If you ever have the pleasure of meeting the fascinating Magda Fernández, you will be encapsulated by her engaging ways of storytelling, kindness, and laughter. Her work is brilliant, raw, captivating, hard to watch, and yet very intriguing. Her way of thinking and building narratives is unlike any other artist I’ve seen. Blurring the line between theater and performance, Fernández’s images pierce through your core and ask you to question your own history. “To eliminate racism, you have to look at your own family history of racism, acknowledge that you were born into that, and make sure that you’re not repeating those horrors. It means looking at your ancestral past,” Fernández says. Although silent, her heavy videos on family history and legacies will leave the loudest echo in your mind. This is the time to support women who do not fit the art world norm.

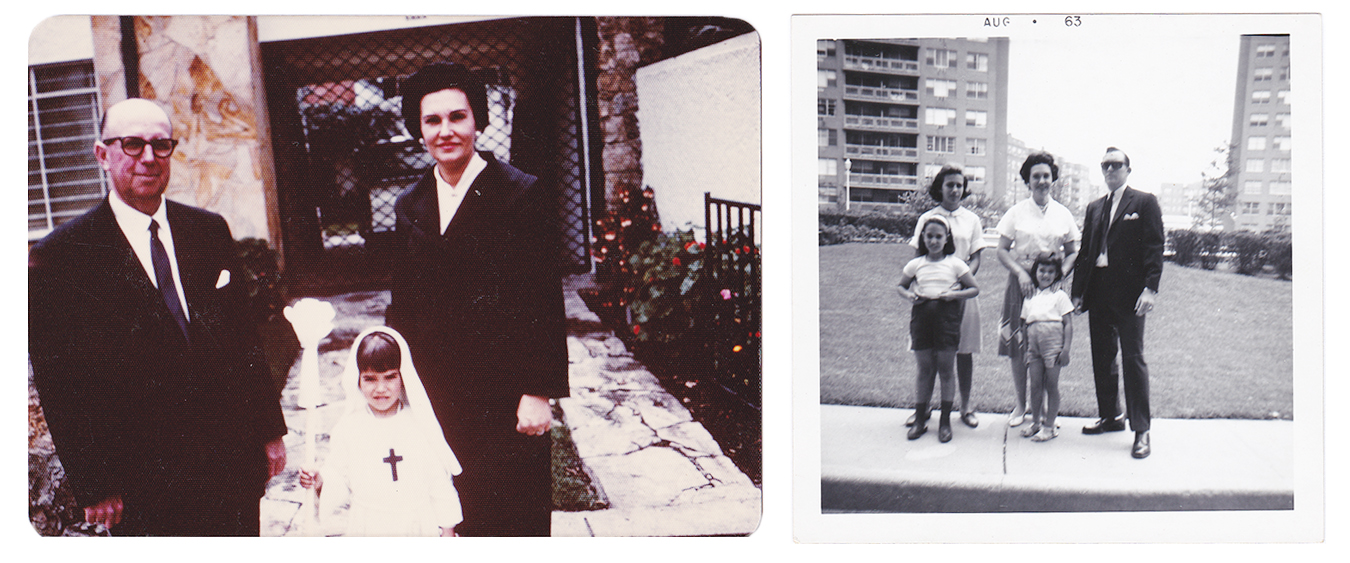

Fernández with family in Colombia, Bogotá (left) and Queens, NY (right)

Silvi Naci: There is a lot of history and research behind your work, driven by passion to understand and uncover your family’s legacy. Let’s start when you left Cuba in 1961. You were only three years old. Can you talk about your experience, roots, and family dynamics that are very present in your work?

Magda Fernández: I was born in 1957 in Havana, Cuba, but have lived in the United States since 1962. With all family memorabilia left behind, I’ve known very little about our family’s past other than what I was told, that my parents were first-generation Cubans and earlier generations were from Spain. But my own genealogical research and DNA test reveal a lot more.

On my mother’s side, records show that I actually come from a long line of Spanish families that colonized Cuba and remained on the island for generations until the Revolution. My maternal DNA indicates that between 1690-1780 we also have Amerindian and West African ancestors. This discovery – that my ancestors had a hand in establishing Cuba’s long and ruthless colonial rule – shook me to the bone. Anyone with any sense of humanity should understand why. We’re talking about a hard line, a colonial system that annihilated Cuba’s indigenous Taínos and existed as a slave society for 400 years! Given the circumstances, I strongly suspect that my Amerindian and West African ancestry was borne out of coercion. I need to access Cuba’s Puerto Principe colonial records to find [my ancestor’s names], which is no easy feat. As disturbing as these discoveries are, they explain a lot of things about my family that have pained and confounded me for much of my life. These revelations and feelings are the focus of my videos about my Cuban roots.

My parents chose to flee Cuba because Castro began to close the Catholic churches and send bourgeois children to re-education camps as part of the literacy and agrarian reform campaigns. There was a real utopian effort to uplift the entire Cuban country and dissolve the pre-existing class system. These things, plus the specter of communism, terrified my family. With the assistance of the church leadership, my parents secured visas for us out of the country. After staying with relatives in Bogota, Colombia, for a spell, we settled in Queens, NY. My teenage brother, however, participated in the failed CIA-sponsored Bay of Pigs insurrection. He was held as a prisoner-of-war in Cuba for several years, and never recovered from his treatment there.

Given all these things, I grew up associating Cuba with trauma. To my parents, their Cuba was a white man’s paradise that was obliterated forever. They missed their social institutions and lifestyle that kept the classes and races apart. As far as they were concerned, Spanish colonialism “civilized” their tiny island nation. They were despondent over their loss and never adjusted to life in the States.

I, on the other hand, never identified with my parents’ conservative views. My mother especially was wildly authoritarian, so debating or questioning anything was never allowed in the home. My parochial school education was equally rigid. College was the intellectual lifeline that allowed me to emerge as my own person. But this came at a price. My mother so disapproved of my opposing beliefs that she basically shunned me for the rest of her life.

From my early education all the way through high school, I had been pegged as class artist due to my drawing skills. This made me question whether this art identity was just another forced expectation. I abandoned art and studied critical social theory instead to make sense of my very confusing upbringing. It wasn’t until my thirties that I returned to creating art, and I haven’t stopped since.

SN: I am curious in the journey that brought you back to Cuba as an adult in 2016. You speak of this experience with such great joy and have told me you felt a great sense of embrace by the Cuban people. Will you talk about being back and what this trip has brought up in you?

MF: By the time I reached my twenties, I walked away from the family drama and buried any thought of Cuba. There was one opportunity to go back with a college study group, but given my family’s history, the Cuban government said they would welcome me back as long as I submitted indefinitely to a reeducation camp. I declined, because I wanted to travel on my own terms. After that, I assumed I’d never be able to go back because of the family stigma.

Twenty-nine years later, I found myself revisiting the idea of returning when news broke that Fidel had stepped down, and finally, last year I was able to visit for three weeks. It was one of the most profound, liberating experiences of my life. In this place, I was not a “spic” or a “wetback” as I frequently was called while growing up in Queens. For the first time that I can recall, I was not an “other.” I did worry that the Cubans on the island would just write me off as an American, but in the contrary, to the Cubans I met, I was cubana – Eres cubana, pero eres familia (You are Cuban, you are family).. These are all complications and distortions that occur with displacement, and you just have to sort through the thicket, one step at a time.

SN: The impact of tierra (earth), nationalism, and a sense of belonging is clearly apparent in your work querida cuba (2017). It is also the first video that utilizes real footage you took in Cuba in 2016. Can you talk about this piece, your process, and love for dear Cuba?

MF: In my previous Cuba videos, I had to use found footage or footage I took of other places to represent Cuba. But not this time. querida cuba (2107) is a love letter to my homeland. It’s a complicated love, one that I’m still trying to understand. What I do know is that I’ve never felt this way about a place before, and realize that all these years, I’ve been incomplete without it. I constantly yearn to revisit Cuba. This video asks, what exactly does it mean to be a Cuban? It’s a vexing question for individuals like myself who have lived elsewhere because of forced immigration.

What struck me so much when I was in Cuba was la tierra, the earthly cornucopia that is Cuba. The tierra in Cuba is also the site of 400 years of colonial oppression. I see la tierra as a witness to the history that I am trying to dig out. In querida cuba (2017), the old Cuban stamps on my face signal that I am traveling into that ancestral past for answers. Stamps also are interesting documents of a country’s utopian ideals at a moment in time. There was one old Cuban stamp that struck me the most, and states: Todas las razas caben en America – meaning, All the races fit in America.

Magda Fernández, Still from querida cuba (2017).

SN: How do you start a video work? Is it through writing, an image, or an idea? What is your process of creating a narrative, even though they are not linear?

MF: It starts with a question that is important to me, which appears to have no answer. I then start researching that subject deeply, which generates all sorts of images, insights, and emotions – which in turn become the material of my videos. I usually videotape the backdrops first and put together a rough edit. In the process, I formulate a general idea of the performances I have in mind. The next phase involves assembling my props, which can be very time-consuming, but incredibly fascinating. Once I have all those pieces together, I set up my green screen studio and shoot the performance over a couple of long days. The performance is both roughly scripted and improvised. Some of the footage is usable and some is not. The video truly starts taking shape during the editing process, which takes at least six months to complete.

SN: You once had a studio visit with Joan Jonas. What was the criticism she made that changed your way of making videos?

MF: When I first started working with video, it never occurred to me not to use sound. Ute Meta Bauer, who had seen my videos, insisted that I show Joan Jonas my work. Although Joan said positive things about my visuals, she cautioned that the Philip Glass music in one video made it come across like a borderline music video. I came to realize that she was right.

Magda Fernández. The colonial curse: La padrona and progeny, La Madama (a Cuban spirit doll), and El Maquetauri Guayaba (Lord of the Dead). Still from colonial blindness (2011-2015).

What I have found since is that the absence of sound compels me to sharpen my imagery. You can do a lot with objects, gestures, placement, size, color, form, and composition to convey anything from a power relationship to apathy. The silent moving image is the language I prefer to communicate with my viewer.

Magda Fernández, Still from querida cuba (2017).

SN: The materials you choose to use in your performances are filled with meaning, cultural references, and symbolism – the earth elements, coffee, sugar, the spirit doll as a symbol of power – can you talk about the meaning behind them?

MF: Symbols are the “words” of my visual language. In querida cuba (2017), the sugar, coffee, orchids, yucca – all things that are extracted from the Cuban tierra – represent Cuba’s physical identity. Some of these physical objects, such as sugar, coffee, and the ceiba tree embody a fraught history. For example, the ceiba tree was a sacred deity to many African slaves during their captivity, and continues to be to Cubans who practice Santería today. In querida cuba (2017), the tree is not only a vessel of those prayers but also a witness to all the violence that has occurred in Cuba’s fields over 400 years. The ceiba has seen and heard things that nobody should ever witness.

In colonial blindness (2011-2015), Queen Isabella I of Spain and my mother enact Cuba’s colonial contract. It is a cautionary tale of the colonial mindset’s long reach and a condemnation of my ancestors’ participation. I perform as both women in this work. The props in this video represent the terms of the exchange and the people who were harmed by this arrangement – the Taínos and transplanted African slaves. A cluster of clay Taíno Zemis (ancestral spirits) and a gold-plated Maquetaurie Guayaba (Lord of the Dead) represent the Taínos, and a Cuban Madama spirit doll speaks for the captive African and Afro-Cuban slaves. After much research, I purposely chose these figurines because each one is a respected object of tremendous agency in each culture, and is used ritualistically in response to terrible events. It is important to point out that, although La Madama resembles the racist American mammy doll, she absolutely is an entirely different symbol in Cuba’s culture. There is just no way to sugarcoat Cuba’s colonial contract – it was an ugly quid pro quo. You should squirm when you view the scene with the white padrona on the rock, La Madama, and the Maquetaurie Guayaba. The whole business was nasty, it was wrong, and my ancestors who participated in it were wrong. After connecting these dots, I finally understand why my parents were who they were, and why we were doomed to clash.

Magda Fernández, Taíno Zemis. Still from colonial blindness (2011-2015).

SN: You take on many personas in your work – how do you work with this idea of stepping into someone else's shoes?

MF: Performing as people that I disagree with forces me to try to see the world from their point of view. It forces me to humanize them, even in light of our differences.

SN: Ode to art curator, critic and art historian Hans Ulrich Obrist – Are there any utopian projects that you haven’t yet been able to carry out?

MF: Yes! I need to return to Cuba to conduct further research about my ancestors. I need to comb primary records, newspapers, burial grounds, and ruins. Heaven knows when I’ll be able to realize that.

Magda Fernandez (b. 1957, Havana, Cuba) is a Boston-based video artist who creates art about social issues and her Cuban roots. Blurring theater and performance, Fernández makes silent, diaristic videos that revolve around the duality of themes such as power, helplessness, fantasy, reality, memory and history. Fernandez’s videos were exhibited in "latinx@americanaza" at Samson in Boston, and in "La Cubana y El Cubano" at the Copley Society in Boston. In 2010 Fernandez presented her videos-in-progress at Uta Meta Bauer and Joan Jonas' Art, Culture, and Technology Lectures Series: "The Theatrical/The Performative/The Transformative" at MIT. Fernandez has received grants from the Council for the Arts at MIT, and was a past finalist for both the Cintas Foundation Fellowship and Creative Capital Visual Arts Grant.

To learn more about Magda Fernandez please visit: www.magdafernandez.com and vimeo.com/magdafernandez