“There is both capricious absurdity and poetic impossibility in the realm of the unconscious lapses of time that constitute dreams.”[1]

-Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons

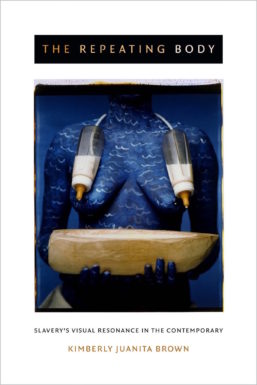

Kimberley Juanita Brown, "The Repeating Body: Slavery's Visual Resonance in the Contemporary," Duke University Press, 2015.

While I reflect upon the indeterminacy of global political conditions, I continue to be buoyed by the power and agency of collective action. Two such examples of building community with fellow artists, thinkers, curators, writers, and scholars have materialized for me in the form of work by The Dark Room: Race and Visual Culture Faculty Seminar, and the #BlackGirlLit: Between Literature, Performance and Memory performance art series.

Founded by Kimberly Juanita Brown, author of The Repeating Body: Slavery’s Visual Resonance in the Contemporary (its cover features the iconic work of artist Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons, “When I Am Not Here/Estoy Alla”), The Dark Room is an interdisciplinary group of women scholars and artists who meet during the academic year to closely read current texts on a wide variety of themes including critical race theory, cultural criticism, media studies and visual art.

Most recently The Dark Room gathered at Mount Holyoke College for Fifth Exposure, our yearly symposium, which featured keynote remarks by Jacqueline Goldsby, chair of the Department of African American Studies at Yale.[2] Goldsby’s lecture “The Art of Being Difficult: The Turn to Abstraction in African American Poetry and Painting During the 1940s and 1950s” argues for the reconsideration of postwar abstraction movements within the context of its epistemological terms: dense formalism, obstinacy, porosity and experimentation. As such, Goldsby offered nuanced modernist connections within the work of painter Norman Lewis, poet Gwendolyn Brooks, and novelists James Baldwin & Ralph Ellison.

It’s also during the “Bodies of Art” panel that I shared the stage with multimedia artist Amanda Russhell Wallace who discussed her practice of creating work that is preoccupied with identity formation, personal narrative, and history.

For my lecture, “#BlackGirlLit: Interrogating Literature, Live Art & Documentation,” I discussed the project’s curatorial premise of investigating the connections between live art and the written & oral traditions of both Americanist and diasporic black feminist/womanist themes. Along with my work, #BlackGirlLit puts the work of Ayana Evans, Kal Gezahegn, Tsedaye Makonnen, Marcelline Mandeng, Helina Metaferia and Bryana Siobhan into conversation with one another.

Helina Metaferia, "Slow Dirt," photography by Tiph Browne.

I also note the salience of Valerie Cassel Oliver’s groundbreaking exhibition “Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art.”[3] The richness of the “Radical Presence” exhibition guided a previous discussion between Evans, Metaferia, Makonnen and I during “What It Is, What It Ain’t,” an event that was curated and presented by Metaferia and Esther Neff at Panoply Performance Lab in 2015. Witnessing Metaferia’s performance of “American Tribalism,” based on text from Nigerian author Chimanda Adichie’s novel, Americanah, that evening inspired my question regarding how black performance art relates to black feminist/womanist literary traditions. The connections reach further when we consider that the phrasing, “what it is, what it ain’t,” is an intertextual allusion to Ellison’s 1952 novel Invisible Man.[4]

In further complicating the meaning of #BlackGirlLit, which riffs off the #BlackGirlMagic hashtag coined by Auntie Peebz, I find it useful to also think through how and why black performance artists have been historically erased from the canon of conceptual art. McMillan asks, “How do we know what we know about performance art, particularly in who makes it and what counts as such? Part of this rhetorical move is to again, question received histories of performance art.”[5]

Dell M. Hamilton, “Blues\Blank\Black,” photography by Tiph Browne.

Produced in 2016 at Five Myles Gallery, #BlackGirlLit also broadly asks: How do black bodies perform "woman-ness,” "girlhood," “femmeness,” or “queerness?" To what extent do black feminist/womanist written and oral traditions define, constrain, animate, inspire or liberate the work of black performance artists?[6]

Following through with my ongoing research into the work of novelist, playwright, essayist and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston, while drawing upon the impact of Cassel Oliver’s intervention, and the breadth and variety of performance practice exemplified by Evans, Gezahegn, Makonnen, Mandeng, Metaferia and Siobhan, #BlackGirLit offers a deft manipulation of the seven Ls: liveness, love, loss, language, legibility, literature, and labor.

In partnership with Fifth Exposure, live work presented via the framework of #BlackGirlLit included my performance of “Blues\Blank\Black,” a mash-up between the work of Toni Morrison and my interpretation of Latin American folkloric figures, (reviewed by Samuel Adams for BR&S). For Makonnen’s roving performance “We Was Girls Together,” she bestows participants with a crown of flowers and asks them to look into a hand-held mirror while they read passages from Morrison’s novel, Sula. Siobhan’s performance referenced Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God through process and metaphor via the use of wood, cinder blocks, clamps, fabric, charcoal and lavender.

Tsedaye Makonnen, "We Was Girls Together," photography by Tiph Browne.

Rounding out this follow-up staging of #BlackGirlLit also afforded an opportunity for attendees of Fifth Exposure to view still images by Tiph Browne that capture Gezahegn’s poem “Seasons,” which conveys the tensions of gender, blackness, and ancestry, as well as work by Evans, Mandeng, and Metaferia.

For Evans, who recently performed at the International Festival of Performance Art in Martinique, athleticism and repetition are embedded in her practice, especially so in “Stay With Me” where she completes two hours of jumping jacks in an evening gown, heels, and make-up. In “Frying Chicken,” Evans’s collaboration with David Ian Griess, she refuses negative connotations, and juxtaposes the sexualization of the black female body with the traditions of making of Southern-style fried chicken for family gatherings.

Cameroonian-born, Philadelphia-based Mandeng, creates work that is informed by the African Diaspora and those influences are articulated in the single-channel video “Marcelline: In My Own Image.” The surrealist silent video weaponizes Audre Lorde's, Uses of The Erotic: The Erotic As Power and couples its force with the 2015 Baltimore uprising, using the non-linear history of transgender/gender-variant people to situate the work.

Ayana Evans, "Stay With Me," photography by Tiph Browne.

Metaferia’s collection of documentation included clips of Home | Free, a live performance at her recent solo exhibition at the Museum of African Diaspora in San Francisco, which activated the objects in the exhibition with sound, text, and movement; Irrevocable Condition, a three-hour unfolding of writing and smearing a quote from Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room; and These Words Matter where tribute is paid again to Hurston through walking and the material and wearable resonance of obsolete library catalogue cards.

Observing that the shared themes within #BlackGirlLit were generative for a panel discussion organized by Mandeng and hosted by Joy Davis, Devin Morris, 3 Dot Zine and the Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts also anchors my belief in the project’s cogent intersectional possibilities.[7] Even with knowing that the path of the artist as citizen is inherently fraught there is still the certainty of Brown’s acute contention that “a negotiation of word and image brings the body into focus, brings history into the frame, and whether the work is literary or visual, the pattern of repetition remains the same.”[8]

- Freiman, Lisa D., Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons: Everything Is Separated by Water, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Yale University Press, 2007, page 55.

- “Fifth Exposure,” organized by Professor Kimberly Juanita Brown, Chapin Auditorium, Mount Holyoke College, May 6, 2017.

- Valerie Cassel Oliver, Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art, Contemporary Art Museum Houston/Distributed Art Publishers, 2013, page 10. The exhibition was mounted between 2013-2014 at the Museum of Contemporary Art Houston, Grey Art Gallery/New York University, & Studio Museum in Harlem.

- “‘Now black is…’ the preacher shouted.’, ‘Bloody…’, ‘I said black is…’, ‘Preach it, brother…’, ‘…an black ain’t…’” Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man, Vintage Books, 1995, page 9.

- Uri McMillan, Embodied Avatars: Genealogies of Black Feminist Art and Performance, New York University Press, 2015, page 4.

- #BlackGirlLit: Between Literature, Performance and Memory, curated by Dell M. Hamilton, Five Myles Gallery, Brooklyn, May 21, 2016.

- 3 Dot Zine presents Brown Paper & Small Press Fair for Black and PoC Artists, Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts, January 28-29, 2017.

- Kimberly Juanita Brown, The Repeating Body: Slavery’s Visual Resonance in the Contemporary, Duke University Press, 2015.