American Epics: Thomas Hart Benton and Hollywood, recently on view at the Peabody Essex Museum (now travelling across the country through fall 2016), was a stunning, densely-mounted and sharply focused show that brought to light the cosmopolitan side of a painter imbued with the wanderlust and social concerns of a hard-drinking Woody Guthrie. Along with Grant Wood, Benton (1889-1975) is probably the most well known American Regionalist painter. With a fierce contempt of modernism and abstraction, Benton’s compositions are clearly influenced by High Renaissance compositions and the exaggerated bodily contortions of Mannerism. His subjects run the gamut from religious and classical subjects to contemporary America in all its ethnic diversity and income disparity. The past six years has seen a notable body of literature on the artist: a biography from 2012 (Thomas Hart Benton: A Life by Justin Wolff), and a 2009 account of his mentorship and subsequent falling out with Jackson Pollock (Tom and Jack by Henry Adams) aimed to dispel the myth of Benton as a conservative yokel. Perhaps exhibits such as this will forward that agenda.

Centered on the importance of the film industry on Benton’s oeuvre, the exhibition ultimately asks viewers to consider the narrative, cinematic qualities in Benton’s work. However, this premise raises the question: how many artists working in the centuries before the advent of film used similar storytelling devices in their work? From the hieroglyphics of the Egyptians to Masaccio’s fresco cycle The Tribute Money to Edvard Munch’s fin-de-siecle Frieze of Life cycle, cinematic, narrative flow in art predates the medium of film by thousands of years. Benton’s appropriation of this device was hardly new, even when compared to his early, pre-Hollywood murals.

Benton’s involvement in the film industry began in 1915 when he was twenty-six years old. Hollywood had not yet been built and most American film production companies operated out of Fort Lee, NJ. As the young painter garnered work creating sets during the silent era, he was already predicting film’s storytelling capabilities as it might pertain to painting, particularly the American saga of Westward expansion as told through moving imagery in all of its changing compositions and sweeping story arcs.

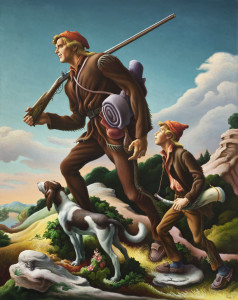

Thomas Hart Benton, The Kentuckian, 1954. Oil on canvas, 76 1/8 x 60 3/8 in. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of Burt Lancaster. Photo courtesy of LACMA. © Benton Testamentary Trusts/UMB Bank Trustee/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

Benton’s initial focus was on America’s mythic icons and the rural downtrodden from the West and Midwest: African Americans, dirt farmers, starving but hopeful pioneers, gunslingers, and cowpokes, among others. His peregrinations during the 1920s gave him the opportunity to experience first-hand the “old manners… and old prejudices,” as he wrote in his autobiography, of these vast, rural landscapes and their inhabitants. While he enjoyed playing the roll of a simple chronicler of rural American life, the folk singer Burl Ives (who almost lost his nose to Benton’s teeth in a drunken brawl), said of him, “He liked to be… one of the gang but he wasn’t. He was an introspective, thinking man… but he didn’t want anybody to know it.”1 Despite this seeming disconnect between the artist and his chosen subjects, it was the barn dances, the farmers tilling the fields, and the covered wagons plodding West in the great American expansion that occupied Benton’s career in the years before he temporarily relocated to Hollywood.

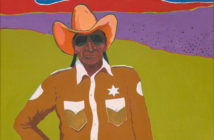

A decided leftist, Benton was involved with the labor-sympathetic Populist Movement and condemned social injustices such as the Native American genocide and the subjugation of African Americans both vocally and in his painting. Nevertheless, his work has been heavily criticized for what have been read as racist depictions of African Americans and Native Americans. To this day debates continue to rage over racism within Benton’s work. Take for example the exaggerated features in such work as 1942’s Negro Soldier: while some see the jutting face and enormous lips as a repulsive caricature, it is impossible to ignore the work’s simultaneous depiction of a determined, advancing soldier and a brave and honorable American defending the very country by which he is oppressed. Viewers may find it difficult to reconcile such potentially offensive, stereotypical portrayals of African Americans with simple, tender works such as the 1936 lithograph Huck Finn that highlights Twain’s portrayal of the famous interracial friendship as, hand-in-hand, they smile at one another as they drift down the Mississippi. In his review of the exhibition catalog in the New York Times Book Review, Mark Harris criticizes Benton’s portrayals of African Americans as “stand[ing]at a fascinating juncture of folklorism, exaggeration, respect, and incomprehension,”2 an assessment that in turn prompted a letter from the artist’s son, who teased out Harris’ racial allegations and fervently denied any such leanings on the part of his father.3 But Benton’s tolerance was far from all-inclusive. His almost pathological contempt for homosexuals was born of the belief that they had taken over the art world. Further anti-racist arguments crumble before Benton’s World War II paintings presented in the last room of the exhibit. Exterminate! (1942) depicts slant-eyed, buck-toothed Japanese soldiers alongside menacing, Teutonic marauders trampling upon skulls, emaciated baby carcasses, and dying American civilians. During the height of anti-German and Japanese sentiment in the 1940s, such images were common in propaganda. By modern standards it is cruel caricature and stands as a time capsule of a country’s wartime xenophobia.

Thomas Hart Benton, The Lost Hunting Ground, 1927-28. From the mural series American Historical Epic, 1920-28. Oil on canvas, 60 1/4 x 42 1/8 in. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Bequest of the artist. Photo by Jamison Miller. © Benton Testamentary Trusts/UMB Bank Trustee/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

The 14-part mural American Historical Epic (completed in 1925), created before Benton’s arrival in Hollywood, is a focal point of the exhibition: a work at once devoted to chronicling a young country’s ingenuity and unique history alongside its more shameful episodes. Shown at the Peabody Essex as a combination of originals and reproductions, this sprawling series has a narrative flow cinematic in its presentation. The work drew criticism from liberal camps for Benton’s inclusion of the Klu Klux Klan (he maintained that it was intended not as a glorification but as an historical record). On the other end of the spectrum, right-leaning audiences did not like their racial myths distorted (the mythic cowboys and Indians of the American West as imagined by his predecessor Frederick Remington – an overt racist - sat more soundly with the conservative camp), and so despite the popularity of his historical works with a public newly fascinated with the American West (largely due to film), Benton drew criticism from liberals and conservatives alike. It was in cinematic terms that Benton defended such imagery to both sides, describing his narrative as an “extended drama” rather than “a scholarly history.”

Unable to fully please the average, racially biased American, and having alienated the New York/Paris art world with his folksy, regional style and his increasing vocal contempt for modernism in general and abstraction in particular, he left New York for Kansas City in 1935. Writing about this decision, Benton said, “…since the depression, [New York] has lost its dynamic quality.” While the public was not always thrilled with his politics and historical depictions, Benton’s figurative work proved ever more refreshing to an audience whose aesthetic ideals were routinely discarded by the East coast elite in favor of abstraction. So welcome was his figurative style that in 1934 Life Magazine asserted his status as America’s most famous artist (complete with his picture on the cover), thus starting his relationship as a correspondent for the magazine. In 1937, Life sent him to Hollywood to cover the film industry.

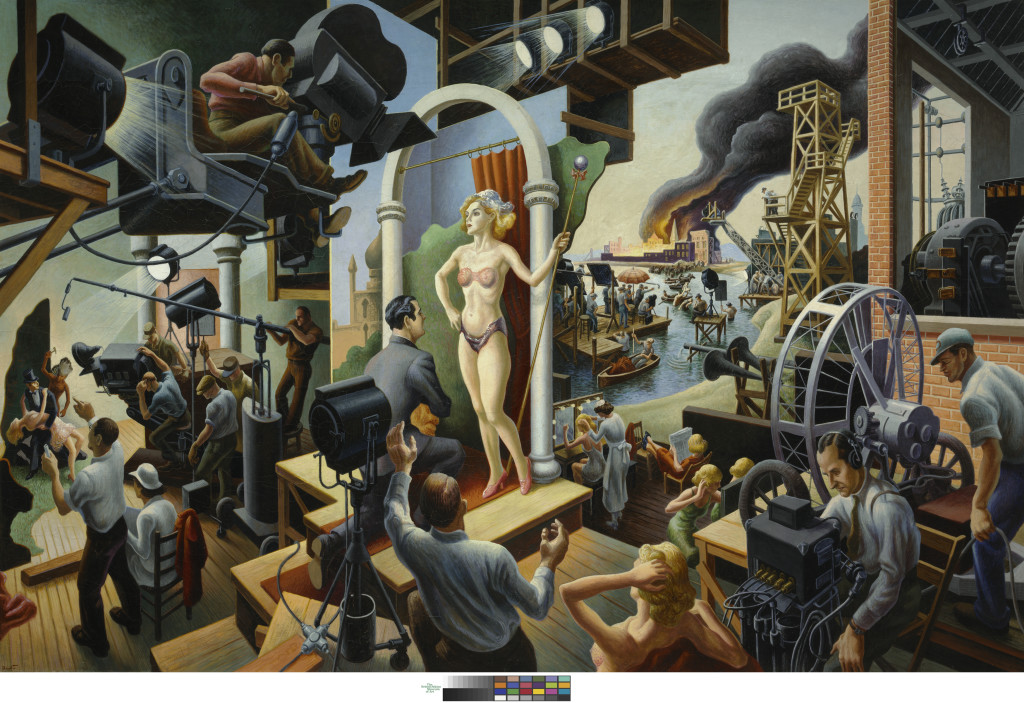

Benton ultimately spent seventeen years traveling back and forth from Hollywood as commissions from studios proliferated. Upon his arrival on assignment for Life, Benton created detailed drawings of equipment (cameras, editing rooms), set builders, designs, and the fat cats behind the scenes gathered around boardroom tables. One of the great drawings from these “visual notes” titled Young Executive (1937), captures the smug confidence of one such bigwig: well fed, cigar in his mouth, wheeling and dealing on the telephone. Pictures like this exude contempt for the industry as a whole. Benton insisted that he had no interest in the other Hollywood reporting going on around him, saying that his work was “not by any means an authoritative study of the movie industry”4, and that film executives were no different from the Wall Street blowhards back in New York. To him, his work in Hollywood was an assignment plain and simple, albeit an assignment wherein he absorbed the aesthetics of film and began applying them to his paintings in the form of ever more accurately sketched plans and narrative themes. He had long used his trademark devise of constructing set-like detailed clay models from which to work, not unlike sets and storyboards to which he was exposed.

Thomas Hart Benton,

Hollywood, 1937–38.

Tempera with oil on canvas, mounted on board, 56 × 84 in.

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Bequest of the artist.

Photo by Jamison Miller. © Benton Testamentary Trusts/UMB Bank Trustee/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

The artist’s time in Hollywood as a (very minor) celebrity did put him in touch with some of the great luminaries of the age. Benton was surprised to find himself one of the most popular artists in the country (Life Magazine having had a sizable hand in this), and the tide of public opinion quickly turned in his favor. This was also due to his mythic portrayals of the American West, concomitant with the cinematic masterpieces of director John Ford’s Westerns. The two instantly recognized a kinship in their approach to creating art – both had a deep interest in sweeping epics depicting the American frontier. Ford maintained that his films were about identity and citizenship disguised as adventure and romantic melodrama, reflecting his passion for history. The main characters in his films- gunslingers, farmers, soldiers and displaced pioneers- are often engaged in attempting to create a civilized community in unsettled frontiers despite their social differences. Having found a kindred spirit in Ford, Benton’s attention shifted away from depictions of the Hollywood money machine to the content and characters of the films it produced. In a series of six sublime lithographs produced for Ford’s 1940 film version of Grapes of Wrath, Benton created a series of psychologically penetrating portraits of its main characters. The work’s disarming simplicity was a huge marketing risk when compared to the bright colors of most promotional imagery used by theaters, however the risk paid off; audiences and studios responded favorably. These prints were quiet, irresistible gems within the show at Peabody Essex.

The exhibit does achieve its aim in bringing to life Hollywood’s Golden Age not only as it pertains to Benton’s paintings, prints and drawings, but also through the somewhat hokey (though effective and rather fun) props and theater sets Benton had a hand in creating. These unexpected pieces are scattered throughout the galleries, along with projected excerpts from films with which the artist was involved. Still, the focus of the exhibition - Hollywood’s influence on Benton, its foreshadowing in his earlier work (e.g. American Historical Epic) and its influence on his subsequent work – is surprising when one considers how infrequently his work has been presented in the 21st century. So while American Epics was both admirable and exhaustive in its theme, an artist of Benton’s stature deserves a broader overview sometime in the near future, particularly in our current historical moment, where figurative painting is once again alive, well, and a hot market commodity.

---------------------

TOURING SCHEDULE

Peabody Essex Museum | www.pem.org | June 6, 2015 - September 7, 2015

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art | www.nelson-atkins.org | October 10, 2015 - January 3, 2016

Amon Carter Museum of American Art | www.cartermuseum.org | February 6, 2016 - May 1, 2016

Milwaukee Art Museum | www.mam.org | June 9, 2016 - September 5, 2016

---------------------------

1 Tom and Jack: The Intertwined Lives of Thomas Hart Benton and Jackson Pollock (New York: Bloomsbury Press, 2009), 22.

2 Mark Harris, review of American Epics: Thomas Hart Benton and Hollywood, New York Times May 29, 2015 Sunday Book Review.

3 Thomas Piacenza Benton. Letter to the New York Times June 5, 2015 Sunday Book Review.

4 Thomas Hart Benton, “Hollywood Journey,” in American Epics: Thomas Hart Benton and Hollywood, ed. Austen Barron Bailly. (Munich: Prestel, 2015), 22.

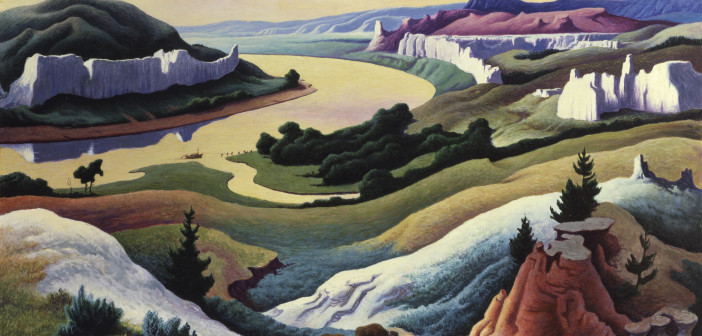

- Thomas Hart Benton, Lewis and Clark at Eagle Creek, 1967. Polymer and tempera on Masonite panel, 30 1/2 x 38 in. Courtesy of the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art, Indianapolis, Indiana. © Benton Testamentary Trusts/UMB Bank Trustee/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

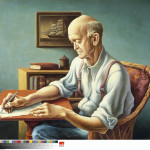

- Thomas Hart Benton, New England Editor, 1946. Oil and tempera on gessoed panel, 30 x 37 in. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, The Hayden Collection, Charles Henry Hayden Fund. © Benton Testamentary Trusts/UMB Bank Trustee/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

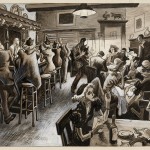

- Thomas Hart Benton, Thursday Night at the Cock-and-Bull. It’s the Maid’s Night Out, 1937. Ink, watercolor, gouache, and graphite on paper, 12 5/8 x 16 3/4 in. Private collection. Photo by Larry Ferguson Studio. © Benton Testamentary Trusts/ UMB Bank Trustee/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

- Thomas Hart Benton, Hollywood, 1937–38. Tempera with oil on canvas, mounted on board, 56 × 84 in. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Bequest of the artist. Photo by Jamison Miller. © Benton Testamentary Trusts/UMB Bank Trustee/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

- Thomas Hart Benton, Portrait of a Musician, 1949. Casein, egg tempera, and oil varnish on canvas, mounted on wood panel, 48 1/2 x 32 in. Museum of Art and Archeology, University of Missouri-Columbia, Anonymous gift. © Benton Testamentary Trusts/UMB Bank Trustee/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

- Thomas Hart Benton, Self Portrait With Rita, about 1924. Oil on canvas, 49 x 39 3/8 in. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution/Art Resource, NY. © Benton Testamentary Trusts/UMB Bank Trustee/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

- Thomas Hart Benton, The Kentuckian, 1954. Oil on canvas, 76 1/8 x 60 3/8 in. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Gift of Burt Lancaster. Photo courtesy of LACMA. © Benton Testamentary Trusts/UMB Bank Trustee/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

- Thomas Hart Benton, People of Chilmark (Figure Composition), 1920. Oil on canvas, 65 5/8 x 77 5/8 in. Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington. Gift of the Joseph H. Hirshhorn Foundation. Photo by Cathy Carver. © Benton Testamentary Trusts/UMB Bank Trustee/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

- Thomas Hart Benton, Bootleggers, 1927. Egg tempera and oil on linen, mounted on Masonite panel, 68 3/4 x 74 3/4 in. Reynolda House Museum of American Art, Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Museum purchase with funds provided by Barbara B. Millhouse. Courtesy of Reynolda House Museum of American Art. © Benton Testamentary Trusts/UMB Bank Trustee/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

- Thomas Hart Benton, The Lost Hunting Ground, 1927-28. From the mural series American Historical Epic, 1920-28. Oil on canvas, 60 1/4 x 42 1/8 in. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri. Bequest of the artist. Photo by Jamison Miller. © Benton Testamentary Trusts/UMB Bank Trustee/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.

- Thomas Hart Benton, Shipping Out, 1942. Oil on canvas, 40 x 28 1/2 in. Property of the Westervelt Collection and displayed in the Tuscaloosa Museum of Art in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. Photo by Chip Cooper. © Benton Testamentary Trusts/UMB Bank Trustee/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.