Welcome to Six Block Rule, a series of conversations considering art openings, panels, exhibitions and more happening in the Boston area. Titled after the idea that viewers should take that distance before making critical comment, Six Block Rule seeks to present an honest, accessible dialogue about art happenings that shape the cultural landscape and contemporary art community. In our first installment, senior editor Leah Triplett Harrington and board member Emily Glaser discuss Lorraine O’Grady: Where Margins Become Centers on view the Carpenter Center’s Sert Gallery. This is O’Grady’s first exhibition at the Carpenter, and Where Margins Become Centers presents seminal works from her four decades of conceptual practice.

EMILY: Hi Leah. I'm so glad we're doing this.

LEAH: Hey Emily, me too!

EMILY: So on Thursday we decided to go see Shahryar Nashat: Skins and Stand-ins at the CCVA. I've never been to the CCVA building before. You've been, right? I was surprised at a Brutalist building feeling so light. The design elements are all right there, so walking through the concrete and wood and metal you're always aware of the space. And not in the way you're aware when in, say, City Hall.

LEAH: I have--it's one of my favorite buildings in town (or just period). It's Le Corbusier's only North American building. It's so easy to navigate. You know exactly where you are.

LEAH: The Nashat show looked really interesting. Since we were at the opening of both shows, there were many people there, and we couldn’t quite see the work. We will have to make a trip back! But we were also interested in Lorraine O’Grady, who were both weren’t terribly familiar with.

EMILY: To be honest I had never heard of her. I'm glad that I fixed that.

LEAH: I knew her Michael Jackson photos (The First and Last Modernists, 2010).

EMILY: Okay, let's talk about going through the exhibit. It's from five different bodies of work, but rather sparse.

LEAH: Which makes sense in hindsight...they give you a few iconic pieces from each body of work. Each work on view has so much to…to unpack, to use an oft overused phrase…so it’s nice that every work has its own breathing room. Most works have their own wall within the literal white cube gallery space. And with the vitrines of archival material in the middle, you can absorb a work, then go back to delve into the archive. I think it was a really effective balance between work and archive.

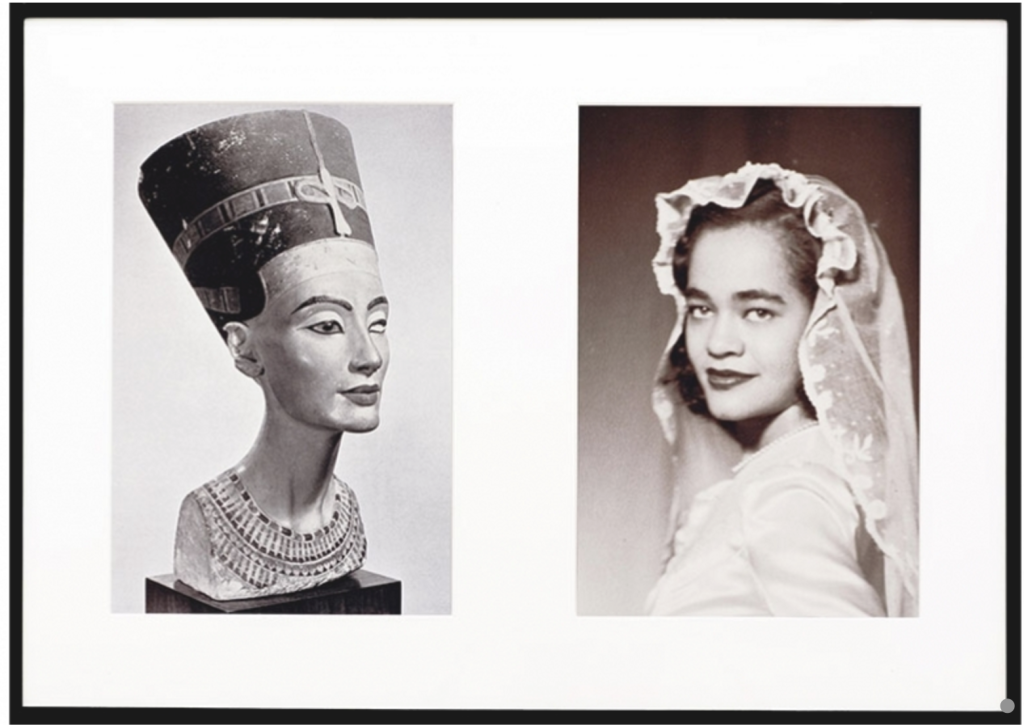

EMILY: The first piece that caught my eye was from Miscegenated Family Album (1980/1994). There are two diptychs. One photo in each is a traditional Egyptian statue and the other is a photograph of a woman from the 20th century. In Miscengenated Family Album Nefertiti faces this woman in the 1980s and it's this really stunning reflection of facial expressions and lines. I like work that either imitates or is a found photograph that happens to look like another better known image--is there a word for that?--that I always find intriguing. I guess that's what the internet is.

LEAH: So two independent images that come to mean something else.

EMILY: Yeah, and that other meaning is kind of an inside joke.

LEAH: And inside jokes are always predicated on culture, time, personality, and place.

EMILY: An image of a Nefertiti statue says anthropology, ancient, education--it's pretty dry and academic. Looking at it compared to a woman who is probably still alive reminds you that Egyptians modeled this after real people. And punchline: we still do exactly the same thing.

LEAH: And we do it almost exactly the same when we document seminal moments, particularly in women’s lives. We pose the same, and adorn ourselves surprisingly similarly.

EMILY: Right. In the posing woman, her jawline and even her rolled up sleeve reflect the statue. But she could be in a Jordache catalog or something.

Lorraine O'Grady Miscegenated Family Album (Sisters I), 1980/1994. Courtesy of Alexander Gray Associates

EMILY: We saw Lorraine in the gallery, briefly! She is, what, 81 or 82 now. And had such an energy and joy about her.

LEAH: It's really unusual and impressive that she began her artwork in the late 1970s. If she was born in 1934 that would make her in her 40s... According to the fantastic *free* publication at the Carpenter, O’Grady studied economics and Spanish literature at Wellesley College, and after graduating in 1956, she served as an intelligence analyst for the US government, a translator and a rock critic. Talk about varied experiences…as James Voorhies, who curated the exhibition, writes in the publication, O’Grady “…burst onto the New York scene in the early 1980s with her performance Mlle Bourgeoise Noire (Miss Black Middle-Class), a beauty queen persona in a pageant gown made of 180 pairs of white gloves, whipping a cat-o’-nine-tails at openings and shouting poems against the racial divides permeating the black and white art worlds.” I think it’s fascinating that she had so many experiences, in so many fields, before and after the Feminist movement and came to her art practice towards middle-age.

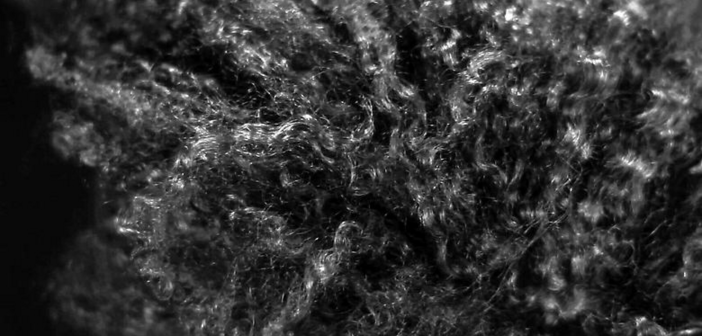

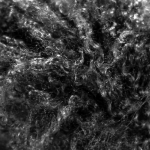

EMILY: Let's talk about the hair video, Landscape (Western Hemisphere) (2011).

LEAH: It's very disorienting, starting with the presentation: coming into the dark, very small room. The video is noisy, too: this ambient white noise that could be a fan, a vacuum, a dryer…

EMILY: Like you're supposed to be plucked out of your element and then you get reoriented except there's this screen, and this sound...

LEAH: And it's blowing around this material that you slowly realize is HAIR! It must be her HAIR! So then you are curious and weirdly transfixed--looking at someone else's scalp and hair in a way that you never can look at your own.

EMILY: I'll say it: at first I thought there were bees involved.

LEAH: Well, it's that humming sound!

EMILY: Because of the buzzing sound from the fan or dryer in the video. The cuts in the video are so subtle, you don't even notice that it's zoomed out. Suddenly the hair is very obvious.

LEAH: Overwhelmingly obvious.

EMILY: The statement I read in that is: distance matters. Getting too close or too far from something, you lose some valuable perspective.

LEAH: I hadn't really thought about that aspect...the idea of something you think you know...like what hair looks like and then you change the perspective and it's utterly unrecognizable to you.

EMILY: What do you think the title means?

LEAH: I think it's really literal. Her work is where the subtle, marginal things that are so politicized become central. What do you think?

EMILY: On a personal level, when you're a marginalized person--because you're a woman, a woman of color especially, or whatever else--you're still the center of your own experience. A lot of her work seems to be about refusing to deny her experience and showing that to other people.

LEAH: What do you think the "where" means...? Is it a mental space, or is it the gallery space? Especially in the context of Harvard: such an Institution, and one that only admitted women around the same time that O'Grady started making work.

EMILY: I think both. The gallery space is where someone actually has to show up to see the work..."Where" mentally refers to the idea and willingness to go to Harvard for an art show, as well as being open to whatever you find there and hopefully giving you some insight on someone else's experience and step outside of your own.

LEAH: Meaning, people need to feel both comfortable and welcome to see this work, both feelings that aren’t always equated with the word “art gallery.” The viewer needs to feel like they are in a comfortable space to relax their preconceptions or inhibitions about conceptual work, while also feeling invited to be challenged, both intellectually and morally.

LEAH: And what you see in this work is totally dependent on your mental space...it's highly individual work that can only be responded to individually. Maybe that's another reason for all the white space between works.

EMILY: Ha! White space. Right. The work was literally on the margins, whereas most of the walls were blank.

LEAH: She's playing what that literal white cube in the Carpenter. You literally have to go into a center within the Carpenter to see the work that she’s made, and all works are placed along the margin, or the membrane of the space. And in that way you come to appreciate more how the margin is defined by the center, but likewise how the center can be defined or evolved by the margin.

EMILY: I think her work is incredibly playful. "I'm going to show images of Michael Jackson next to Baudelaire" who does that? It's amazing that a series of mostly black and white images—which from afar resemble a typical fine art exhibit—contain such humor and strong statements about how we look at each other and at our expressions.

LEAH: Yes! It's really comical but also sharply transgressive. I hope people in Boston see this show. I think it's one of the most topical and important presentations of what identity and race means in society and in history.

EMILY: I think O'Grady makes the conversation about race and identity more accessible through humor and, hopefully, art as well. “Modern” art can feel opaque, but her work, if you spend time looking, invites absolutely everyone to relate in some way.

Where Margins Become Centers is on view at the CCVA’s Sert Gallery until January 10, 2016. A talk will take place on November 17 from 6:00-7:30pm at Harvard Art Museums.

- Lorraine O’Grady Body/Ground (The Clearing: or Cortez and La Malinche. Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, N. and Me) 1991/2012 Silver Gelatin print. Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates

- Lorraine O’Grady The First and the Last of the Modernists Diptych 1 Red (Charles and Michael) 2010, Fujiflex print. Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates

- Lorraine O’Grady Still from Landscape (Western Hemisphere) 2010/2011. Video: 10 minutes. Courtesy Alexander Gray Associates

- Lorraine O’Grady Miscegenated Family Album (Sisters I), 1980/1994. Courtesy of Alexander Gray Associates