The Woven Arc, an exhibition at Harvard University’s Ethelbert Cooper Gallery of African and African American Art, demonstrates the important role that textiles have played in the history of art and continue to play in the contemporary art world. Director Vera Ingrid Grant’s curatorial statement describes the works on display as “an unusual selection of artworks not usually posed in conversation with each other.” What connects these works most compellingly is their engagement with the textile tradition–a tradition with strong roots in African art that extend to the contemporary art of the African diaspora.

Textiles are unique is that they permeate our everyday lives. We wear textiles on our bodies; they adorn the private spaces of our homes as rugs, curtains and bed linens; and they are found throughout public spaces in a wide range of forms, from seat covers on trains to curtains at the theatre. The intimate connection of textiles to our lived experience is what gives them so much meaning, and it is precisely this meaning that is explored by the artists in The Woven Arc.

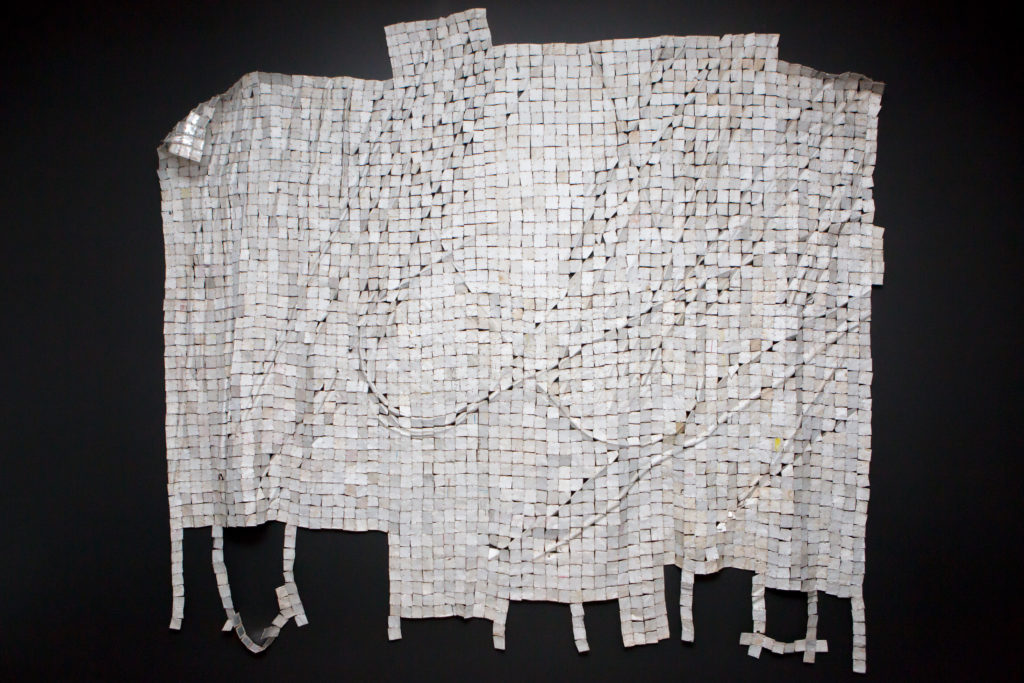

El Anatsui, Metas II, 2014. Photo Credit: Melissa Blackall.

The Woven Arc is an innovative show in the way it demonstrates so clearly that textiles are equal to painting and other art media in their potential to raise poignant questions, address complex histories, and reflect upon the quality of our lives. If there is any drawback to the exhibition, it is in the limited information about the artists and their works made available to the visitor. The list of the thirty-three works on display only offers basic information. Visitors unfamiliar with the artists or these specific works will be dazzled by the beauty of the textiles on display, but might miss out on some of the most nuanced questions being raised by the works.

The exhibition is not theme based or arranged chronologically. Historical textiles are mixed with contemporary works based on their relationships to each other. Several historical textiles strategically placed throughout the exhibition provide keystones for viewers, grounding the show in the African textile tradition. At the entrance, four nineteenth-century aprons illustrate Ndebele mastery of beadwork, using it to decorate their clothing with abstract designs. An early twentieth-century Kente prestige cloth serves to recognize this centuries-old West African weaving tradition. Traditionally worn by royalty, kente cloth gained widespread use as a popular form of dress for men and women. An Adire wrapper from the 1960s acknowledges the importance of a technique of resist-dyeing on factory-produced cotton practiced by Yoruba women. This technique results in rich indigo fabrics initially used to make garments for women, and by the 1960s, for men as well. These historical textiles are foundational as they set the stage for the use of textiles by a diverse group of contemporary artists.

A sculpture by British-Nigerian Yinka Shonibare, a now well-established artist, opens the show. Shonibare has been using batik in his work for several decades to symbolize the history of colonialism based on the migration of batik from Indonesia to Africa and America through trade with the Dutch and British. Shonibare’s Food Faerie (2010) appears whimsical until we notice that this hybrid, winged, child-like figure is headless. The history of colonialism is evoked in other works as well. Six by Six (Slaver Logbook) (2013), by South African-born Peter Sacks, is comprised of nineteenth-century European fabrics combined with African fabrics and written text related to slavery, all covered in white acrylic paint. Upon first glance, this work might be mistaken for an abstract painting but a closer look reveals the written materials and textiles—including a prison shirt—challenge the viewer to construct an historical narrative from these disparate pieces of history. Tim Rollins and K.O.S. (Kids of Survival) take a similar although more straightforward approach in Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (After Harriet Jacobs) (1997), in which colorful ribbons are carefully draped over the pages of Jacobs’s narrative, leaving plenty of space between each ribbon to reveal the text. The exhibition includes four paintings by Lina Iris Viktor–a muti-media and performance artist raised in London by Liberian parents. Working strictly in blue, black, white and 24-karat gold, Viktor draws on diverse sources ranging from Egyptian hieroglyphs to Byzantine icon painting and hip-hop culture, all combined to create powerful female figures. Although alluding to historical figures, she brings her subjects into the present by inserting her own image into the environments that reference them. The empowering images and dynamic energy of these paintings provide an important balance to other works in the exhibition that address the oppressive history of colonialism. Yaa Asantewaa (2016), the title a reference to the queen mother of Ejisa who led a rebellion against British colonialism in 1900, and Syzygy (2015) are both beautiful and powerful paintings in which textiles take center stage as expressions of fashionable adornment.

Lina Iris Viktor, Syzygy, 2015.

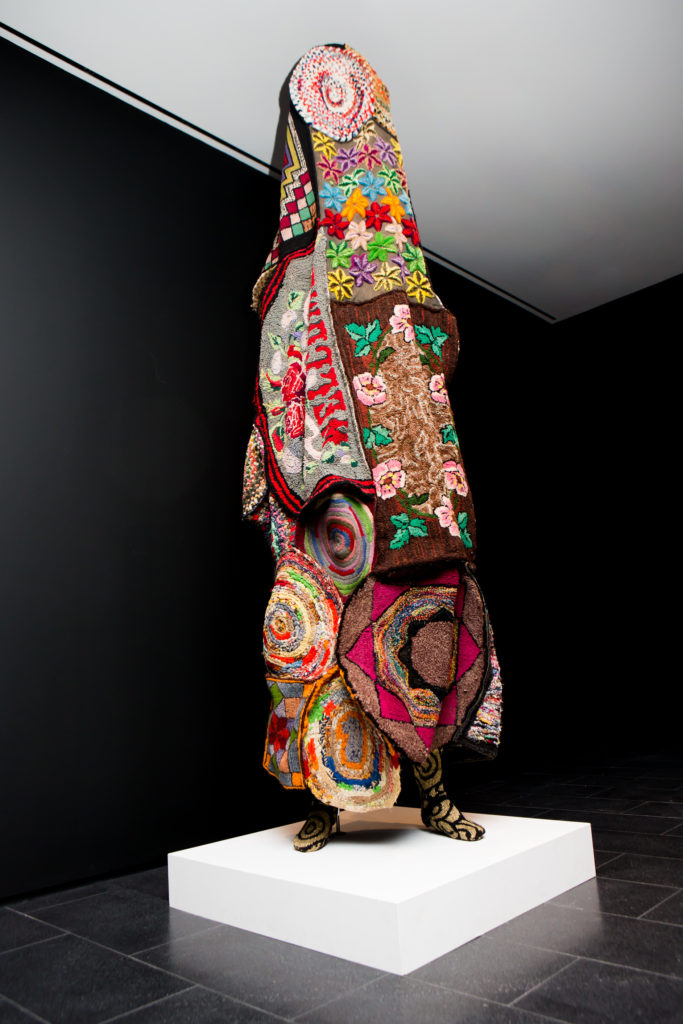

El Anatsui, born in Ghana but active in Nigeria, is another well-established artist in the global art scene. His wall hanging Black River (2007) is currently on view at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and a movie about the artist, titled Fold, Crumple, Crush, was released in 2011. El Anatsui creates glistening wall hangings from found materials like bottle caps and metal wrappers that are woven together in a way that evokes West African textiles. The wall hangings are designed to move off the wall in an expression of dynamic energy, just as textiles worn as clothing move with the body of the wearer. An interesting floor piece by the artist is included in the show and paired with African American artist Nick Cave’s Soundsuit (2011), made of hooked rugs. The pairing makes a playful juxtaposition, reinforced by their connection to the floor. Both artists use found objects, but Cave’s soundsuits are meant to be worn. A second Soundsuit (2010) by Cave is also on display. Boston audiences may be familiar with Cave’s work from his 2014 exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA). Although playful in the choice of materials, the suits were originally inspired by the Rodney King beating and the ensuing Los Angeles riots of 1992. Like El Anatsui’s sculptural forms and many of the other works in the exhibition, Cave’s soundsuits originate from the common materials of daily life. Transformed by the artist, they provide compelling commentaries on a wide array of social issues.

Nick Cave, Soundsuit, 2011. Photo credit: Melissa Blackall.

While many works in the exhibition allude to the importance of textiles as a form of body covering, Kenyan-British artist Grace Ndiritu takes us directly to an exploration of the meaning of textiles in relation to our bodies. Still Life/Textiles (2005/2007) is composed of four five-minute videos in which partially exposed bodies respond to the fabric that covers them. In the segments Green Textiles and White Textiles, colorful patterned fabric dominates the monitors on which each video is shown, while a person largely hidden from the camera thoughtfully and gracefully runs hands and fingers over the fabric hanging in front of them. These videos are lush and sensuous. Between them are two additional segments that directly relate to the painting tradition not just by the titles, but by the subject as well. Still Life (Sitting) focuses on a seated figure wrapped completely in fabric; the composition is reminiscent of so many paintings of this subject, while the wrapping of the figure resists the viewer’s gaze. Still Life (Lying Down) also highlights a figure wrapped in fabric, this time in a reclining pose that recalls the long tradition of painting the reclining female nude, but again denies us access to the figure’s body. In both cases, there is only very subtle evidence that these so-called still lifes are in fact composed of living people: the gentle breathing of each figure evident only upon close inspection, the humanness emerging in spite of, or perhaps the result of, the figure’s immersion in such beautiful fabric.

Ndiritu’s The Nightingale (2003), a seven-minute video, is placed in a separate room from the other Ndiritu videos, appropriately displayed with a variety of nineteenth and twentieth-century African headwear. The video starts slowly; a figure covered in a brown patterned fabric stands in front of the camera, barely moving to the beat of the music that accompanies it. About halfway through the video, the pace of the music suddenly quickens at the same time that the fabric transforms from a body covering into a red patterned head covering that is masterfully manipulated into a variety of forms. Through this manipulation, Ndiritu invites us to consider the various types of head coverings worn by women across the globe. The commanding way in which she controls the fabric implies the power of women to determine how they cover their heads. In the same room as this video, a beautifully beaded twentieth-century Yoruba Crown is highlighted in its own display case, a marker of headwear as a symbol of power. In dialogue with Ndiritu’s video, the crown, caps and other hats in this room raise questions about the politics of headwear.

The Woven Arc provides an excellent opportunity to contemplate the nature of textiles as a form of artistic expression. The show directly engages the tradition of textiles specific to African and African diasporic artists. But it does not end there. More broadly, the exhibition calls for reflection on the meaning of textiles for all of us. In its global approach to fabric, The Woven Arc transcends cultural boundaries, just as the textile works themselves transcend the boundaries of art.

The exhibition is on view until July 16, 2016. The Cooper Gallery is located at 102 Mt. Auburn Street, Cambridge, MA.