along with him.

Contemplation as an act was an important concept in medieval theology and philosophy. Regardless of Lookerse’s metaphysical commitments here, his work at least tempts the viewers to engage in the act, which is suggested by the kneelers that anyone familiar with church furniture will grasp. Using the kneelers forces the viewers to sit lower than the works, forcing them to look up. Similar to the way that cathedral ceilings strike viewers with sublime feelings of the divine, the Firmament series propels us to look beyond what we can see with our physical eyes, inspiring the transcendence that is often associated with religion.

Reflection and contemplation give us necessary relief from life. Plato, in the Laws (653d), mentions that the gods took pity on the human race because they were born to suffer. The periods of repose and contemplation made them whole again for their labors, which enabled them to continue laboring until their next moment of reflection. In the quiet reflection, we confront our human nature, for better or worse, and our way to fit within the cosmos. These representations of order offer up some hope that maybe—just maybe—there is some order to the world. The rocks we endlessly roll up the hill might have some purpose beyond our immediate actions.

Subscribing to Plato’s theory of mimesis could inform our understanding of art such as Lookerse’s. Looking to what a work of art imitates, whether a tangible subject or something more conceptual, can provide a key to understanding the particular work we are beholding. For this exhibit, we could consider whether these works contain a beauty that can point us toward the higher understanding of beauty found in Reality.

Lookerse's overt references to religious themes, practices, and architectural structures are an imitation that compels toward transcendence instead of mere replication, offering us a chance to experiment with Plato’s idea of transcendent and directional beauty.

Evocations is on view at AREA Gallery until March 9th. More information can be found here.

¹Email with artist

²Plotinus, Enneads, I.6.1.

³Søren Kierkegaard, Purity of Heart is to Will One Thing, translated by Douglas V. Steere (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1948): 217-218.

3 Comments

Brilliant review! As someone who gravitates toward “Order without monotony” and finds symmetry calming, I’m appreciating Lookerse’s elegant work.

Pingback: Mini-Heap - Daily Nous

Thank the (Greek) gods someone is digging in and employing humanistic philosophy and aesthetics to bridge art and audience instead of relying on tired tropes and the trappings of “theory.” The idea behind “order without monotony” is interesting. I suppose Mondrian, too, employs order without monotony for spiritual ends, though it’s of a different kind than Lookerse’s “Firmament.” Agnes Martin might be the ultimate example of the kind of “order without monotony” you’re talking about, given the crucial variations and flaws that result from her having drawn all those ordered graphite grid-lines by hand. More writing like this please!