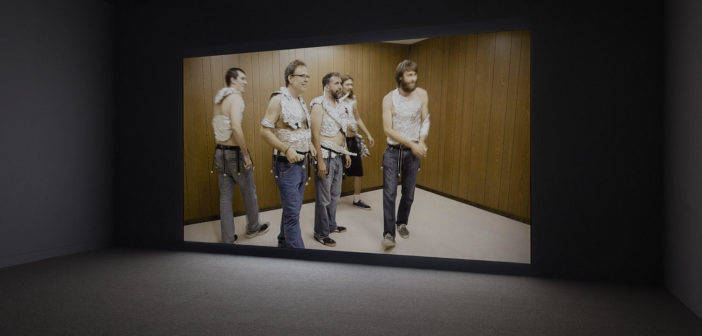

Masculinity and social isolation is a topic of current debate and much speculation. From militias to communities of Internet trolls, American men are forming social ties through aggression, violence, and misogyny. Artist Kenneth Tam’s video Breakfast in Bed (2016), recently on view at the MIT List Visual Art Center, is an offbeat counterpoint. For his video, Tam created a fictitious men’s social club composed of paid participants he recruited over the Internet, and who he loosely directed to perform a series of actions that exist somewhere between team-building exercises, improv, and games. Tam edited hours and hours of footage down to a half-hour of short vignettes that range from funny and touching to mysterious and discomforting. I talked with him about his social experiment that tests the boundaries of male bonding.

Joshua Fischer: What first sparked your interest in men’s groups or social clubs? Before this video, you had been filming your one-on-one encounters with people recruited over websites like Craigslist. Why a group?

Kenneth Tam: A group seemed more like the natural next step in terms of what I was interested in doing, at least in the sort of social dynamics that I was interested in producing.

I had seen some random images, on the Internet of course, of a random group of adult men that were in a room. I still have these images. They were really strange and bizarre because you had no idea what the context for this meeting was. They were just sort of there in this room. They seemed to be celebrating some kind of meal. They didn’t actually look happy. They didn’t look like they were celebrating, but they were gathered around the table eating some sort of meal. I couldn’t tell if the photos were staged or not, if there was some artistic intent behind it. I couldn’t tell if they were documentary and that this was actually some sort of social club that existed that these men were actually a part of. There was something really compelling about seeing a group of men together, not exactly happy, but at the same time, it seemed like they needed to be there with one another.

That got me thinking about these other existing social clubs that for men satisfy a certain kind of emotional need. This whole phenomenon of men-only clubs or groups that are ostensibly about some other activity – cigar clubs or church fellowships – but I always thought that it was a way of getting to a space of affection or intimacy. It had to be constructed as a way to get men to hang out with one another or the idea that there's an activity that has to mediate male social activity. All of that led me to want to start my own club of sorts and thinking about what that would mean, what that would look like, especially in terms of what I was already doing as an artist.

JF: As you studied these actual groups like cigar clubs, did you ever visit those groups? How far did you take it?

KT: I mostly did research on Youtube. There's a lot of documentation of these clubs made by the members for other members, I assume mostly for internal consumption or recruiting. I saw a lot of videos of these weekend getaways with religious groups.I can't remember if any were secular. They were all promoting this event like the big weekend is coming up, guys. It's happening. There's a lot of anticipation. This is something the guys look forward to: a big group of men in the forest or the woods, playing games, having a good time, but more specifically getting away from their families, or whoever it was in their lives, and feeling the need to be together in an all-male environment and doing whatever it was that they needed to do. I was looking at a lot of that kind of material.

There's this great film called Routine Pleasures. A french filmmaker who lives in San Diego, Jean Pierre-Gorin made this really beautiful film about this model railroading club. [The characters’] day jobs are in the aerospace industry. They were engineers during the day, but at night they set up this elaborate model railroading club that they participated in. It's very sweet. It's kind of sad, but at the same time, it's very endearing to see. There's a lot of performance involved. These guys pretend to be train conductors. They adopt this other persona and once or twice they get together and play. Adult men playing, I thought that was really informative.

JF: You made the decision to not find one of these groups to work with, but you constructed your own. Can you talk about creating this artificial group?

KT: I definitely thought about working with an existing one, but I felt that for my purposes it wouldn’t work. I wanted to treat this group almost like a sculpture and build it in that way to be able to play with it and manipulate it in a way that an actual group would not allow me to do. More importantly, the fact that an already existing group would have too much investment in one another, and for me to come in there, it would probably be very disruptive and potentially even damaging to the relationships within that group.

I wanted whoever I would work with to feel like they could perform in some other way. I wanted this thing I was creating to be wholly apart from their lives. I thought it was important that it be entirely artificial, even a fantasy at some level.

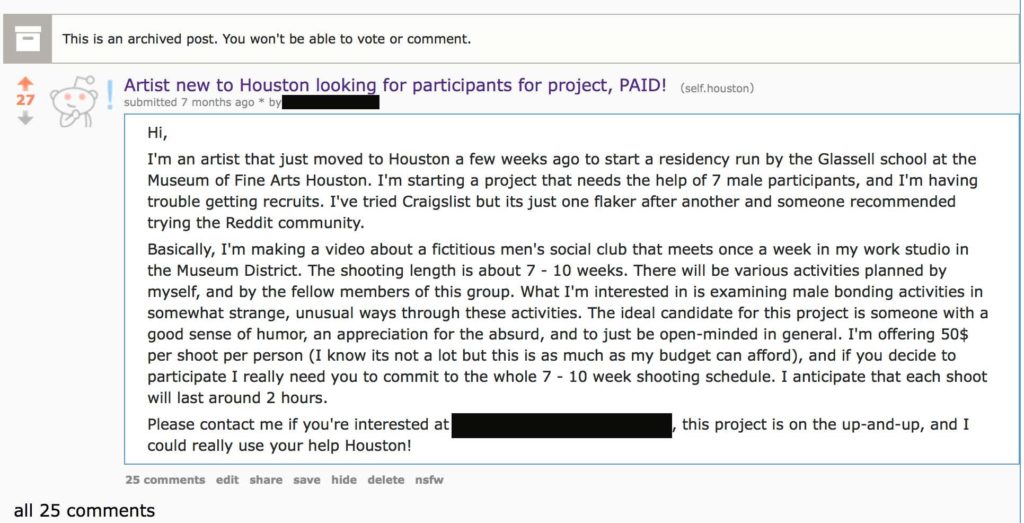

So the way I went about recruiting them was to go online and place ads on places like Craigslist and Reddit and just see what the responses were and what kind of people would be interested. I was looking for about seven guys to work with, and I had ultimately eleven people that said they would agree to do it, which was more than I expected. I picked seven of the guys that seemed most interesting and seemed most willing to put themselves out there for the sake of the project.

Screenshot courtesy of the artist.

JF: Andy Campbell in his essay for the MIT brochure talks a lot about the significance of the room you built inside of your studio and filmed in. Did you begin thinking about the setting as you developed the solicitation? When did this setting refine itself?

KT: [The setting] was always integral to the project, and in a way, it is another character. I knew I wanted to shoot in this space that referred to a rec room or basement, an ersatz domestic setting that I think certainly Americans are familiar with. At the same time, I was always interested in how these groups needed to do their male bonding in hiding, like basements or secluded spaces. They always had to be in a space removed from the public eye, slightly hidden. I knew I wanted to recreate that. I wanted a space for them to feel apart from reality, this fantasy element where they can adopt a new persona or enter into a performance. Come in here and then something else happens.

Kenneth Tam, Breakfast in Bed (still), 2016. Courtesy the artist.

JF: How did you then develop which games you wanted them to play?

KT: A lot of what I ended up having them do was not spontaneous, but it was designed or developed week to week. We met once a week, typically on a Monday or Tuesday night for seven weeks. We took a break -- I think it was Thanksgiving or the holidays -- and I felt I needed to stop the project to see what I had. We continued for two more weeks after that. Most of the footage is from the original seven weeks. I wanted to mimic the structure of an actual club on a set date that was reoccurring.

As for the games, I did a lot of Youtube research on party games, corporate team building exercises, theater improv games, so the things that you see are a mix or partially inspired by all these different activities. These activities are meant to either build trust or to facilitate some kind of intimacy or about creating a space where people are allowed to feel vulnerable or act differently than the way that they do as their day-to-day selves.

Some of the games are things that already exist. Some are things that I changed slightly or made slightly more absurd. The activity with the bells was actually a reference to this amazing Cameron Jamie video where he made this video [Kranky Klaus] about Krampus, which is the Scandinavian take on Christmas where men wear costumes with bells attached to them. I sort of adopted that for my own purposes.

I was very much interested in this idea of ritual... Rituals are constructed activities that the participants invest with a certain type of meaning, either symbolic, emotional, or psychological. I thought that the bells could feel ritual-like even though [they are]completely absurd in the way that I use them, as well the use of masks too -- the idea of performance and having this other persona but again acting in an absurd away.

The scene where [the participants]just talk to each other came about from another activity which originally I called “sincere whispering.” The idea was that each guy would whisper something complimentary to another guy. That didn't work out very well. It was really uncomfortable for them and for me to watch, so we had to scale it back. Ultimately it became a thing that was in the video. Some of these activities we redid. They weren't rehearsed, but they were modified and done more than once over the course of the week, getting it to a point where I thought it was interesting. There was definitely some directing involved on my part, but also workshopping or experimenting.

http://https://vimeo.com/201503036

JF: A great moment in the video is the game of dabbing the paint on each other. They're caught up in the fun of it, like a jovial mixture of paintball and action painting. Can you talk about that scene and how much you think about the image you're creating?

KT: That activity was really rushed. It was the last thing we did in week seven before we were all going to go on a long break. I think it was structured as a game with a prize. In my mind, I thought it was going to happen in a very civilized manner. Everyone was going to be running around dabbing each other very modestly. I had no idea that they were going to be so caught up in it. In terms of the image I wanted to create, I do love all these references to action painting or paintball. I'm not exactly sure that was what I expected to happen. I didn't think it would become such a frenzy. I think that what I was most interested in was this touching, using the game as a way to allow that to happen, but in a less self-conscious or stigmatized way.

JF: One thing with team building is that part of camaraderie when we are doing these activities is that we know we are going to have to take part too. With your video, we are outside of it as viewers, and we don't have to engage. We don't have to be embarrassed and some parts of your video are very funny. Are we laughing with them or at them? I wonder how you see the viewer.

KT: I would hope that the question doesn't become solely pivoting between “are we laughing at them or are we laughing with them,” i.e., are we strictly outside or inside of this group. The viewer is implicated in some way. When you see these guys performing, you ultimately question your own performance or your own assumptions about what these guys can do.

If you find yourself laughing at them, I would love for you to interrogate yourself. Why am I laughing at them? What about this behavior is not only funny but why can't these guys do this? Why do I feel like I have to laugh at them? How do we allow the normative to judge these men? How do our understandings of what men can do with their bodies in a group allow us to judge their activity? The whole project is built on this idea of questioning these expectations we have.

I think this goes to all my videos that the audience is implicated through its watching, but obviously, you're outside of it. You're seeing a representation of an event that has already transpired, but at the same time, there is a kind of investment. Why is this happening? Why is this being allowed to happen? This feels wrong. Why do I come to that conclusion or why do I make that assumption? There's a constant engagement of the audience that whoever is watching to ask these questions.

People often ask me about the humor. Why is this so funny? Why the absurdity? I think that is a way to enter into a space of critique. Humor can open up a space. Humor can create an alternative way of thinking about the world. I use humor as a vehicle for some sort of social critique. Opening up a space where one can reimagine how the relations between men can be.

http://https://youtu.be/Y15AiEeKxg0

JF: In your conversation with Bruce Hainley at The Hammer, you show clips from the reality show Impractical Jokers, and Bruce Hainley mentions in his essay the show jackass. Those shows are built around humor, but not about vulnerability, more about humiliation.Could you talk about how your use of humor separates itself from those shows?

KT: I wouldn't put my work in a sort of positive space and those other two shows in a negative one. They're both instructive in their own way. When I did the talk with Bruce, I didn't necessarily show Impractical Jokers to criticize. I think there's something useful to see within that too in the way that humor used quite differently also creates a kind of space for these men to be intimate. Especially in jackass the way the men touch each other in their erogenous zones, their ass, and their dick. These spaces that are normally off limits to straight men, but yet within the space of the show it's always the target.

The humor and the crazy stunts allow for these guys to touch other. I don't know if they’re conscious or unconscious ways of getting at these repressed impulses. In that sense, I think jackass can be thought of as a constructive exercise between these kinds of macho guys, but at the same time allowing for these other things to happen which I think is interesting especially since we're allowing it to be broadcast and disseminated as entertainment. I think something more profound is happening.

It’s important to note that these guys are friends and that kind of activity already happens with all male groups. This is actually how men typically get along. I was reading an essay about how men bond, and it’s not through positive speaking. It's not through sharing of emotions, but it's through competition, through making fun of another, sort of gentle ribbing. That is the normal way for men to express affection with one another at least from a North American context. Obviously exaggerated, it's made hyperbolic for the sake of entertainment, but there is some truth with what's happening there. It is a normal mode for interacting among men.

JF: I was wondering how [these forms of entertainment]are different from what you do, but it is interesting how you're pointing out what you're learning for these shows and then adapting it in your own way.

KT: Maybe it's not that differently actually. That's the point to compare--not so much contrast-- how my video and Impractical Jokers exist on some kind of spectrum of permissible activity. Even though these guys are using humor to shame, to embarrass, to humiliate, there is some truth that those activities are a way of displaying affection ultimately. The activities I construct try to do similar things without the stigma.

Kenneth Tam: Breakfast in Bed ran through May 21 at the MIT List Visual Arts Center.