Slip the straps of the eight-pound backpack over your shoulders, buckle it around your waist, and try not to tense up as an attendant tightens your virtual-reality headset. In a moment, the large, mostly empty room at the MIT Museum is gone. You’ve entered The Enemy, an immersive, interactive exhibition developed by photojournalist Karim Ben Khelifa in collaboration with MIT professor of digital media D. Fox Harrell. Take a tentative step into the first of its three white-walled galleries, each dedicated to a different combat zone: the Democratic Republic of the Congo, El Salvador, and Israel and Palestine. Photographs of two combatants from opposing factions wait on opposite walls. Step toward the photos, and a narrator’s voice introduces the two men. Then, before you’ve fully acclimated to the weight of your gear or the contours of this virtual space, the two men suddenly walk into the room.

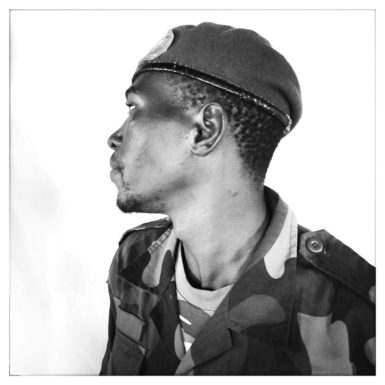

You can hear their footfalls, watch the camouflage of a uniform crinkle as a soldier gestures, and even scrutinize the tattoos on the men from El Salvador—one with intricate sleeves and an insignia of MS-13 inked across his forehead, the other with tribute to his wife on his side and an homage to his gang, Barrio 18, over this heart. A voice poses questions to each man as he stands in front of his portrait. What is your first memory of violence? What does peace mean to you? Who is your enemy? Have you killed an enemy? What is happiness for you? Where would you like to see yourself in 20 years? What do you fear?

Photo courtesy of Karim Ben Khelifa.

Each of the six men answers these questions and others in his native language, a translation echoing after. A former child soldier from the Congo recounts killing nine people at age 14, three years after his own parents were murdered in front of him, their brains splattered across his skin. A gang member who has spent 17 years in prison recalls the beatings he suffered at the hands of his parents and the first time his daughter called him papa. A Palestinian hopes for peace among his people, and with his enemy, too. He wears a balaclava to conceal his identity from both. It covers everything but his eyes, which follow you, even when you move to the side.

The men’s movements were captured by 3-D scans in makeshift studios in each location, then painstakingly pieced back together with recordings of their interviews at Ben Khelifa’s home base in Paris. Before long you realize your body language, too, is being monitored. These reactions, and the results of a pre-exhibit questionnaire, shape what you see in the galleries and in a fourth, final room, whose contents I’ll leave for you to discover. Afterward, once an attendant has helped you out of your gear, you can take a seat and read some background on the project as you readjust to reality. It might be useful, at this point, to learn more about exactly how the data from participants’ questionnaires and movements are interpreted and deployed. But that omission doesn’t undercut the power of these stories, brought to life through a technology often used for escape and entertainment, here transformed into a conduit for encounters with people half a world away.

Ben Khelifa, who has trained his lens on subjects in more than 80 countries, including Iraq and Afghanistan, says he was motivated in part by frustration with the limits of war photography and its power to produce real change. Interestingly, this project, which evolved during his artist residency at MIT’s Open Documentary Lab, was initially conceived as a photography exhibition. How might the effect of The Enemy be different if it was a photography exhibition? A photo essay in a glossy magazine? A video installation? A documentary film? An app? (In fact, a free augmented-reality app allows users to experience elements of the exhibition through their smartphones).

Photos courtesy of Karim Ben Khelifa.

These images and testimonies would pack an emotional punch in all the aforementioned mediums, but the virtual-reality experience lends a visceral immediacy that leaves you wishing everyone with an enemy had such a chance to see the specificity of his suffering and hear the humanity in his hopes and dreams. Even silences carry weight: When one man leaves a pointed question unanswered, when you hear only the sound of his breathing and your own, you feel the tension of that moment in a way the wall text of a conventional exhibit likely could not capture. Though this novel medium limits the work’s reach in one practical sense (only five visitors are admitted per quarter hour), it also allows Ben Khelifa and his collaborators to intrigue many who might skip past a headline about the Congo. And if you choose to meet face-to-face with these men — who each close with the words “Thank you for listening” — I suspect their voices will resonate long after you step back out into the sunshine.

The Enemy will be on display at the MIT Museum through December 31. Visit the exhibition's site for entry times and registration details.

1 Comment

Your powerful description of this experience has made me want to take part in it. Thank you so much.