The Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts includes two remarkable paintings by the French Pompier or Academic/ Salon painter, Jean-Leon Gerome (1824-1904). A student of Paul Delaroche he traveled to Turkey in 1854 and to Egypt in 1857. Inspired by these travels and time in North African, French colonies he added the theme of Orientalism to his work which also included illustrative pot boilers, and crowd pleasers, based on the more gory aspects of Roman history as well as glimpses of the glory days of France. In views of exotic and erotic North African life he followed in the tradition of Ingres and Delacroix. He depicted similar scenes but never enjoyed the status and fame of those masters.

But if feminists and art theorists have their way, that may change. Where Gerome may have slipped into the dust bin of history as a minor, anecdotal, salon painter, he is given pride of place in articles that slice and dice issues of colonialism, racism, sexism and Eurocentric bashing of Islamic people and culture. It always amuses to see Gerome lavishly illustrated in yet another strident article in Art in America. While Gerome is held up as the worst possible example of everything that was oh so wrong in 19th century French culture, time and again, one comes away thinking (file under guilty pleasure) that Gerome was a pretty nifty painter.

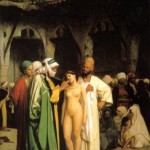

If imitation is the sincerest form of flattery the four recent paintings by Moroccan born, Saudi citizen, Lalla Essaydi, on view through May 14 in the Williams College Museum of Art, may have quite a different impact than the artist intends. For this occasion the museum has borrowed Gerome’s small, daunting, mesmerizing, meticulously painted, jewel like, but horrific and repulsive “The Slave Market.” It depicts a robed and hooded North African man inspecting the teeth of a nude slave woman (devoid of public hair as was the convention of the time) being offered for sale by a gesticulating merchant. Her head is tilted by the pressure of his hand forcing open her mouth for the inspection of a buyer evaluating her age and health like a beast of burden. It is the ultimate humiliation of a woman. She is a sexual commodity to be bought and sold for the pleasure of the intent potential buyer. Unlike the paintings of Ingres, however, this slave woman or sex worker, at least looks ethnically correct. Ingres often gave his Odalisques distinctly European features the better to encourage the fantasy of the erotic male gaze.

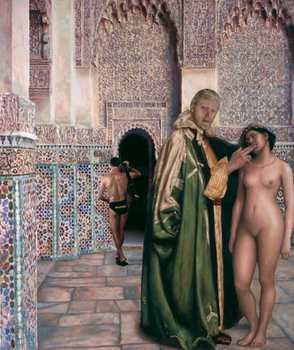

The scene takes place in a courtyard and in the background; huddled on the ground are a group of women and children, presumably, to be sold. Essaydi has enlarged and modified Gerome’s painting. The background and other “slaves” have been eliminated replaced by what now has more distinctly Islamic architectural detail. While the “buyer” is wearing the same robe and is seen in profile, as he examines her teeth, he also turns and looks out at us. The surprise is that he is not disguised and hooded as was the original man. Instead he is clearly white with blue eyes and even has spiky, short, dirty blonde hair. He looks like a contestant on some reality TV show. In the thesis of the artist the white male is confronting us. He is the surrogate or signifier of the intended viewer pandered to by Gerome. Arguably, he painted for the pleasure of the randy French male viewer and collector.

Of course the really disturbing aspect of this, and presumably Essaydi’s point, is that the despicable painting was quite accepted in the context of the salon exhibitions precisely because the protagonists of the work were not, for heavens sake, God fearing, church going, French Catholics. No, the painting represented a glimpse of the life of the Other. In this instance the Islamic subjects of the French Empire. Like Ingres and Delacroix before him Gerome was exploiting French fascination with the custom that Koran permits a man to have up to four wives. And that the culture allowed for the acquisition of concubines or odalisques gathered into harems. French artists spilled a lot of paint on canvas playing to that aspect of erotic imagination. Of course, Gerome’s paintings illustrate the worst aspects of colonialism, racism and sexism.

Which is Essaydi’s point. Gerome delivers rich and provocative, reprehensible examples for polemical arguments. The Clark also own his magnificent but troubling “The Snake Charmer” which features a nude boy, holding an enormous boa, before the drooling and leering gaze of a group of men seated next to a sheik. It reeks of pedophilia. But, again, it is absolutely deliciously painted, particularly the light shimmering and glimmering off of the wall tiles in the background. It is precisely in these aspects of craft and execution that Essaydi is most wanting. Her deconstruction of the content of Gerome evokes none of his exquisite technical mastery. To see her four works in the same context with just one of his paintings, however deplorable in subject matter, is just disarming. We want her surfaces to be as magical, seductive and sparkling as his but they are simply not.

And Essaydi may be advised to tread a bit more lightly. In her appropriation/ deconstruction of “The Slave Market” which she titles “Duty Free” (what does that mean?) there is a figure of her invention proceeding to the left in the perspective space. The male figure, seen from the rear, is a “bather” in black briefs. He is walking toward an arched doorway. On his ass is clearly written “Sea World.” It is annoying and distracting. Why has the artist worked so hard to convey the exotic mood and intensity of the painting just to screw it up with a cartoonish cheap shot? What’s that about?

The other three works, though absorbing and fascinating, have similar tropes and distractions. While “Duty Free” includes a literal copy of the original Gerome nude woman, the “Odalisques” in the other three paintings, two standing and one reclining, are all images of contemporary transgendered individuals. These “women” with breasts, pretty faces, and attractive figures, also have male genitals. Is her intention to punish and embarrass our smarmy “male gaze?” Just what is this fixation in her work that has been played out over the past several years starting with a well know model she worked with at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts? Beyond shock value just what is the point? In each of the three paintings the nudes are accompanied by a witness or individual in ethnic dress. They range from young boy to middle aged woman. As we look at the nudes, who boldly look back at us, the witnesses also turn and confront us. So a dominating theme is exposure, vulnerability, voyeurism and confrontation. In the large painting “Arab-Esque” the reclining figure is accompanied by a colorfully costumed seated woman who looks at us, glancing up from reading a coffee table book on Islamic art. Is the artist playing here on her own complex cultural identity as an Islamic woman from a repressive traditional background who has broken out by living and working in a Western environment? Indeed, while Koran forbids the Graven Image, she has learned to paint the figure at the Museum School. That must surely be a paradox.

There is much to respect and admire about Essaydi and her work. She is intensely dedicated and hard working. Her skill in painting is improvingly dramatically with each new exhibition. She may indeed one day be on a level playing field with the techniques of the salon. But, until then, these send ups and deconstructions will remain forced and unresolved. If anything, her reprimands, added to scolding articles in major art publications, a cottage industry, make me long for a full scale retrospective of Gerome. He may be one of the most interesting of the formerly downgraded and disgraced academic painters. The Clarks liked him during a time when it was less fashionable, and cheaper, to do so. Gerome is creeping back into the canon of art history. For example, there is a color illustration “L’Eminence Grise” (1874, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) in the text “19th Century Art” by Robert Rosenblum and H.W. Janson. There are major works by the artist in numerous American collections. We have all at one time or another in history textbooks gazed upon his “Pollice Verso” (1872, Phoenix Art Museum) which popularized the “thumbs down” ritual of Roman gladiator contests. Some day I would love to feast my eyes on this iconic text book illustration. And while Essaydi fixated on Gerome’s “The Slave Market” just how would she respond to his “Slave Auction” in the Hermitage which presents the same theme but from the perspective of ancient Rome?

So while the artist has labored long and hard to expose the dark side of the Clark’s nasty little picture, it has encouraged us to long for Gerome. Show us more of the bad boy of 19th century academic painting. Odds are it would make for boffo box office.

Links:

Williams College Museum of Art

"Transgressions: Lalla Essaydi Confronts Jean-Leon Gerome" is on view January 14 through May 14 at The Williams College Museum of Art.

Artist lecture and opening February 9.

All images are courtesy of the artist and Williams College Museum of Art.