Lisa Yuskavage is one of the very best and most highly acclaimed painters working today. Mainly known for her lavish and sometimes lewd renderings of the female form, Yuskavage’s work has an unforgiving and forthright style that combines elements of high and low culture bound together with a knowing technical virtuosity and an encyclopedic visual memory. A comprehensive survey of her work over the last several decades, titled “The Brood”, is on view at the Rose Museum at Brandeis University until December 13 and then will be traveling to the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, in St Louis on January 15 through April 3, 2016. We spoke over the course of several days recently.

Robert Moeller: Regarding the controversies surrounding your work, do you see this as part of the paternalistic attitude about what women can and cannot do, and in your case, what a female artist can depict? Has anything really changed in this regard?

Lisa Yuskavage: There are entrenched prejudices against all things female, and those expressions can come not just from men but also other women, even in the name of feminism. That qualifies as misogyny. But there are many excellent woman artists working today who are embraced warmly and so I don’t see this is a global issue. At this point, I am willing to say that I think the controversy is actually more specific to me, and my energy, and I believe it comes from a number of elements in the work. First issue is the potency and specifically female potency that I seem to both personally represent and also inject into my paintings. I do not create work from a warm and fuzzy place. I am representing something vulgar, harsh and sinister (at times) and these are not on the list of things we allow women to say or to be. That is certainly a gendered prejudice. Men suffer under no such prohibitions.

The paternalistic, didactic and prescriptive seems to come into play because I do not paint in a manner grounded in expressionism. This mode of representation would make the work a safer repository of emotion. I chose a manner of constructing a painting that allows for the huge carnival of emotions that I seek to represent, anger being only one of them, but also love and tenderness and humor, loneliness, self-deprecation, internalized misogyny, grief and joy... the whole banquet table. The manner in which I paint allows for this range. I have given it a lot of thought over the years, and if I did paint in an expressionist manner it would dilute the potency.

RM: In regard to the range of emotions you describe, are these all available when you begin a painting or do they somehow become more tangible as the work unfolds? Or more practically speaking, what goes where?

LY: Usually when I start a painting I have an inkling of a very specific combination of things that relate to things from several points. Usually a collision of things I find or see or remember, and it usually has a root also in some other kind of artwork somewhere out there too. Such as, back in the mid-nineties, working with the “Bad Habits” maquettes, I wanted to find a way to work outside of my imagination and have something to observe, and I remembered that Tintoretto did something like make wax maquettes and put them in boxes and lit them with candles and studied the light. I was also remembering something about Guston and his endless use of gerunds with Smoking Eating Painting. I started with remaking an image that existed from a painting that was in the studio at the time, Faucet, and sculpted her in Sculpty as child's clay. And then went on to give her a posse and ended up with the characters: Asspicking, Foodeating, Headshrinking, Socialclimbing Motherfuckers. While working out the images three-dimensionally, I was connecting to funny, playful and sometimes hateful memories. It was overall a grand time creatively, as there were endless ways to work and rework those images.

Now I don’t work with models. Nor sculptures. I work rather synthetically, which is to say I do all sorts of things and pull from all kinds of sources including my imagination. I like layering the image and idea without letting it become a collage. I allow for the meaning to be mysterious to me. I never demand an explanation from myself, and try never to foreclose on any possibilities. When it is right, I just know. I hate to leave you high and dry with this… but sometimes the process is just magical. And often I just get lucky. I put things in and take things out of a painting endlessly and allow my bullshit detector to edit. I also try to find something on both a formal and image level that surprises me. I often make a painting that I wish someone had already made, but they didn't, so I have to do it.

I have worked seriously on developing an emotional range. What content or type of picture making would not be right for me? Well, you won’t see it because I would edit it out. And I never let it out of my studio.

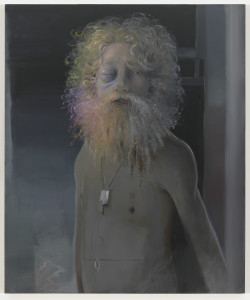

I have a couple of paintings that I just recently unearthed from 1991-1992 of two boys that I made when I was making the “Bad Babies.” They were leaden, dead on arrival. I put them away in my painting racks and only recently took them out to show a friend because of the nude male in my most recent show at David Zwirner. The difference is that they were not at all alive. The new Dudes were definitely full of feeling…

Lisa Yuskavage

Dude of Sorrows, 2015

Oil on linen

48 1/8 x 40 x 1 5/8 inches (122.2 x 101.6 x 4.1 cm)

Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York/London

RM: Speaking of painting the male figure, what's different if anything in your approach? Is it more difficult setting up the interior life of the subject? Or on a certain level, is it similar to depicting the female figure? Or this an unfair question, rarely asked of a male artist painting the female form?

LY: It was harder to find my way into a male character in an authentic way. The first significant man is in The Brood show, called The Feminist’s Husband [painted in] 1996, but he was less developed and never appeared again. Then in about 2008 I made a small painting called Tourist and a guy appeared in the background rather spontaneously without me willing him in. He simply appeared out of the act of painting. This is an example of the important role the small paintings have in my work… their ability to allow me to find images in the paint and then later claim and develop them further. So in that painting when I looked at the little fellow, I realized, with pleasure, that he was not just a man but also more specifically, a tourist. He had gotten lost and accidentally wandered into my work. I loved that and I claimed him. And then worked with the tourist man, the traveller man, and the journeyman for a while but they were more secondary figures. I was trying to find a way to let them be in my work. And a few years ago, for some unknown reason to me, when I found out that gay men had a phone app called Grindr. I thought it was amazing that a person's id could get linked to their GPS. I downloaded it and made up a persona and almost hooked up with a dude till I realized I was not a dude. I deleted it right after that because I thought I was getting weird. But later when I made Dude Looks Like Jesus I had the ability to inhabit the identity of a man because of that experience. I used that and it was fun. Then with the Dude of Sorrows I was able to continue to think as this older, more dilapidated kind of man. It was fun. When I first started to paint women, it was important to me at the time to stop being “dopey Lisa” and I decided to inhabit the character Frank from Blue Velvet. I did not paint him but painted as him. I made the painting The Gifts in his persona. He was super creepy, but it beat being me in the studio. There was more room for painting.

RM: What you are describing is a performative aspect of painting rarely discussed, a sort of absolute, gut-level change in how painting is generally talked about. Can you expand upon how these personas take over a work?

LY: I am more inhibited than one would think I am. So I need strategies to open up. I am a not-so-smart, working-class kid aware that there is such a thing as high art and high culture, and I don’t feel I have a place in it, so if I go into the studio as that person, I bomb. I need to leave that persona aside and much later I can let her in too. I have a big investment in the idea of multiplicity. I actually decided to go ahead and make a painting directly about it called Hippies. The idea of multiplicity in psychoanalytic (from Philip Bromberg’s Standing in the Spaces) thought took over from the id/ego/superego tripartite idea/structure. I like multiplicity because it means that we each have an endless array of possible characters inside us that, if we are mentally well, all can interact and we are aware of them and they play their given role. I could not find the male voice until I could name him more specifically and more authentically. I don’t force the character out, it usually starts with something subtle and I develop it and develop it until it feels very vibrant and real. The Dude of Sorrows found me. The painting was seriously sucking, and then I set it aside and started it over and was experimenting with stuff, i.e. beating up the original canvas. And it (the canvas and the Dude) loved it. He got more magnificent as I beat on him/it. It was magical. He got a whooping and turned it into beauty. Or rather I did.

Also, and all of this goes back to a critique I had in grad school with William Bailey and he was barking at me that the problem with my paintings is that I believe that they are real. He quoted Magritte’s painting to me “Ceci n’est pas une pipe, Lisa,” and I was sulking, but thinking to myself, what else can I do? It’s how I do things—I need to think of it as real! And out of the crowd (the famous Pit Crits at Yale) came John Currin and he said, ”Excuse me but I actually think it's wonderful that she thinks it's real.“ Kind of an important moment of finally being truly seen and in finding a peer.

Lisa Yuskavage

The Ones That Can’t: Tea, 1991-1992

Oil on linen

26 x 24 inches (66 x 61 cm)

Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York/London

RM: One of the most striking aspects of your work is the almost chemical-like use of color. The figures you paint inhabit these richly saturated color fields that in a sense form the armature supporting (and protecting) the entire ecosystem of each painting. Can you talk about the role of color in building out these environments?

LY: I think your question is more of a lovely answer than I might even give you. So, how do I do it? If that is the question I have a couple of ways to answer it.

Growing up in Philadelphia, there was a lot of impressionist and post-impressionist paintings. I stared at those paintings at the Barnes and at PMA from high school onwards and then was lucky enough to go Rome as a third-year student at Tyler. This is not typical of a working-class American in the 20th century. I traveled and looked very hard at Italian art from early frescos to High Renaissance paintings. I think I began to see a relationship in the southern attitude toward the color in shadows. It was luminous. I then began to study color theory on my own by reading in the library everything I could find from Goethe, Itten, Munsell and anyone who wrote about it. I liked Itten best. He is rational, but a lot left room for intuition. I began to see that color was a code and a clear system. Between reading and looking, I decided to upend what one thinks color should do. I decided to attempt to make paintings using a system based in Cennini also known as "up-modeling." That is pure color in the shadows and everything is up from there. He was actually describing frescos because fresco doesn’t do dark well. I adopted that and the luminosity of southern French color like Monet and late Van Gogh to push the emotional tone of the work. Intensity and luminosity in shadows bring a certain hyper-reality. Also, the works are based on contrast to bring the meaning and emotion to the fore. In some cases, it is the contrast of warm and cool or in the bright and dull, etc. The opposite of contrast or Harmonious or analogous color is also a big player. Green on green on green on green in varying intensities and shades and temperatures and densities also bring a strong feeling to the viewer, with the first viewer being myself in the studio. I know they are not always pleasing to the eye, but I hope they are eventually pleasing to the mind. I also allow for color ideas that come from many low sources such as Laura Ashley color theory and other places.

RM: Laura Ashley? That's amusing. I wouldn't have guessed you were looking at commercial paint swatches or decorating tips. And yet, it makes perfect sense in a very subversive way.

LY: As for Laura Ashley, I was teaching painting and had just taught the color wheel and had just mentioned to the students that it was hard to make a painting with the primary color triad and they asked why and I said because red, yellow, and blue have nothing in common. Later that day, I got a catalogue from Laura Ashley in the mail and saw how she was pushing the idea of “her signature” red-yellow-blue palette that could be mixed and matched any which way, even floral patterns, stripes and plaids. I read further and she said it was due to the modifying of the colors to create similarities. Then I remembered that Maria Hall in her amazing book Color and Meaning in Renaissance Painting talked about a type of color idea used by Raphael called Unione. It was the same idea. I then premixed my own signature tubes of red, yellow and blue and made Blonde, Brunette, Redhead. It all just connected.

Lisa Yuskavage

Blonde, Brunette, Redhead, 1995

Oil on linen

Triptych

Overall: 36 x 108 inches (91.4 x 274.3 cm)

Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York/London

RM: Your website is pretty impressive, archival even. Is this part of a process that involves looking back and taking stock of what you've accomplished so far?

LY: The website came last. A Filemaker-based database came before. But it all got started sometime around 2005. I noticed the poor quality of the projections of my paintings in PowerPoint. My work has a lot of close color and the nuances were getting lost completely. Out of complete despair that this would be the fate of my work in the digital world, I began to ask a lot of people who are knowledgeable about this new sort of documentation, and found out the way things needed to be rescanned, drum scanned or reshot digitally. That has been an ongoing project. But prior to that all, I had been keeping track of the work via a sort of old-fashioned archival method where I would put a slide into a special index card and write whatever was pertinent, size, title, etc... and put it in a box. Now that things are no longer analog, the issue of how to store and organize all the digital files came up. A young woman, who is now my database guru, offered to help me create a custom digital database. She and I came up with a way that the database (Filemaker-based) could be endlessly customized to reflect my thinking and the needs of my work. There were diptychs and triptychs, for example, that had been broken up over the years for various reasons and I realized that if I were to die that no one would ever know the connections I had made over the years, especially the early works. So we made buttons for that type of connection and identification. I also wanted to have ways to show someone someday how I made works that relate to each other, in some cases quite simply, as in a study or a drawing or maybe there are works that I thought of as connected that no one otherwise would see. For example, the most recent painting that we are debuting in the CAM St. Louis venue of The Brood is called The Big Pileup. I have connected it to many works and it shows the way I think through work in a non-linear way. There are also keywords or taxonomy and that is just to reflect again some actually pretty intuitive ways that I discuss or think about the works. This is all a living and breathing thing. There is also something I wanted which are states of the painting... if I have them... and also source materials where I have them. Most of this will not be live on the website but will be available for research for the future. This is meant to be a record of the work as a living thing. Christopher Bedford entered my studio just as I was beginning this process of the database. I was showing him how it worked and the idea of pushing a button and finding “all diptychs” and he and I got the idea for the show that is at the Rose Art Museum now. We could see that this kind of work layered almost perfectly across the mature period of my work too.

But as for the website, I was really, totally against it for a long, long time. I did not see a reason for it. But then I turned 53 and this database was so cool and Filemaker made something you could then make your database as a backend for a website. So I found a boutique team of web developers and I said I wanted it to be an Alice in Wonderland type experience. Open a door and then another one pops open. And it keeps going.

I guess this reflects that I had the opposite of a midlife crisis. I decided it’s wonderful to have this amount of work to look back on and it might be a nice thing to share. I have been meeting up with younger artists that told me that my work meant a lot to them when they were kids etc... and I just thought it was time to share the information and it was important to me to do it without editorializing. We put all information including both good and bad reviews… and maybe even art I am not so proud of, but the fact is that I made it 30 years ago and it might be helpful to see that progression, and the failures, too.

I also love the idea of connecting to a person who is isolated and lonely (as most young artists are) in some part of this country or maybe someone who just got away from some repressive country and accidentally finding the site. They have the freedom to spend a lot of time lurking and playing in there and seeing what I have done as possible. And I hope they do even better than I have done as far as being free. And I hope I meet them someday. And if they don’t like my site, they can click on over to another artist’s site. It was just that simple in the end.

Lisa Yuskavage

Bonfire, 2013-2015

Oil on linen

Diptych

Overall: 82 x 133 inches (208.3 x 337.8 cm)

Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York/London

RM: Has the Internet changed the way that an artist looks out at the world and gathers information?

LY: I remember going to the New York Public library in midtown where they housed most of their art books and a wonderful collection at the “Library’s Picture Collection”. It was an interesting resource to find things to match some of the ideas I had in my imagination. I should go there still. And now that I said that I will. But yes, the Internet has changed the way I have looked for images. It is both better and worse. The presumption that everything is there is incorrect. I know that. I remember how great libraries are. I hope younger artists will spend some time digging around in stacks and pulling out bound periodicals of Art News from 1968-1975 or whatever and see how things were then. I also used to go to lots of old magazine stores and don’t do it so much anymore. It is less the Internet and more the digital revolution that has changed things.

RM: The Brood not only is the title of your most recent exhibition, it is also the title of a new book devoted to your work. What was that process like and how difficult was it to sort through what amounts to a career's worth of material and reevaluate it all?

LY: Actually the title is originally from the David Cronenberg's movie, The Brood. I have used the plot of that movie as a short cut to explain the way the work is out there behaving badly on my behalf. The thought of the work being troublemakers is appealing. It reminds me of the idea from the 19th century that an artist should be the most genteel, perfect bourgeois in life and a bohemian only in the studio. I first heard of it in a class in undergrad at Tyler School of Art with Dr. Dolan who is a Manet expert. Her teaching on his paintings and the critical writing around Manet during his lifetime has had a profound influence on my thinking.

The show and the book and the database/website project have been a big unearthing of many boxes of ephemera: notebooks, source materials, etc. Things that I had just stored away all these years. My mom pitched in and sent me a bunch of stuff she had scrapbooked. The database project having been so far along by the time we started on the book made the book richer and more fun. One of everyone’s favorite pages in the book is page 92. It a page from a lined copy book I kept in 1989, way before I was even ready to make those “Bad Babies.” It kind of surprised me that I made that scribble three years before getting the nerve up to paint like that.

I did a book signing and talk at Tyler this month, and a lot of my extended family showed up to get the book signed. A few days later, I got a call from my mother’s sister, who was laughing so hard I think she was crying. She could not believe the fact that there was a photo of my mom (at age 18) in charm school on page 92 that I used as source material for Big Marie. It was rather gratifying to look back and see all the work put together both digitally but also the way the book and the show came together. You cannot fake your own history.

- Lisa Yuskavage Babushkas, 2010 Oil on panel 8 x 6 x 1 inches (20.3 x 15.2 x 2.5 cm) Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York/London

- Lisa Yuskavage Big Little Laura, 1998 Oil on linen 76 x 96 inches (193 x 243.8 cm) Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York/London

- Lisa Yuskavage Night, 1999-2000 Oil on linen 77 x 62 inches (195.6 x 157.5 cm) Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, New York/London

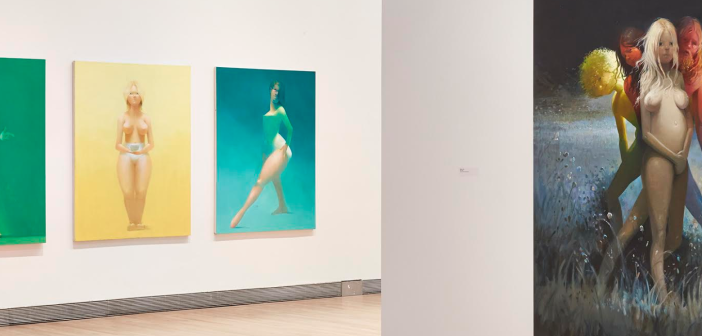

- Lisa Yuskavage: The Brood (install). Courtesy Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University. Photography-Charles Mayer.

- Lisa Yuskavage: The Brood (install). Courtesy Rose Art Museum, Brandeis University. Photography-Charles Mayer.