“Imagine a vast sheet of paper on which straight Lines, Triangles, Squares, Pentagons, Hexagons, and other figures, instead of remaining fixed in their places, move freely about, on or in the surface.” Thus begins Edwin Abbott’s 1884 novel Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions, which reduces social classes to geometric forms, the more sides the higher the class. Touch is the primary faculty of perception in the novel. The narrator explains, “Our sense of touch, stimulated by necessity, and developed by long training, enables us to distinguish angles far more accurately than your sense of sight.” A common greeting in Flatland is, “Permit me to ask you to feel and be felt.” One must feel another to truly know his contours.

The 24th Drawing Show at the Boston Center for the Arts, Feelers, takes its name and conceptual framework from Abbott’s novel. The drawing biennial includes sixty works by fifty-six artists in the Center’s Mills Gallery. All hew closely to the themes of line and touch, transcending a condition of flatness that the exhibition takes as drawing’s essential condition. In this sense, Feelers offers the inverse of Michael Fried’s 1967 Artforum article “Surface and Illusion,” which praised the way Ronald Davis achieved a painterly effect of flatness even in the sculptural media of plastic and fiberglass. The focus on surface and touch helps decenter visuality’s privileged role within the sensorium. In the same vein, Helen Molesworth, curator of Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933-1957, currently on view at the ICA/Boston, claims the haptic as the defining feature of the college’s pedagogy. Thinking about haptic vision, however, is not a recent phenomenon.

Photo credit: Melissa Blackall Photography 2015 Liz Nofziger Ground Lock, 2015 Variable dimensions Translucent vinyl

In the fifth century BCE, Empedocles imagined feelers (light rays) jutting out of our eyes and into the material world. The Paragone debates that raged in Renaissance Italy pitted sculpture against painting and circumambulation against static viewing. For Alois Riegl in the late-nineteenth century, ancient art was haptic, while modern art was visual. In the mid-twentieth century the French art historian Henri Focillon and his student George Kubler developed a theory of form based entirely on touch. Kubler declared, “Our ways of describing the visible past are most awkward.” He turned instead to the tangible shapes of time: “Like crustaceans we depend for survival upon our outer skeleton.” Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, Jacques Derrida, Jean-Luc Nancy, and many others have weighed in on this dialectic of haptic and optic sensation. Though their conclusions vary, they all argue that touch has enormous force in both constituting and disrupting the faculty of sight.

The works in Feelers, most made in the past year or two, lend themselves to this mode of embodied viewing, using sight to trigger sensations elsewhere in the body. The range of media is broad. Adina Bricklin’s Mantle refracted (2015) appears to be three cyanotype prints collaged together to form one contiguous image of pictures on a mantle. In fact, Bricklin created translucent, hand-drawn negatives with graphite on vellum by tracing inverted photos on an iPad and used those drawings to make cyanotype contact prints on watercolor paper, printed on the windowsill in sunlight. An image that appears to have nothing to do with drawing thus turns out to originate squarely within even the most conservative definitions of drawing. This serves as a reminder that many of the works, whether sculptural assemblages or fabric capes, may have originated in the act of drawing, whether or not the traces of that act are visible.

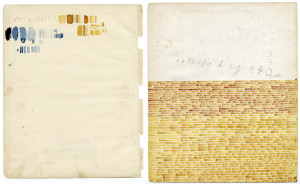

Kate Castelli’s small, meditative canvases (Not a Circle II, III, and Ochre Alphabet, 2015) are exercises in mark making, with a watercolor gradation of tally-lines that recall Paul Klee and Lee Ufan. Theodore Cantrell’s large canvas, The Horizon Never Reach #2 (2015), fades from creams to blues, marked with blurry Xs and Os. It is a landscape that summons to mind the cave paintings of Lascaux. A rudimentary wooden claw hanging next to the work hints at a process of rubbing and scratching. The other memorable mark-making was Liz Nofziger’s Ground Lock (2015). Viewers the same height as Nofziger who stand on a red dot on the floor can see how the blocky red window decals run parallel to buildings and fences outside the gallery. This exercise in empathic viewing asks visitors to assume the artist’s subjectivity by crouching or standing on tiptoe.

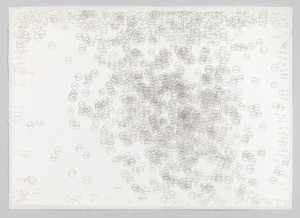

Further down the conceptualism spectrum, Andrew Mowbray’s Heads or Tails (2015) is a poster on which the artist recorded the outcomes of more than one hundred coin tosses by tracing the circumference of the coin and inscribing the word “heads” or “tails” inside it. This drawing is an event score as well as the documentation of a chance procedure and an aesthetic object. Viewing it, one might imagine jingling spare change in one’s pocket or fingering the ridges around the edge of a coin. Chance is also a structural element of Julie Martini’s Particle 1 (2015), a large sheet of pink marbled paper with black ink around the edges and a swirling bubbly core. Both works were produced by a combination of freely flowing materials and rigidly controlled actions, both of which the images themselves evoke.

Five films offer test cases for theories of the medium as essentially haptic. Recall that Walter Benjamin compared the filmmaker to a surgeon and Virginia Woolf described the eye that “licks” the screen. In Kolbeinn Hugi’s Weekend Warrior (2014), an actor runs his hands under the warm stream of a urinating cow. (I saw Hugi perform on electronic instruments wearing only a loincloth in Reykjavik two years ago and was equally mystified then). Rebecca Newhouse’s video of two hands playing at close range (Collage, 2015) and Gary Setzer’s of a man tracing a line through the desert (Horizon Pull, 2015) are among the more literal illustrations of the manual theme. Both seem like offshoots of the 1928 film Hands, in which disembodied hands dance in space to a dissonant piano score. This, however, is not the sensation of filmic tactility to which Benjamin or Woolf referred. While other works in the exhibition conjure abstract feelings of hapticity in the viewer’s fingertips, these videos offer straightforward depictions of that sensation and thus appear less poetic in this context.

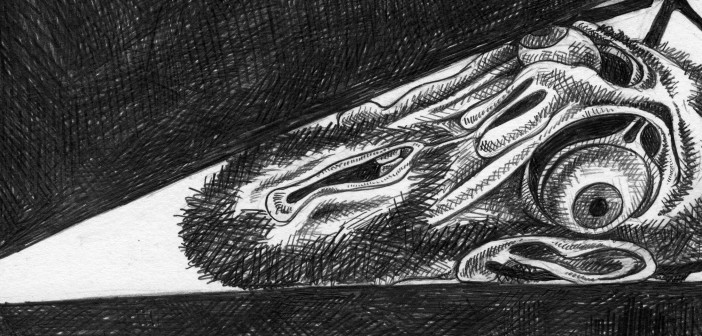

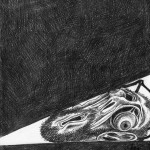

For more conservative drawing fans, there are a handful of works in graphite on paper. Jenene Nagy’s p5 (2013), a tour de force pencil drawing composed of quasi-abstract geometric forms, is filled-in from edge to edge without a sliver of bare paper showing through. Brian Cirmo’s Cone and Angle (both 2013) also offer a familiar notion of drawing, melding ghoulish forms amid densely crosshatched negative spaces. Ariel Freiberg’s Feminine Delinquency (2015) is an eroticized cluster of charcoal marks on torn paper. Works like these immediately register as drawing but do not provoke tangible sensation; they do not call out to be touched like Lenny Schnier’s flaccid nylon stockings (Little Red, 2014) or Heather Clark’s Astroturf tapestry (Catoctin Mountain, 2015).

The curator of Feelers is Susan Metrican, a Boston-based artist whose practice is committed to trompe-l’oeil effects. Instead of object labels, she equips visitors with a map of the gallery that includes the artists’ names and titles and dates of works. A short wall text near the entrance highlights connections between the novel Flatland and “drawing’s inherent encounter with flatness.” Given the array of thinkers who have addressed this problematic, Metrican’s choice of a Victorian novel seems arbitrary. The analogy works for and against the exhibition. The nineteenth-century grounding has the advantage of preceding modernist polemics against the embodied experience of art (those of Michael Fried for instance), and thereby debunking the myth that flatness and surface only became dominant values under high modernism. The novel shows that discourses of flatness predate pure visual abstraction by decades. Flatland’s veiled critique of the caste system also becomes increasingly apt throughout the exhibition as a metaphor for the ossification of medial boundaries in modern and contemporary art. The drawback of leaning on this shrewd novel, however, is that it provides an interpretive model so far-reaching as to risk losing all specificity. What art, after all, cannot be “felt,” either physically or emotionally?

Feelers is a provocation to think broadly about what drawing does. In this exhibition, it functions as a mode of abstraction: drawing draws from an image or experience as abstract art abstracts from the real. This exhibition examines not a specific medium but a process of drawing from the world and embodying a relationship to the forms and textures within it.

Feelers is on view at The Mills Gallery through December 20.

- Brian Cirmo Angle, 2013 Pencil on paper 10 x 8″

- Andrew Mowbray Heads or Tails, 2015 Silver point on paper 36 inches x 47 inches

- Kate Castelli Ochre Alphabet, 2013 Ink on vintage paper 17.5 inches x 25 inches