The sculptures in VERY’s inaugural show, Sex Not Sex, inhabits the space in much the same way as the patrons at the opening: some sitting, some standing, others propped against the wall. In a gallery that feels more like a family room than a white cube, the work of Arthur Henderson does not simply provoke discussion but quietly joins the conversation. A graduate of MassArt and now based in Connecticut, Henderson makes objects that are perverse, playful, and recognizable, constructed with a slew of different materials that all together nudge us towards the artist’s concern with gender.

Despite drastic variation from piece to piece, a humorous underpinning creates continuity throughout the exhibit. Moments of the show gave a nod to Phillip Guston’s representational paintings but Henderson’s relationship to Guston and to cartooning tend to be more theoretical. In an interview with VERY owner, John Guthrie, Henderson describes cartoons as “a shorthand form of abstraction,” a vehicle that facilitates the communication of narratives and information. More than anything, though, cartoons allow Henderson to push beyond the limitations of realism.

Arthur Henderson, TEAPOT, 2016, 12 x 10 x 14", wood and wax. Photo: Stewart Clements.

Behind each of the forms is pointed intentionality: Henderson chooses a gender for each of the works before he begins. According to text provided by the gallery, some pieces are both male and female. For instance, sitting on a coffee table is “Teapot,” a hand hewn and polished pine teapot that roughly resembles an oversized head. It’s humorous, awkward, and fully functional. The vessel’s spout becomes a nose in profile or a phallus protruding from a womb-like body. Though sophisticated and suggestive, the piece remains approachable and unassuming under Henderson’s sensitive craftsmanship.

Lying on its side in the middle of the floor is perhaps the most inconspicuous sculpture of the bunch, “Maid,” a wooden milk crate. Like “Teapot,” Henderson uses carving, a process he deems masculine, to produce an object that symbolizes femininity and maternity (i.e. a container that carries a life sustaining substance). The crate is an impressive copy, yet no matter how precise the representation, “Maid” will never be its referent. Like a painter attempting to represent his muse, Henderson objectifies what he sees as feminine in the real world and only achieves a beautiful imitation.

Arthur Henderson, VENUS, 2016, 48 X 39 X 15", polystyrene and paint (install shot). Photo: Stewart Clements.

Henderson’s sympathy resides chiefly in his female forms. He views the female sex as life-giving and life-saving. The latter interpretation comes through literally in “Venus” which is made from a floatation device, a large chunk of blue polystyrene with giant white hands extending from the sides. Despite the mythological reference to the perfect woman and the welcoming gesture, the piece repels notions of beauty. Henderson cannibalized the surface through a number of processes so that the synthetic foam appears weathered as if it washed ashore in a storm.

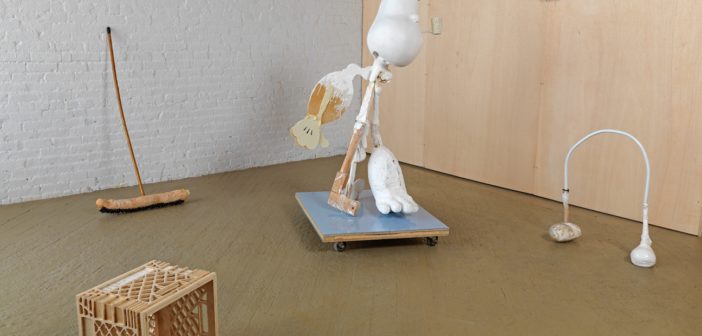

The male gender gets much harsher treatment throughout the show as Henderson grapples with his own male gaze. Standing pitifully yet proudly upright with life-size gait is a sculpture called “Poyrboy.” It is unmistakably Popeye—the iconic cartoon sailor and epitome of hyper-masculinity—though he is only identifiable by the silhouette of his head and his pipe which cannot escape Freudian connotations. The rest of the form is stripped down, cobbled together with broken joints and doused in chalk white paint. He has no eyes and a penis without testicles. It’s a brutal conception of the male form: blind and infertile.

Arthur Henderson, "Sex Not Sex" at VERY, 2016, Install Shot. Photo: Stewart Clements.

Henderson’s tendency to emasculate his male objects plays into his underlying motive to make his sculptures approachable. His work is about disarming the viewer to open up channels of thought rather than discouraging individual interpretations. To lay the pun on thickly, there is no work more “disarming” than “Gub,” a rifle made from French stone and tar that borrows its title from Woody Allen’s flunked bank robbery in Take the Money and Run. Sticky, black, and limp, “Gub” packs no heat and hangs on the wall like a charred relic. Despite knee-jerk reactions to the symbol, Henderson subverts our expectations with a gun that lacks all bravado.

When faced with questions about his work Henderson does not fill in the blanks. Later in the interview with Guthrie, Henderson says, “Art is not a puzzle to be solved,” reminding us that the artist is not the oracle containing all the answers. It would be easy for a show with so much psychological baggage to drag us quickly into didacticism. Fortunately, in Sex Not Sex, Henderson handles the touchy subject of gender by insisting on the viewer’s personal experience and allowing for a spectrum of readings.

Gender is as familiar and unfamiliar to us as the objects Henderson creates. From a distance we may believe we can name what we’re looking at—a crate, a teapot, a gun—but a closer look begins to break down our sturdy understanding, giving freedom and new life to the forms.

Arthur Henderson: Sex Not Sex closed on July 14. Stay tuned for more information on VERY, a new gallery at 59 Wareham Street in Boston's South End.