Vitreous Bodies: Assembled Visions in Glass centers on the material of glass, but maneuvers past the typical, disposable aftertaste of many material-based exhibits. Located at MassArt’s Stephen D. Paine Gallery, the show gathers over a dozen international artists who use glass either primarily or sporadically. In fact, the longer I lingered in the gallery and observed the variations–from scale to viewer participation to the sheer logistics of how the pieces were installed–the more I felt that glass might be the only link between these artists. Overall this variety leads to an enjoyable show of dichotomies.

Daniel Clayman. North 41.47° West 71.70° Silver, 2017 and North 41.47° West 71.70° Gold, 2015. Glass, gold, and white gold leaf. Courtesy of the artist and Habatat Gallery, Royal Oak, MI. Photo by Eduardo L. Rivera. Timothy Horn. Silver Convention, 2015. Nickel-plated bronze, lead crystal, and silver foil. Courtesy PPOW, NY.

One of Daniel Clayman’s amorphous sculptures, for example, greets visitors near the entrance of the gallery. Its nebulous shape, framed by its modular, almost reptilian surface, looks like a large nugget of some precious metal while also appearing very much assembled. Despite the appearance of construction, it still doesn’t look like any one thing. Directly behind it is Michael Joo’s Dissembled: a pile of large, warped sheets of glass with ceramic “appendages” that resemble handles. Clearly, these are police riot shields, apparently discarded in the middle of the gallery. Unlike Clayman’s glass blobs, Joo’s artwork purposefully does not have the luxury of vague connotations. When these normally staunch objects appear stacked haphazardly and casually on the ground, suddenly the gallery appears not only a space to look at art, but also a space where potentially aggressive events took place. Also, between these two works, the physical properties and connotations of glass are not as firm as usually thought. With the visibility of riots towards police violence in recent years and large protests of Trump’s election even more recently, Dissembled is an unnervingly timely piece.

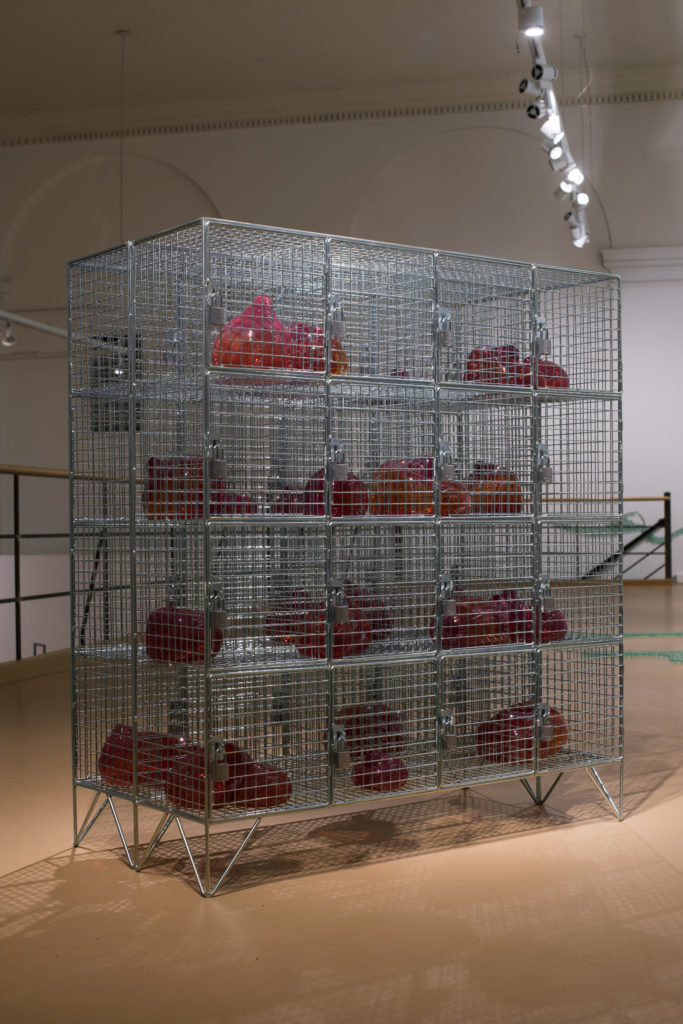

Mona Hatoum. Cells, 2014. Zinc-plated steel, glass. Courtesy of the artist and Alexander and Bonin, NY. Photo: Eduardo L. Rivera.

Remarkably, visibility is surprisingly difficult to come by in this show about glass. Kanik Chung’s freestanding sculpture The Presidents succinctly illustrates how glass is not a medium that’s always the easiest to look through. The piece consists of forty-four panes of glass stacked vertically back-to-back, each with an ink drawing of a U.S. president (ending with Barack Obama). When pressed so close together, though, each drawing becomes drowned out in the blur of the crowd. It’s impossible to extract the individual from the overall history to which they contributed. Looking through glass, like looking back at history itself, can be both clarifying and obstructive. As interesting as this sculpture is, it has the least to do with glass of all the works in the show; there are plenty of transparent materials that could’ve accomplished the effect Chung reached. Petah Coyne’s sculptures, on the other hand, very much deal with glass: its history as a decorative object, its physical mutability, and its enchanting visual properties. Coyne’s three sculptures are made within a specific template: all are flowers, all are protected in a vitrine with ornate ribbons of some kind, and all are portraits of influential women, like Catherine the Great and the Empress Dowager Cixi. Each acquires its look through the different colors of ribbons and flowers. The articulation of the petals, which often look more like limbs, gives the flowers their specific charm and makes them feel a lot more sinister than casually decorative. Coyne’s sculptures operate in a fascinating nexus of what we proudly put on display and what we quietly conceal. Mona Hatoum’s Cell on the gallery’s upper level elicits a similar concoction of menacing and sympathetic responses.

Maya Lin. The Flow of the Charles, 2017. Glass marbles, adhesive. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Eduardo L. Rivera.

Then there are works that disrupt the entire gallery space. Obviously, Maya Lin’s The Flow of the Charles is the headliner of this show. It’s hard not to be when you make a piece that consists of over 25,000 glass marbles that disseminate all across the gallery’s back wall like a sentient blob. Lin’s work often deals with the environment, and The Flow of the Charles is no exception. If the name didn’t give it away, it’s based on a satellite image of the Charles River, intended to give viewers a digestible image of the living organism of the natural environment that surrounds them. As serious as environmentalism is, the theatricality of The Flow of the Charles is also pure entertainment. It’s just fun to watch the horde of marbles slip into vents and curl over railings, conquering as much space as it can. Arlene Shechet’s Out of the Blue uses a similar strategy of gallery intervention, but it’s much quieter and strict. A glass cast of rope is severed into pieces of differing lengths then stretched across a gallery wall, giving the illusion that the rope is going through the wall like a stitch. The color is gorgeous, and there’s a calm sense of satisfaction when following the steady pacing of the individual casts. Even if a little too measured, Out of the Blue is a great example of how the strength of glass might be because of the porous possibilities of its use. Unlike most material-based shows, Vitreous Bodies does a great job of presenting a scholarly and entertaining exhibition without turning its subject, glass, into a caricature of itself.

1 Comment

Call me a stuffed shirt, but I like to know who, what, where, when….

Name the place where I can see the work discussed, and dates. please.