Two things are surprising about Ethan Hayes-Chute’s project at the List Visual Art Center: it is much funnier than expected, and it is deeply sincere. The show consists of two primary areas: a work bench serving as a backdrop for two short videos, and an installation of a partial cabin that is home to a mix of sculptures and ready-made elements.

Ethan Hayes-Chute

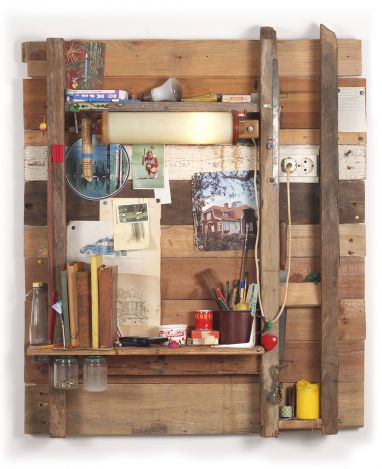

From the series, Structural Slabs, 2015 – ongoing

Wood, found objects, electricity, 82 x 100 x 15 cm

Courtesy the artist

Photo: John McCusker

The didactic literature from the List focuses on aspects of self-sufficiency and self-preservation in Hayes-Chute’s work, highlighting the reclamation of waste and obsolete technologies for practical use. The artist frequently makes small shacks and shelters out of salvaged materials, often filled with found materials that might be of practical use in these cabins if they were located in the woods instead of in a gallery. Certainly, this strategy is present in this show: there are tools, preserved goods, and a utilitarian library scattered throughout—all the trappings of a studio run by a prepper. The tone of the show, however, is not poignant or particularly instructive, and the absurd systems that the artist has created for himself make this brand of self-sufficiency more open and inviting than if he were a hard-line adherent to his own values.

Two Epson HX20 computers in the installation have been modified to run programs created by the artist. The first prompts the viewer to make and print a to-do list with up to ten items. No matter what, the last item on the list (“a courtesy provided by Ethan Hayes-Chute”) is Buy More Pistachios. The second computer, now titled the Egg Collector Pro, has a long slip of paper trailing from it. This list contains visitors’ answers to the survey “How do you like your eggs?” This same type of receipt paper printout is used to label many of the jars and bottles stored around the cabin—a shelf of spices boasts “Mr. Mayo’s Marvelous Mix” and “Hot Mix Dune Spice,” while an area in the back has rows of mayonnaise, nips of what appear to be cinnamon whiskey, and clam sauce (“for clams, from clams”).

Ethan Hayes-Chute

Bottles and jars from Contemporary Spice Rack, 2012.

Jars, bottles various containers, mixed contents, Epson HX-20 printouts, dimensions variable.

Courtesy the artist.

All of the cabin structures, as well as any gallery tables and shelves, are built from unfinished two-by-fours and plywood with visible hardware. The artist is clearly a skilled carpenter, but there is nothing here that requires more than a circular saw and a drill. To that point, Hayes-Chute has made two short episodes of “New Domestic Woodshop,” playing in the gallery and available to watch on conglomerate.tv. Styled after programs like New Yankee Workshop, each video features project instructions. In the first, Hayes-Chute makes a frozen-pizza sized oven out of a reclaimed sheet of stainless steel and two hot plates because he does not have a conventional oven. He completes this elaborate, sometimes inelegant process only to become disappointed with how poorly his pizza fits on his cutting board. “Not only are cutting boards expensive, but the one you want, in the right shape and size for what you want? Nearly impossible to find.” In the second episode, he creates a custom-built board for just this purpose.

Ethan Hayes-Chute

Epson HX-20 Portable Computer, 1982, Epson Corp., Japan, 13/4 x 143/4 x 81/2 in.

These are the kinds of solutions that only come from outlandish work-arounds carried out in a post-industrial, DIY-Until-You-Die mindset. There is an intended practicality: save whatever might be useful, use whatever is around, beat a baseline dissatisfaction by settling less for manufactured goods and making more of precisely what you want or need. Typically the conversation around this kind of work calls into question whether or not it is reasonable—have you saved anything at all if instead of spending money, you have tripled your time and effort? Here, it does not matter whether or not the viewer finds the work practical; the artist clearly knows it is useless. Outside the main gallery is a work detailing Hayes-Chute’s technique for unwinding large spools of paper in order to wind them into smaller ones. “Re-rolling Rolls of Paper Into Smaller Rolls” uses a power drill with a custom bit (a dowel labeled “paper winder”) to complete the task. The drill sits on top of a small television that plays a seven and a half minute long video demonstrating the process. Presumably, all this work is carried out to provide the artist with rolls of paper that fit the two computers in the gallery, one of which, again, is running a program that just asks visitors how they like their eggs.

All these layers of unnecessary work are what really sell the installation. It looks less like set dressing when the scales are tipped towards humor, and the artist presses on despite the potential futility of it all. Hayes-Chute’s website is divided into two categories, Arts and Leisure. The first is documentation of other works like the cabin on view here, but the second has links to his ASCII art, an all-MIDI radio show, and photo journal that documents how he and some friends found and restored an abandoned boat in the summer of 2005. The boat project is not that different from an episode of New Domestic Woodshop, nor should it be. This is a person who, in the studio and out, appears to live with a commitment to experimental solutions bound by an economy of means. This is precisely the kind of person who can point to new futures for artists that do not scrimp on the role of deep creative thinking in utilitarian projects. It looks to be a good life, and a fun life, and all are welcome to make a to-do list and get on with it.