In the months leading up to Tory Fair’s latest show, Paperweight at VERY gallery, VERY director John Guthrie and I made two studio visits to view the work in progress. On the first occasion, I met John outside a large wooden building, an erstwhile printing press, and we tramped up the stairs to Fair’s studio to find her rearranging two sculptures. She had cast a tree in a mixture of rubber, plaster, clay, wax, and foam and they stood erect in the middle of the studio. On our next visit, the trees were lying on the ground, a cast of a tree stump had been added, and we all agreed that the campfire motif provided a strong sense of place and a conceptual anchor for the show.

Fair, a Boston-based artist and Associate Professor of Sculpture at Brandeis University, is very much a student of her own work. She allows her process to inform decisions and builds up materials only to later strip them away. In her more recent work, Fair uses personal keepsakes from her life to access memory and conjure up folk nostalgia. In 2015, Fair constructed an installation called Heap at Proof Gallery in Boston which consisted of an ashen mound of stacked objects. The pile contained casts of items taken from Fair’s everyday life and her past— a soccer ball, a mug, her grandmother’s camera, her son’s breakfast waffle. For Paperweight, Fair recycled some of these objects and infused them with her new pieces.

I met Fair at a local pub to discuss the evolution of her art and her personal growth as an artist. We talked about her formative years in the nineties working in the Arizona desert at the Roden Crater Project, a mammoth undertaking led by conceptual artist James Turrell that’s still in progress today. She also explained something called a “pseudomorph”.

Stace Brandt: Before we talk about Tory, the artist, what is it like for you to be a professor of sculpture?

Tory Fair: I love being a teacher and being in an academic context because I feel like I’m around these younger minds that are challenging status quo and language. I learn so much from being in that collaborative environment. I don’t have a big agenda when I’m teaching. I want to inspire self-reliance and for my students to make something that they want to make in their own particular personal voice.

SB: I just recently graduated from an undergraduate art program. What was your experience coming into your own as a young artist after undergrad?

TF: I think when I graduated I didn’t even know I was an artist. I thought I was going to become an architect or a restoration carpenter because I grew up in an old 17th-century farmhouse. But I did graduate with this hunch to chase after. During the summer of my junior year of college I drove out to find the Roden Crater Project that I had read about in a pamphlet—this is before the internet. I got really lucky and I ended up meeting James Turrell. The project was this confluence of all these things I loved in terms of architecture and art but also a rooting in perception and our scale in the landscape.

SB: What was it like working on a project of that magnitude? What was your role?

TF: My time at the Roden Crater was less about studio work and more about larger issues of the landscape surrounding the crater. The land out there is checker boarded with sections owned by the Bureau of Land Management, the Wupatki National Monument, the Hopi Reservation, private land parcels, and ranchers all superimposed with this huge art project in the middle of it all. I was helping with grazing rights which brought me really close to my mom’s fight to save the watershed as the mayor of our town in New Jersey. I felt like I was tapping into a way of approaching what it is to be an artist while also being aware of the politics and ecologies at play in the greater landscape.

SB: I notice that to this day your work contains geological references. How do you think your time at the Roden Crater impacted you and your art?

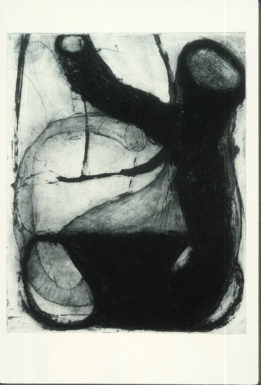

TF: I’m a total New Englander and as a young artist being out in Arizona I was completely out of my element. I grew up in the Great Swamp with stone walls and lush green ponds. Being around the exposed geological layers of the Grand Canyon, Arizona, and the whole Four Corners area was totally influential. I had done a lot of printmaking in college and in Flagstaff, [Arizona] there was a little press that I worked in. I think that whole idea of surface and foul-bite and the language of printmaking is completely analogous to the language of geology. I was printmaking a lot then and making a lot more images than sculptures.

SB: Is there any connection for you between the printmaking process and the way you make sculptures?

Tory Fair, "Untitled," 1996. Etching, 6X9." Photo courtesy the artist.

TF: I do find a productive resonance between printmaking and mold making. There is a similar compression of surface in pulling back a rubber mold that there is when you peel the paper back from a plate that’s been rolled through the press. One thing that’s been in my work for a long time is evident mold lines. Mold making for me isn’t a tool for perfection and repetition. Neither my prints nor my sculptures look the same just because the plate or the mold is the same. I’m always trying to experiment with how a marked surface or mold can produce different feelings or results. I’ve always loved that surprise. I’m sure that would drive someone else crazy, the out of control nature of it. But in some ways, it’s really in control because my materials are my ingredients and I’m just letting my ingredients inform each other.

SB: Did you have a breakthrough when sculpture became the medium which made the most sense to you as an artist?

TF: I think I was first touched by the work of a lot of those seventies artists like Mary Miss and Turrell who were thinking about the landscape—either bringing us into the landscape or bringing a sense of the landscape and scale into the gallery. I definitely had a moment my junior year when I made this very linear steel sculpture. It was about a sense of place and I took it home and it lived in our garden. When I went to graduate school as a painter and a printmaker there was a moment when I started to take the paintings that I was making off the canvas and coil them into objects. It was important to realize that I don’t really know where the work ends unless it’s an object in space.

I always think about sculpture as an affirmation. It exists in a really tangible place. Like this chair, for instance, people understand it because it's sitting there attached to a table. I feel like sculpture has that same potential to participate in a very accessible world. It’s this unconventional moment in a very conventional context. The sculptures are almost like mentors. They reinforce this idea of communicating with things outside of ourselves.

Tory Fair, "Campfire Heap," 2016. Installation at VERY gallery, mixed media. Photo credit: Stewart Clements.

SB: In terms of your new work, we met while you were in the process of developing Paperweight which you’ve said feels like an iteration of your previous show, Heap. How are you conceptualizing this progression?

TF: What I did with Heap at Proof Gallery ended up being about marking a place. That was a huge self-reflective moment for me because it tied back into how I fell in love with sculpture as a younger artist. It was like I had created this cairn or notable endurance piece of drawing a huge line on the floor. I got to inhabit Proof as this destination or mountain top that I had climbed and then left a mark on the summit as if to say, “I am here! Thank you for being here, too!” One of the beautiful things I’ve found in the campfire motif in Paperweight at VERY is this idea that I could not only cast real things like objects and trees, but I could also cast the whole idea of a space. The positioning of the logs on the ground became a way to address the residue of conversation and the evidence of something along the lines of a campfire scene.

SB: So when you are choosing objects from your life to put into your work, does the story behind each one become important to the piece?

TF: I was curious when I put Heap up what people would say. I thought they would really press me on the objects like, “Why a mug? Why a basket?” But they didn’t really do that and I’m glad because I think I have this bad tendency to try and find specific meaning in things and it is sort of a philosophical flaw that drives me. I think there is a fine balance to have language that’s not preachy but instead inspires a conversation. The objects in Heap operate in that way. Choosing the objects over time that I bring into the studio has become more of an instinctual way to collapse all parts of my life together as a daughter, a sister, a mom, a wife, an aunt, a professor, an artist, and yes—I vote—a citizen!

SB: Something I’ve been really curious about is this idea of pseudomorphs which we talked about at the studio and has become a source of inspiration for you. Could you explain what a “pseudomorph” is and how it informs your work?

TF: Pseudomorphs is taken from mineralogy: one mineral finds another and through various processes overtakes and inhabits the second mineral’s form while maintaining its own composition. This idea of “false form” is completely analogous to the idea of sculpture for me. In other words, I'm trying to give a renewed sense of form to things that are already out there. Now at VERY, Heap is taking a new form in these campfire logs. Pseudomorph also allowed me to see that I am revisiting myself as a younger artist who had that hunch to go out to the desert. It’s very comforting to feel like you’re still an adolescent searching and asking questions like “Am I an artist or am I not an artist?” Although that might be the least interesting question. It’s more about being exactly who you are.

Paperweight will be on view at VERY Gallery at 59 Wareham Street, Boston, through October 27.

- Tory Fair, detail from “Campfire,” 2016. Installation at VERY gallery, mixed media, 9X8X19.’ Photo Credit: Stewart Clements.

- Tory Fair, “Campfire,” 2016. Installation at VERY gallery, mixed media, 9X8X19′. Photo credit: Stewart Clements.

- Tory Fair, “Untitled,” 1996. Etching, 6X9.” Photo courtesy the artist.

- Tory Fair, “Heap,” 2015. Site specific installation at Proof Gallery, mixed media (cast objects and projected light), 44″X11’X27.” Photo Credit: Julia Hectman.

- Tory Fair, “Untitled,” 1988. Drypoint etching, 8X10.” Photo courtesy the artist.