In his new “Instant Traveler” show at Clifford Smith Gallery, Youngsuk Suh displays a large-scale photographic series of magnificent national park settings in Hawaii. The stage is what one would expect in such a paradise: the water is cool and inviting, the clouds are heavenly, and the greenery, long since absent in this part of the world, is lush and intoxicating. Even in the distance, the volcanic mountains speak turquoise and maroon, we all wish we were there, because we like nice things.

But things are not always how they appear. While Suh expresses the undeniable magnificence of the Hawaiian terrain, he also pinpoints a far more sophisticated element: the constructed ways of seeing. Reaching back to Carleton Watkins in the 1860s and most notably with Ansel Adams in the 20th Century, the photography of the Great American Landscape impressed upon its viewer awe for the undisturbed environment, justifying its use as a natural spectacle rather than as a resource for industrialization.

Suh states that this “preservation of so-called nature is a manifestation of a highly developed civilization.” In regarding the phenomenon of the national park, the physical landscapes offered become celebrities in themselves, a visual reflection of a popular image. Who has not already visited Yosemite on dozens of occasions as a tourist of photographs, an instant traveler? However, to travel there in person demands a certain comparative proof to the photographed Yosemite, the Yosemite of our imagination.

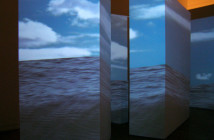

Along these lines, Suh has often laid down certain rules in the photographing these parkscapes. One includes not traveling more than ten minutes from the parking lot in order to find the most convenient vista, the nod to the car that the national park experience cannot avoid. Another involves staying in one spot at length to make multiple images of the same scene. In the process of image making one can imagine that Suh himself blends into the setting, the trope of the photographer with his large format camera against the heroic landscape, but the process of output is a resoundingly contemporary one.

After photographing the same scene in multiple, Suh then scans his negatives and is able to add, subtract, and exaggerate certain elements in the computer to construct a composited digital iris print. As a result, the viewer is left unsure as to what Suh has manipulated and what is “authentic” about the landscapes. Is Hawaii really so green?

One aspect that is certainly altered is the placement and frequency of people. “Wainapanapa, Hawaii” presents a beach scene enveloped with lush plants and people scattered all over the famous black sand of the Hawaiian seashore. Each person in this scene is filled with individual purpose: wading in the water, snapping photos, hiking along, investigating or discovering something or other. Interestingly, none of the people acknowledge or respond to each other or the camera, they are each lost in their own world of sensation. With the hand of the artist certainly at play here in bringing people perhaps hours apart into the same scene, the artist’s intentions ring clear. Unlike Watkins and Adams presenting a pristine nature devoid of human interference, Suh focuses on the mediated yet personal encounter of people within a landscape. His photographs speak loudly to the experience of nature, rather than to nature itself.

Suh’s people are uniformly small in scale and without identity, representations of the universal human and their general activity. “Kipahulu, Hawaii” is a scene with greenery, waterfalls, pools, cliffs jutting out and a few dozen people milling about. It is reminiscent of traditional Asian calligraphic paintings where a heavenly landscape is often met with a few minuscule human figures journeying about. As the scale of the people in these paintings serves to further revere the grandeur of the landscape, the same is true for Suh’s photographs, his people make his landscapes that much more impressive. Four images of Haleakala National Park in this series further emphasize this point.

Here, clouds make up a majority of the images of the vista off a mountaintop; people are again tiny, but one gets the sense that they have journeyed to reach this point. It is as if tourists travel great distances in order to feel small, that there is a basic need to feel reduced in the presence of the magnificent. Suh has infused this same need in the viewer, we want to replace the characters in the images, we want to feel small too. In his series of photographs, Suh has come to approach his subject with one of the rarest commodities in contemporary art: humility.

- Kipahulu, Hawaii, 2003; Iris print.

- Haleakala National Park, Hawaii, II, 2003; Iris print.

- Wainapanapa, Hawaii, 2003; Iris print.

----

Links:

Clifford Smith Gallery

Instant Traveler

Youngsuk Suh's "Instant Traveler" is on view March 5 - 27, 2004 at Clifford Smith Gallery.

All images are courtesy of the artist and Clifford Smith Gallery, Boston.

Benjamin Sloat is a regular contributor to Big, Red and Shiny.