Back in the olden days, groups of people united into tribes and began to hang out and draw deer and suns and little stick people on cave walls all over the world. Seems like not much has changed.

This is the angle juror Denise Markinosh took on the Mills Gallery’s 19th Drawing Show. Each piece then becomes a sort of relic of this moment in culture. Looking around the room with that in mind is not particularly reassuring: whether compositionally or through their content, these pieces distress and disturb.

Immediately on the right, Nathan Lewis’ towers loom uncomfortably…somewhere. It’s not clear if it’s even overhead. They give no sense of place or perspective to the viewer and end abruptly, leaving one stranded in an expanse of white wall. They oppress and menace. Equally disorienting is Nicholas Santore & Valerie Ferus’ three-point perspective drawing. Its depiction of geometric space pushes and pulls with flatness and dimension. At one point there is a sensation of space, or division of it, and then there is suddenly only a flat wall. Tory Fair’s floor drawing is spatially clear, but the lines’ intentions (to lead or divide) are not. They are reminiscent of the lines used to delineate courts or sports fields and give the overall sense of something wholesome distorted.

Two pieces by Anna Hammond and Amy Jean Porter depict a hero’s journey in Cartoonland. On the left, little worms fly around and lightning flashes over mountains. On the right there’s movement from the city. Paper airplanes fly out past palm trees and coconuts, maybe to some promised land where no dogs are allowed. They offer the viewer plenty of characters, but nothing to follow through whatever story they’ve created. Similarly overwhelming, but to a much greater degree, is Nick Z and Mister Never’s roomful of graffiti. It’s packed with clouds and characters and ambiguous maxims (It’s been a long time coming; Trap or Die 1977) in pink and blue Hello Kitty (minus the cutesy quality). The eyes move around it like a board game: systematically but not freely. It’s frenetic and depicts a tremendous amount of confusion, but has a graphic backbone that makes it the most reassuring piece in the show.

Several works use their beautiful qualities to mask or obscure something much darker. Amy Ross’s Garden depicts mushrooms with chicken feet and flowers with bird heads, with sheep heads dangling overhead from the tree branch in tasteful, muted tones like creepy illustrations from a Russian fairy tale. Jessica Doyle's landscape shows clean divisions between nature (color, broad, open mark making) and humans (black and white, delicate, controlled line) and could well be a depiction of the Underworld. Her characters recur but not as in a narrative so much as in a family album. They stare ahead with dead eyes. Katherine Desjardins draws a little boy Dick and Jane style. Happy toys crowd the right end of the bed where he’s playing, but to the left the bed stretches out with a world buried in its wrinkled blanket: a house, a tank, an explosion, eyes spying with binoculars. Layers hiding under in grey are unreadable. Kristin Rae Simonsen’s little girls who seem like porcelain dolls that haven’t been well taken care off. They’re messy and unclean, and what ought to feel pure and innocent feels ghostly.

In Rebecca Doughty's Holes larger, straight-faced rabbits hold smaller ones by ears or ankles over the openings. The dour little figures disappear into the wall with light mark making or erasing, or stare back unabashed. Magda Fernandez builds an image out of noise that appears bright, until you step back to see a dog staring at you from the arms of a big, scary bunny. Headphones at the wall play Johnny Cash singing about his “dirty, old, egg-sucking dog.” Thinking about the term egg-sucking and looking at the piece is nauseating. Someone looking back from the distant future may well wonder: how were bunnies so dark?

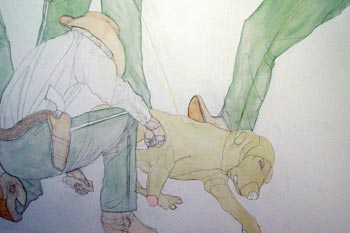

Other pieces go for a more direct approach. To the Victors Go the Spoils depicts a lapse of time in which a sheriff type pulls out his penis and pisses on a dog, then cuts it up and takes the pieces. The image is so violent (due to the cock as much as anything else) that it’s hard to look at. Neil Bender offers us what could be mistaken for a portrait of a large intestine. It is a sickening growth – a mess of body parts – all lurid pink. White oozes, cuts through and in at the edges where pieces are cut off – or, more accurately, cauterized. And watching Necee Regis’ tiny, graphite planes duck in and out of the columns between the front windows, it’s hard to miss the 9/11-ish reference.

The fact that these drawings are right on the wall gives them more weight, despite their impermanence. They have a physicality that a sheet of paper will never have, and the connection with the pre-historic practice of art making lends its own gravity. Not all the drawings deserve a more grave reading and so in some ways the Drawing Show is trapped between a superficial survey of the moment and something much deeper. Posterity will decide.

Links:

Mills Gallery

"The 19th Drawing Show" is on view November 18, 2005 – January 8, 2006 at The Boston Center for the Arts Mills Gallery.

All images are courtesy of the artist and the Mills Gallery.