Gallery Director Deborah Davidson’s We Dream | Beauty Beyond and Beneath gathers together an ensemble of artists to present visions of beauty broad in scope and varied in manifestation. The group is comprised of professional artists who are represented by various Boston galleries — Gallery NAGA and Kayafas, to name a couple — and are the first group to be featured in Suffolk University’s new gallery space. Using their own visual languages and media, they portray the relative nature of beauty and our personally subjective and historically inherited ways of constructing our own definitions of it.

Beauty, of course, is a fraught term for artists and their viewers alike. Art historians, philosophers, and cultural laymen of all creeds have their own definitions and criteria of what constitutes beauty, ranging from the verbose to the platitudinous. Beauty does not exist in a vacuum. The words we use to describe beauty and the images of it that we perpetuate all form a vast, pervasive social construct that is increasingly difficult to contend with.

Pragmatically, guidance for the gallery visitor is provided in the form of Exercises for the Quiet Eye, a series of open-ended questions and viewing techniques. Developed by Annie Storr, an art historian and museum educator, these exercises encourage viewers to embrace ambiguity and to temper their urges to reach a singular, static interpretation of the artwork before them. Echoing her ideas are three writing prompts listed near the gallery’s entrance, to be applied to any and each artwork that the viewer considers: What’s going on in this picture? What do you see that makes you say that? What more can you find? Patience is key; answering all three questions with each work takes time.

The range and depth of the artists’ interpretations of beauty are immediately apparent. The diversity of work on display can give rise to innumerable answers to Storr’s aforementioned questions. Many pieces do not conform to the archetypal Western canon of beauty. Other works take initial repulsion a step further, offering grotesqueries, seeming desecrations of the human form itself.

Eden, Mammae. Image courtesy of Tabitha Vevers.

Tabitha Vevers’ works of oil on Mylar beg for more nuanced inspection of the notion of beauty. Eden, Mammae depicts a stolid figure with a protruding skull. The main maternal figure lacks arms, and has an odd number of legs, but seems serene in her stature. Infants crawl over her many breasts and struggle to wrest a diaphanous cloth from her feet. All stand in the glow of a gold-leaf backdrop upon a sandy shore. What beauty is there to be found in this malformed figure? It depends on how concrete the viewer desires to be with their definition.

Comparisons to the ubiquitous influence of Classical statuary are quick to follow. Botticelli’s Birth of Venus comes to mind, both because of the pale and calm feminine figure and the small bivalve in the lower right register. With Storr’s guidance, one can deeply contend with externally defined concepts of beauty. To those who value symmetry and order, the maternal figure is bound to offend; such symmetry is pervasively delivered in today’s digital advertisements. From this perspective, the extra breasts are deformations. However, they also create a figure of plenty- one who can breastfeed all her children comfortably and abundantly, calling to mind non-contemporary icons of fertility and beauty.

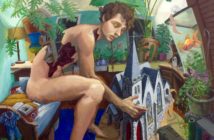

Geisha. Image courtesy of Emily Eveleth.

Emily Eveleth’s paintings of doughnuts and pastries also delve into the tension between what is considered beautiful and our physical needs and desires. Lit from the bottom, the sweets are stacked in a lop-sided tower, icing oozing down to their base and sinking under the girth of their sweetness. As a peckish art consumer, however, my gaze inadvertently transformed them into objects of acute longing.

In a devastatingly image-conscious culture, where our socially reinforced impulse to look our best is at odds with the realities of our bodies, these confections can represent stifled desires that are seemingly in complete opposition with our efforts to fit into a certain mold. We should not want these sweets — they are the archetype of “bad” and “empty” calories. And yet, their sensuous presentation gives them a majesty and intrigue that creates desire. When discussing a concept as enormous as beauty, presenting the seeming antithesis of attaining beauty poses fecund questions about what exactly it is that we have been taught to long for.

Byzantium. Image courtesy of Robert Lewis.

These thoughts on beauty shift and change as more time is spent with the works. Robert Lewis’ Byzantium ties together these themes of time, nuance, and the constructed nature of an ideal. A bust of a woman, reminiscent again of Classical sculpture, towers above an arena of brick and building supplies, evoking industrial sites. Whether the figure is being built up or demolished is ambiguous; regardless, the bust is in a state of flux. We can imagine the bricks falling one by one to become scattered detritus along the base, or getting raised up to build and reinforce the face. Resolution can never be reached, and so this figure will always be subject to the ebb and flow of industrious social construction. Whether one can call the result beautiful depends on the angle of interpretation, and I found myself constructing narratives flowing multiple ways.

In addition to Storr’s guiding questions, another gallery tool has been included to demonstrate the power of patience: a camera obscura room. It is installed near a grouping of pinhole photographs by artist Jesseca Ferguson. The visitor is encouraged to step in and to wait for the small pinhole at the opposite side to deliver an image. After adjusting to the dark, a series of lines, formed by the shadows of the extensive scaffolding outdoors, filters into the space and stretches onto the opposite wall. My guide expressed minor frustration that the construction was obstructing the image. I found the external realities of the building’s renovation to be equally as enticing. Like Lewis’ sculpture, the camera obscura chamber captures the site’s renovation, where greater sturdiness provides the foundation for ornamentation. Likewise, Byzantium retains its visually arresting — yet productive — chaos. Finding space for thought in that chaos is both an effort and a prize, fruit found throughout the exhibit. In that frozen moment something else emerges altogether — satisfaction.

The Suffolk University Art Gallery is free and open to the public on weekdays from 11-4 p.m. and by appointment. We Dream | Beauty Beyond and Beneath is open until Friday, October 27th.