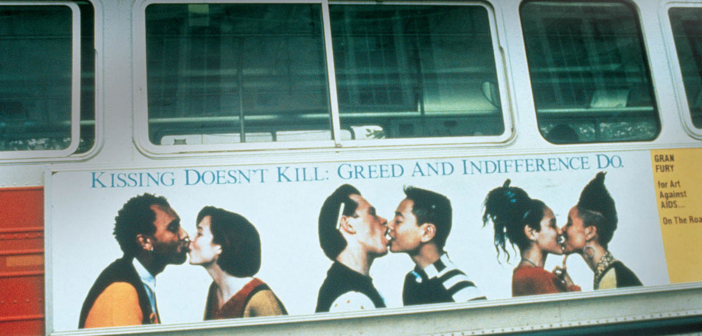

On Thursday, February 28 the Art Department at the University of Massachusetts Boston, in conjunction with Associate Professor of Art History David Areford's course Art 210: Queer Visual Culture, welcomed the artist Avram Finkelstein for an hour-long lecture and Q&A on his past work in art and activism. Avram has exhibited his work in prestigious venues across the United States and abroad, including the Venice Biennale in 1990. His work has been collected by a number of museums including the Museum of Modern Art and the New Museum in New York. In the 1980s he was a member of two important artist collectives: the Silence=Death Project and Gran Fury. Examples of this work were featured in two recent exhibitions Regarding Warhol at the Metropolitan Museum of Art this past fall and This Will Have Been: Art, Love & Politics in the 1980s which closed on March 3 at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston. UMass Boston's Harbor Gallery showcased Avram’s recent work in an exhibition entitled Lifelines, curated by American Studies Professor Aaron Lecklider and organized by the gallery's student director, Kevin Benisvy, which closed March 14. The following questions were posed by the students of Art 210: Queer Visual Culture and the audience in attendance.

..................................................

One of the things that struck me about what you said is that the canon diminishes radicalism, which I agree with. At what point in your or Gran Fury’s career did this work start to become canonized? And did you think there is a feeling of hypocrisy or misuse of that within the group?

The first answer: almost immediately. Almost simultaneously to the spinning of this tale. . . the community’s response to it was this way in which it was being described in the press. [It was described like] ACT UP was media-savvy. Which is a compliment, I suppose, but of course it’s a self-reference. What the media is saying is, "You speak our language." That gesture of approbation is actually an attempt to neutralize the radicalism of it. What it’s saying is, "You share our hopes. You share our desires. You share our language. You’re a part of us." Now of course that’s all true and there were many outlets in the media who were similarly affected and in the art world, as well. We were basically giving voice to something that other people didn’t know how to articulate. So I’m not saying that the responses to the instant canonization or historicization were not valid. It’s incredibly valid. Everyone was responding in the way they best knew.

But to answer your question, there was tremendous tension about all of those things you’ve asked about. I made it a practice to never participate in those conversations while people were dying. It isn’t until now, that the AIDS crisis is over, I feel conversely. I now feel obliged to historicize it. We’re going to be gone soon, this generation of people who experienced it. After that, the history will be a crapshoot, it’ll be up for grabs. They’ll either get it right or they’ll get it wrong about this moment so I need to participate in this conversation now.

The reason I drew some distinctions between the Silence=Death project and Gran Fury was that Silence=Death came out of a moment of isolation and with a full political consciousness about what was happening. Gran Fury came out of a community response that was already up and running. The Silence=Death poster came before ACT UP. So if you think about its intention, about its radical intention, the fact that it’s anonymous and that we wanted to escalate with it the call for riots and that we chose to be anonymous so that we could call for those illegal responses; that’s a radically different thing from throwing your hat in the ring after the community response is already running, after people are paying attention, after [prominent display]windows were offered to us by a not-negligible institution in New York City.

The thing about ACT UP that I didn’t really go into much depth about [in my lecture]is that it was like any community situation—people had varying levels of politicization, yet everyone was being politicized on the ground. No matter how political you were, you were becoming more political. But there were people in my affinity group (a sub-group of people in a larger organization) who were committed to being arrested and with whom I was doing illegal things. One member of my affinity group who I trusted with my life—more radical than anyone I had ever met—had voted for Reagan before his boyfriend had become sick. So clearly there were many sub-strata of politicization within ACT UP. This was true for Gran Fury as well. While [Gran Fury] did start because of the offering by Bill [Olander] of [the New Museum’s]windows, I came right to the ACT UP group after speaking with Bill Olander. I didn’t want any part of the museum project.

Let me explain why. When I went to school, it was the height of Situationism. The institutional critique that you see in some of the work that I’m describing goes incredibly deep for me. So that’s why when Bill came to me with the proposal for the museum I had no interest in the project. But I felt like, in deference to ACT UP, it wasn’t mine to decide whether ACT UP should avail themselves of this project. So I brought the project to the floor and I said, "Is anyone interested in working on this project, if so, meet me in the back of the room and we’ll decide on a time and date," and I basically organized the meeting, went to the first one, and then I didn’t participate in that installation at all because of my own politics.

But many of the people who did were in the Whitney [Independent Studies] Programs, a lot of them were working artists, they identified as artists, so the way Gran Fury constituted itself was as an art collective in my estimation. It was certainly far less political a collective than Silence=Death was. Consequently there were huge tensions around what kind of funding we should accept, how we should navigate that. . . We were almost always invited as a collective to do installations overseas and everyone would go but me. I actually mentioned that we were invited for the Venice Biennale and I didn’t block us doing it because obviously we did, but there were tremendous tensions around it and I didn’t go to Venice because I had my own politics about these things so I refused to participate in it.

You mentioned earlier about how you were able to get images into the public sphere. Of course, media is very different now with the internet. Do you think that would have made the projects less effective?

I mentioned a bit about this during an interview I did with WUMB earlier. We (Gran Fury) were asked [at one point]to help a group of students form a collective and do some collective work for some cultural production. And we were considering what that might look like. The majority of the members felt like we might have nothing to offer because the social context was so different, that "Why would anyone want to listen to me talk about posters and billboards?" To which I said, "Well, I have a couple of responses to that."

We’re told that media relevancy. . . in order to stay relevant we need to employ certain types of new media. My question though is, who is telling us that? What is the meaning of that designation? There’s capital involved. We’re told we need a certain type of phone, not that you need a smartphone, that you need a certain type of smartphone. We’re being told that by the media that is fully invested in this technology race. We’re also told by them that this is relevancy. There’s this sort of upward-spiral, a frenzy surrounding various media and my contention is that while those media are incredibly valid and if I was making this work now I’d be working in that medium, but these new technologies are simply delivery systems for content and ultimately it’s content that is the meat of the work rather than the delivery system. Content is what’s relevant.

Second, if other communication strategies are in fact bankrupt, then why does HBO, large movie companies, etc. still advertise in subways, on busses? Why do they still invest in that? And the difference between the way we organize politically and the way we organize culturally are vastly different. The question mark always comes up about the Arab Spring and how essential new media technologies were to the organizers of that resistance movement. An activist friend of mine who is an environmental psychologist points out that while information technologies are essential for communicating after people have already decided to go to a demonstration (We’re moving to here; The cops are there; This spot, not that spot), what we can’t necessarily count on new technologies to do is to get people to go there to begin with. Because everyone knows finding a thing on the internet, unless you know what you’re looking for, is very, very difficult. It lacks, in environmental psychological terms, serendipity. You’re not encountering it in a physical space and it’s not visceral in the same way. In the way that things that are virtual give you the sense of distance in the same way that historicization and canon does, it enables you to not participate but still feel like you are participating. So all of those things need to be considered when you’re talking about new media.

. . .Ultimately, I made this whole entreaty to the collective and really was digging in my heels about it. I live in New York, and New Yorkers are very parochial. They all stay within the ten-block radius of where they live—that’s where they shop, that’s where they go for a cup of coffee. So there are these set of parishes inside of it and these physical spaces are very important.

I said to Marlene McCarthy, who is in the collective and quite a brilliant artist, "The poster comes for you where you live." She said, "What could be more ‘where I live’ than this [smartphone]in my pocket?" And I said, "Yeah, of course you’re right about that, but there is something about a physical space that is very different than a virtual one." When we continued in this conversation I said, "Don’t get me wrong, if in fact we’re talking about collaboration with students, I would want to work with the computer labs at NYU out of which came the Foursquare geo-location program. And I would want to know if there was a way to reverse-engineer recognition softwares [sic]so that we could pick the pockets for the contact lists of people coming into the gallery to send out email blasts. So it’s not to say that there aren’t huge amounts of opportunity to collaborating with them and new technologies and I would be willing to explore that as well."

Something that I found in the scholarship around the art surrounding AIDS and ACT UP [and Gran Fury]is the relationship between cooptation and distillation. What I almost never hear spoken of in scholarly literatures or personal narratives is about the backlash and resistance at the time. Do you have any experiences as a member of both of these art collectives that speaks to that kind of experience as well?

That’s a really good question and it is sort of interesting to think why that piece of the story might be written out of any academic studies about it. Again, it has to do with the ideas that we choose to anoint as relevant or meaningful. . . I wrote a piece that got me into some trouble called "AIDS 2.0" where I evaluate the two documentaries (United In Anger and How To Survive A Plague) mentioned and I talk about canonization and what creates canon, who decides how we come to think of things. . .

There was a huge resistance to ACT UP. In fact, in the New York gay community, most of the gay organizations basically came out of the local Democratic Party. . . they were party hacks. And we were considered horrible and there was tremendous tension surrounding it.

I would say a backlash was visible when we would go around and photograph the graffiti, which was really hateful; to give us a sense of what actually was happening in the public sphere. There’s a tendency with artists who work in the public sphere to think, because we had spent so much time considering what the message was before it even hit the public sphere, we’ve already had the dialogue, but it’s not actually true until the work is in the public sphere. That’s when the dialogue begins.

With the first Gran Fury poster, we have a photograph with some [graffiti]saying "Scared Faggots Crap AIDS" or something like that. We were up against a tremendous amount of resistance, but I think that we reveled in it. It gave us a greater understanding of what actually was happening. In the same way that I was thrilled by lesbian activists taking our work and making it their own, I was not threatened by it—I was thrilled by it. There are also many things that we didn’t see, that we didn’t have to see, that I wish that I had gotten the chance to see in the public sphere. When the anti-abortion group appropriated Silence=Death, I didn’t agree with it, but the fact that this set of ideas has reached the vernacular in such a broad way that. . . We didn’t intend it as a slogan that would be that incredibly broad, but it turned out to be.

I many, many years later found out that my mom had actually seen the Silence=Death poster in the street but didn’t know that I had done it when she first saw it. She told me about it when she was well into her nineties and I was kind of flabbergasted by it. She said that she had realized that that phrase was so broad and had so many meanings and she began to refer to it as "the shot heard ‘round the world," which is very typical of my mom. She was so bombastic and idealistic, she was quite political and saw the world this way.

But like I said, we had worked for six-nine months on that and we had discussed the new math idea, the equivalency idea and all of the layers of meaning that that had. How piercing the vernacular just with that idea of an equation was going to be radical and have many meanings to many people. I’m not sure why there’s not heart for the telling of the complexity of this story, but for me, that’s the soul of the story.

For decades I’ve been trying to explain to people that Gran Fury did not design Silence=Death. The entire historiography has been compacted into this canon where all of the cultural production came out of one voice. But there were many collectives working in New York at the time. Some of the things that are most familiar to you were done by collectives you’ve never heard of. It’s not because there’s some nefarious subtext to history, although there of course is, but that’s not what’s happening here. What’s happening is history is an elevator pitch and we privilege the ideas that are easiest to say. Generalizations mask the messier, more disorderly, and most interesting points of our history. What’s true here is true of all history.

The language of advertising in the eighties must have had some sort of similar topical compression like [the one you’ve described in history]. Do you find that that topical compression and apparent divorce from overarching political philosophies is neutralizing? How did that play out in talks with Gran Fury where you’re making artworks that address the topic of AIDS awareness and getting medicine to people who are sick?

One of the women in my affinity group very early on pointed out to me that while the Silence=Death image was a great thing in terms of being an organizing tool and a communal way to give voice to a certain series of experiences, wasn’t there the danger that people within the community could also experience the work from a distancing perspective? But as she meant, and you’re completely right to ask this question, appropriating the voice of authority enables people to see you as authorized. It obliterates the possibility for people who are experiencing the moment themselves to see it from a resistance perspective, they might see it as an official set of responses rather than a resistance. I think that that’s true. A lot of that had to do with the idea that in advertising vernaculars branding is very much keyed into the same things that we were looking to attach to this idea about activism—ubiquity, the creation of its own literacy, the folk vernacular of communal experiences.

We were relying on those things but we were also paying the price for them and to this day when people refer to Silence=Death as the ACT UP logo I see exactly what you’re talking about at work. It could never be perceived as this messy, loose, charged political gesture of resistance. It can only be seen as a logo. In the same way that canon neutralizes dissent, the idea of referring to Silence=Death as ACT UP’s logo creates a whole series of assumptions about it. This was designed for the organization. By it being a logo it puts ACT UP on parallel footing to CitiBank. It intones participation and defangs the very nature of the organization just by calling this thing a logo. The mechanisms that are work within academic canon or art canon are very much at work in our culture at large. So you’re right about that and we were very aware about it.

What I’ll say about all of that is this: My dad was a [Communist Party USA] member who was completely thrilled with my work with ACT UP. But also completely burned out as a person who was a party member during the early twentieth century when it very much seemed like there was going to be a revolution in America. Let’s not forget, there were revolutions happening in other countries and there was a rise in the Labor movement. It was perhaps even a more political moment than the sixties. It was wildly political. It was so political that the New Deal had to be made, which has been thought of as a Socialist gesture, in order to prevent and be an end-run around the class resistance that was happening at the time.

Anyway, the last fight that [my dad]and I had was a screaming fight, and was over ACT UP. I told him about the things we were doing and he kind of smirked and said in a way that only a burned-out Leftie can do, "There will never be a revolution in America." And I said, you know, "Look, old man, I have two choices. One is to do nothing, in which case I know what will happen—people will continue to die. The other is to try something. Maybe it will work, maybe it won’t. If it doesn’t work I’ll try something else. There is no choice involved. So please don’t ever talk to me agency or engagement." You have a choice to make which is, how do you participate in the world? How do you adapt to the various questions we’re discussing? How do you make a way for yourself in the world and live with the consequences of those decisions? That’s what we do as engaged members of our communal experience.

The other thing that I’ll say about it: The Jew and the queer always knows that there is something else going on, that anything that can be given to you can be taken away. But not participating is complicit is some way. The queer knows how to find themselves in the language or insert themselves into the various levels of fucked-upness that exists in the world, but still how to participate and resist at the same time.

Do you think that the collective suffering that you’ve described is understood and keenly felt in the way that it should be by this generation? Do you think that there is an effective way outside of groups like Gran Fury to actually communicate that in its gravity?

I sit on the Steering Committee of the Pop-Up Museum of Queer History in New York, which is a sort of roving history project. As a consequence, I deal with young lesbians and gay men who are archivists, activists, academics, artists, academicians. I can tell you that there’s a huge hunger, there’s a huge awareness in New York in particular (and because you’ve asked this question, clearly that exists here in Boston as well) surrounding this material. So I do think that not just the queer, but the inquiring mind, looks through our history to try to find threads that relate to them or the lessons that aren’t being told. That is the reason why in academic settings we do so much reading and have so many conversations about meaning of truths that are given to us. It’s our obligation to glean the stories out of the written stories.

I will say that there is a moment around this material. Helen Molesworth’s show at Harvard a few years ago (ACT UP New York: Activism, Art, and the AIDS Crisis, 1987—1993) that then traveled to a couple of other locations; these two movies; This Will Have Been has already been in three locations; and then the many versions of performance art, writers, young writers, who are obsessed with this material and are trying to comb through it. There is a moment about this material and there is a huge awakening about this material.

Among people of our generation there is a lot of hand-wringing about the disengagement of this generation, but that is not at all what I’m witnessing whenever I speak about it. The simplest pieces of information. . . I can just see faces just completely lighting up. In the same way that it occurred to me that when I was being devastated by AIDS there was a community response to it that we might do a poster came to me because of the fact that when I was sixteen I saw posters in the street. Who knows what the people in this class will think, what they’ll make of that piece of information—the things that will happen as a result of you now knowing this story, this continuing story. So I don’t feel in any way feel any amount of despair about how this story is remembered.