Leah Piepgras was finishing final preparations for her solo show, Parallel Universe, now on view at GRIN when we had the following conversation. It was early October and we were eager to talk about all things abstraction, Richard Serra, physicality, opposites, materiality, Mierle Laderman Ukeles, time, labor, and synchronism. We hadn’t met yet but spoke over google doc, which allowed our conversation unfold in real time as we juggled our everyday lives.

Reading our conversation now, I’m struck by the hope that Piepgras intones when she says she says that for her, “abstraction is a way to seek answers.” Piepgras has tenaciously created performances, paintings, drawings, and objects for decades. On view through November 19, Parallel Universe explores how the natural, human, and spiritual exist in tandem, as well as our need to “navigate” what is unintelligible.

Leah Triplett Harrington: You’ve said that you have you have a “tendency to work on everything at once, so each piece is part of something bigger.” I think that dovetails well with what I know about Parallel Universe so far, and what you articulate in your statement, that in your work you “ask questions that do not have answers but, by being asked, posit truths and answer in feelings and intuitions.” Will you describe how this synchronicity and clairvoyance activates or relates to your work?

Leah Piepgras: My ideas are in a state of entropy in my mind and by physically making work I am able to come to an understanding that is not a verbal, but instead a visual language. By working on multiple pieces at once I am able to approach the same idea from many different vantage points. I allow myself the time and space to see what happens. These pieces are also labor intensive, so the process has time to think built-in which, in turn, allows for the thinking about ideas while making the actual work. Different pieces have different orbits but they all circle back to the same center.

A good example of this is Holding Space, a 39’ prayer necklace with 108 beads made by casting the space between my hands with plaster. This is an idea of time becoming tangible and the body as a place within space that had several iterations before I found the one that answered all the questions I was asking in a way that “feels right.”

Holding Space started from two different points (images, ideas, visions): one, a long looped rope that has no beginning or end with the idea of physically pulling yourself through space and time and the sheer labor of existence.

Leah Piepgras, Holding Space(Prayer Necklace) Cotton rope, plaster 39 ft, 2016.

Second, thinking of the body as a place instead of a thing and trying to find space within our physical being, I took casts of the space between my thumb and middle finger while they were touching and made tiny plaster masses that looked like landforms. I think a lot about the Coastline Paradox and how a known space can really be undefinable. Through the process of making those things the ideas merged and formed something new that I would not have thought of or imagined before.

Each plaster bead on the rope takes about 10 minutes. I take mixed plaster in my hands when it is still runny, but thick. The plaster is cold and formless so I have to squeeze my hands together tightly to hold on to it. I then close my eyes and hold the plaster and meditate, pray for rightness in our world, and think about things that are of great concern to me that I have no control over; things that are happening in our world that seem so removed from the privilege of getting to make art (anger, hatred, global warming, poverty, violence, and yes, our insane election). I think about people that I care about and hold them in my mind. While I am sitting there, the plaster in my hands transforms from a liquid to a solid. It becomes warm and as I peel my hands away, a space which did not exist before becomes a reality. Something from nothing.

LTH: There is a lot to talk about here! Firstly, I want to touch on the 108 figure. Richard Serra’s Verb List has 108 ‘terms’ of verbs. Serra uses those transitive terms to create something from nothing using his preferred material (at least in the late 1960s) of molten lead which, when ‘acted’ upon, assumed whatever shape that Serra gave it.

Leah Piepras, Holding Space(Prayer Necklace) Cotton rope, plaster 39 ft, 2016.

Secondly, beads as a form is really interesting as beads are smaller, particular parts strung together to complete a larger whole, which parallels your interest in everything all at once. Beads can be many things--sweat, decorations, jewelry, prayers. How did you arrive at the bead form? Do you see it as a form or a material? Do you perceive a difference?

And thirdly labor. I’m also struck by essential and performative nature of “the sheer labor of existence.”

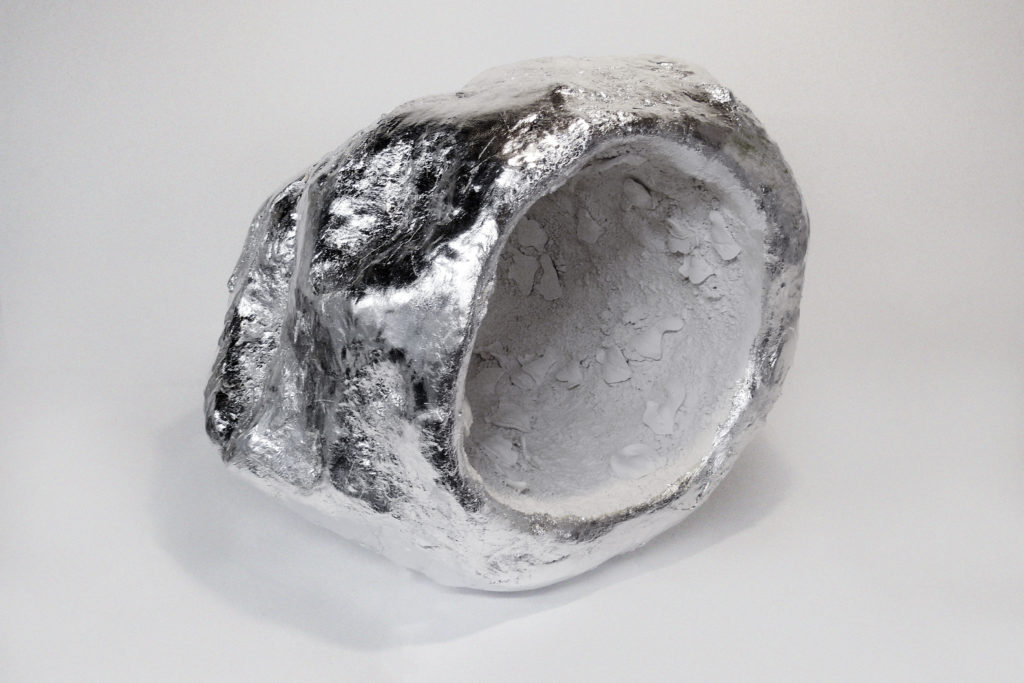

Leah Piepgras, New Geology, Mirror, plaster, Sumi ink, foam, wood, Variable Dimensions, 2016.

LP: I love that Richard Serra’s verbs become a map to physical action and the objects made are manifestations of time+actions. At the same time, those actions are an experiment with materials and by doing the labor you end up with an object. I think of those experiments in terms of science. I love the way that science and art really start from a very similar place- observation, and recording results; specifically really looking in order to see something you haven’t seen before or to find a truth. I am so curious why Serra used 108 words? I used 108 beads very specifically to link to the form of the mala, a prayer necklace used for saying mantras in Buddhism. I really wanted that connection of meditation being rendered in physical act.

LTH: I’m thinking a lot lately about how action relates to material. And by action and material, I am thinking both inside and out of aesthetic terms. How does material dictate action? How do we experience action in the materiality of the work? How do modernist tendencies-- abstraction, conceptualism, minimalism-- affect material? And vice versa?

LP: I switch materials and processes a lot based solely on the idea that I am thinking about. I have a mental list of materials and actions placed upon those materials from past experiments, so I can kind of visualize and map out what my process will be. Of course, this almost never goes as planned, which is when most of the good stuff happens.

One thing that I play with a lot, usually in the same piece, is letting materials be in their “natural” state vs. fully manipulated and used to construct recognizable imagery. For example, in Sleep (200,000 years) the hydrocal is used in several different ways. The eyes are cast, versus the hydrocal which is just barely wetted by mist and left in an untouched state (by my hand). Of course, I am manipulating it but it’s physical attribute of beading and crusting up happens as a property of the material just by being exposed to mist more easily than me making a mold. I guess it is more a distinction of less touching and less visibility of the actual “artist's hand”. I think in this show, I try to allow these particular materials to be flexible.

In Holding Space, I really wanted the necklace to be a big space that your whole body could be engulfed by it. I loved this idea of making the beads and compressing my thoughts and physical energy into a small action to gain power by being part of something larger than itself. The necklace as a form is like a big mouth with jagged teeth, something fierce that could swallow you whole and at the same time protect you.

I have taken this approach of small parts making a bigger object in some way in all the pieces in the show. Working with tens of thousands of mirrors, I have thought a lot about how small parts dictate form and have rules of their own about how they can be put together in an organic way. I have used hundreds of cast ears and sleeping eyes to make objects that are singular but bigger than any one person. Using multiple incarnations of body parts has also been a way to show a passage of time and repetition of actions.

LTH: In looking and thinking about your work, I’m struck by the parallels (!) in your descriptions of the work and in discourse around early abstraction. Mondrian, Malevich, and others --they used abstraction for utopic ends-- they were seekers, looking for a purity or truth. So it’s powerful to consider work like Listening to the Sky through that utopic lens. This work totally resists hard-edged or systematic abstraction, however. It’s a biomorphic, almost humanoid shape, with energetic loose dripping and repetition of the ambiguous ears. The abstract texture here is very emotive, completely suffusing the work with a sort of primordial feeling. It’s very sensual, very human; it’s almost like there’s a person hiding beneath the shape, giving contour, striving to hear with whole being what’s going on outside. Similarly, your beads are given shape by a body on the outside.

Leah Piepgras, istening to the Sky (Stupa) Plaster, hydrocal, wood 59 x 35 x 28, 2016.

LP: I guess this is a utopian way to think about art, or making art, but for me making art is a spiritual pursuit, a visual philosophy, a visual poetry, and a method to live by.

Abstraction is definitely a way to seek answers for me. Synthesis of specific imagery or information is a way to make the personal universal and a route to the purest understanding of an idea/form/shape. It is a way to get down to the core. In Listening to the Sky (Stupa) I really wanted that feeling of the weight of many bodies, heaped; like a long time had passed and layer upon layer of being had come to this place to listen and understand.

I have also been looking at stupas as a form, and was thrilled to learn that stupa is the Sanskrit word for heap. This realization was too good to be true because the Heap Paradox is one of my most favorite paradoxes. The Heap Paradox essentially questions states of being.

LTH: In the statement for this show, you describe breathing (inhale, exhale), as “an endless loop of opposites.” I can see this in the beads, and I feel it in the mirrors...mirrors twinkling like the stars in the sky that we can never completely, fully see. We can only experience it as it turns. And you have a work in the show comprised of small mirrors spinning on a cylinder, Parallel Universe/Prayer Wheel?

LP: The idea behind Parallel Universe/Prayer Wheel is that it functions like a traditional prayer wheel where by spinning there is a repetition of prayer for each rotation. In this case, I have made those prayers visual with reflected light which does look like the universe spinning out away from you; a visualization of your thoughts being flung far and wide into a dizzying space.

This leads back to our discussion of abstraction. I was not thinking of this as an illustration of the universe, but a private parallel universe for the person spinning it. In this model, the “stars” are not in a specific order based upon our actual understanding of cosmology, but on an order dictated by the placement of the mirrors. I really thought of them as organic components and used them under a set of rules that they themselves imposed. This physical pattern-making creates a repeated pattern carried out through space like an echo.

LTH: I noticed on your resume Daily Life Performances including but not limited to (1998 - present), along with the list of life events and actions poetically titled. This reminds me of Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ MANIFESTO FOR MAINTENANCE ART 1969!, which is getting so much very well-deserved attention right now. But while Daily Life Performances including but not limited to seems related to Ukeles, you are using an abstract idiom. Your work is so poignant, very nuanced in its simplicity, in its expressionism, while MANIFESTO is much more loaded in its syntax.

LP: I love Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ MANIFESTO FOR MAINTENANCE ART 1969! I think definitely my Daily Life Performances came out of that vein of feminist performance and art-making. I also think that this type of work and the labor question come out of a necessity to live a righteous creative life while also being a wife and mother (or really just a conscientious person who cares about other people)! I live in a family and, yes, there is a lot of labor- but it has been a huge source for time to think and reflect about what it means to be human and conscious in the way we live and also to comment on it. Pearl Necklace, Consummation Sheets, Consumption Dinnerware are all directly linked to the labor of living of my daily life. More subtle and very rich is the benefit of peeling potatoes, which starts with a rough and dirty organic form, and using that form to dictate a smoother, refined and crystalline shape that comes from within.

When I talk about the labor of existence I mean that in a couple of ways. First, I think in our world (this particular parallel universe of people who would be reading this) everyone is always busy. There is the list of “have to” and the trick is to turn that around and find the joy in living. Second, I also mean it in a primordial way. We all have physical drives that propel us forward and I think making art for me is an innate desire that can’t be overwritten. In order to be fulfilled, I crave labor and the action of making things in exchange for seeing something new and beautiful; actionable creativity.

Parallel Universe by Leah Piepgras at GRIN, October 22 - November 19, 2016.

LTH: Like Serra’s List, your performances are both verbs and nouns --abstraction-- which Alfred Barr famously defined as “both a verb and a noun,” meaning that it’s both an action and a thing.

I don’t want to completely compare, or get too theoretical, but all this is to say is that you allow your viewers to imagine or conceptualize these events or actions; those ideations are then in parallel with your actual lived experience or actions.

LP: I do think about how people will come to the work and hope that they will relate to it on a personal level. For me having an active physical experience, even if it is just forcing myself to really look at something, allows me to more fully understand. I often think that I make work that is a remnant of an experience, something to hold onto, a reminder or even a way back into the the action that the work is about to begin with. Naming work with descriptions of actions, or the function of the piece, is a way to invite the viewer to understand how something was made, it’s purpose, and, like a short set of instructions, gives directions to the parallel universe that I am living in.

Leah Piepgras, Parallel Universe (Prayer Wheel), Steel, plaster, mirrors, light, 51 x 23 x 15, 2016.