The artist known as Katsushika Hokusai (he was to use thirty-one different names during his ninety years) is probably the most widely celebrated Japanese artist of the Ukiyo-e period of Japanese art. By 1760, Edo (now Tokyo) was probably the largest city in the world. The term Ukiyo-e, or “Floating World,” was not so much an artistic style (though woodcut and painting were its primary mediums) as it was a philosophical meditation on life’s transitory pleasures. The popularity of Ukiyo-e lasted from roughly the 1670s to the mid 1800’s; its gradual decline corresponded with Japan’s reopening to the West when, in 1853, despite centuries-long sovereignty under feudal shoguns in the service of Emperors, Japan succumbed to pressure from the United States to open to trade.

The medium of woodcut undoubtedly remains the era’s greatest and most lasting achievement, both for its graphic and enduring imagery, and for the inventiveness and labor of its technique.* The ease of creating large quantities of prints from these woodcuts made them easy to find and inexpensive to buy. Produced in vast quantities by large publishing houses employing numerous cavers, printers and papermakers, prints could be purchased as souvenirs for roughly the price of a small lunch.

The Museum of Fine Arts is home to the largest collection of Japanese prints outside of Japan, but despite the quality and focus of the collection, past exhibitions of Japanese prints have been small in size and generally confined to one room. Hokusai, on view through August 9, is like an answered prayer from the museum that mounted the world’s first exhibition of the artist’s work in 1892

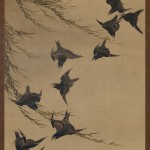

Hokusai includes prints, paintings, and manga (illustrated books done in woodcut) that, while organized by subject, also conveniently follow a rough chronology. It is the prints that dominate in their beauty and technique, as well as in sheer number; this is unsurprising as the artist is estimated to have executed between thirty to thirty five thousand print designs in his lifetime. The manga were generally intended for instruction, and include both figures for students to study, as well as shunga (erotica), intended for young brides-to-be or commissioned by prurient collectors. The large paintings on silk, mounted as hanging scrolls, feature such favorite themes as waterfalls, wildlife, and literary characters. Overall, the paintings are underwhelming, though the spectacularly crafted portraits and nature scenes, with their hidden, well-preserved brushwork, are still radiant. The deftly-painted large ink drawing Willow and Crows showcases an economy of strokes while still managing to imbue each bird with its own personality. The accompanying catalog essay by Sarah E. Thompson and Phillip Meredeth discusses the synergy between Hokusai’s prints and paintings, pointing out how the master occasionally used painting techniques in the creation of prints and vice-versa. While such crossover influences are expected from an artist who moved between mediums, the technical similarities between mediums are not obvious - even to the informed viewer.

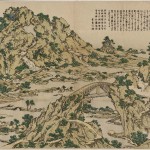

Along with the sublime (and sometimes positively trippy) prints depicting waterfalls and Mt. Fuji, Hokusai’s tranquil, transcendent bird and flower prints hold us in quiet awe. They are clearly the result of endless hours of careful observation, and seem strange for their concentrations of detail juxtaposed with expanses of color in wide-open skies. It is a marvel that a master of grotesque, exaggerated, and overtly sexual imagery could move so effortlessly between subject matter. View with One Hundred Bridges (c. 1823) looks out upon a craggy, fantastical mountainous landscape and is a feat of invention and fantasy that Hokusai claimed came to him in a vision.

A highlight of the exhibition is the famous series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, created while the artist was in his seventies. Original printings from this series are rare (as opposed to re-strikes printed after the artist’s death), and are among the most coveted in the medium. The Great Wave of Kanagawa (c. 1825) from Hokusai’s series – easily the most recognizable of all Japanese prints - has taken its place as the crown jewel of the set and the poster child for the exhibition. It is hard to argue with this decision, despite the ubiquity of the image. The technical prowess of the carving within the wave’s crashing cap creates ranges of blues and spots of foam that are both complicated and masterful, while the fine, subtle gradations of silver grey in the boat convulsing upon the crashing waters make it difficult to fathom the foresight needed to plan for the print’s execution. Given the assembly line system of print production, the artists themselves seldom (if ever) had direct involvement in the creation of the prints beyond an initial drawing. Hokusai’s apprenticeship with a print publisher as a teenager gave him a leg up in his grasp of the inherent possibilities and limitations of the finished product.

Most unexpected are the Patterns for Collage Pictures (Oshi-e) created between 1808-1813. These prints were made to cut and assemble into mini pastoral and stage settings populated by swordsmen, maidens, celestial spheres and animal onlookers. They are surreal, confusing and compelling even in two dimensions, with ingenious economy of space. Was this the planning of the master himself or a clever, experienced carver? We will never know, but they are prime examples of the synergistic relationship between artist and workshop. To our unbridled delight, they have also been reproduced and assembled.

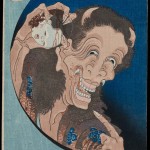

Of the many so-called Ghost Story Prints Hokusai created, a scant six are included in the MFA show. While these are among his most famous prints- simultaneously gorgeous and ghastly- it is nonetheless a feeble showing. Given the popularity of such imagery coupled with Hokusai’s penchant for the eerie, fans of the genre will be disappointed. A single manga page, titled The Gods of Conjugal Happiness (1821), is the sole representation of Hokusai’s enormous output of shunga, for which he is revered by connoisseurs of the genre. In this erotic scene, engorged cock heads and gaping vaginas are presented as jewel-like, daintily packaged gifts. That there is just one, sadly diminutive example of the genre included is a clear indication of the show’s conservative focus. The puritanical bias toward pleasing scenes and the relative scarcity of the erotic and macabre prompted one visitor to remark “This is Boston, after all.”

While the exhibition’s exclusion of certain subject matter is grievous, other curiosities regarding stylistic choices on the part of the artist and the printers also beg mentioning. Horizontal, ovular shapes frequently jut abruptly from the borders of landscapes, denoting hyper-stylized clouds or, more often, the delineation of middle and distant backgrounds. For an artist accustomed to Western perspective and the receding and diminishing of form, this aesthetic filler comes across at worst as a lazy crutch and at best as an unusual decorative contrivance. An overwhelming use of bright, unsubtle cobalt blues in the bokashi (the fading off of a color achieved by inking in gradations) is expressed here as a haze at the top of a print. The device is somewhat repetitive, and can be explained by the pigment’s sudden availability after years of prohibitive cost.

As an octogenarian, Hokusai bequeathed himself with his final nom-de-guerre, The Old Man Mad With Painting. Like the barefoot Giotto drawing in the dirt with a stick or Klimt strolling along in his yard in a robe among his cats, Hokusai became a wandering fixture in the local community; in the last years of his life, he was often seen roaming through Edo’s pleasure district, dressed in rags, his quill never leaving his hand, drawing virtually anything that came into his line of sight. At eighty years old he declared that he was beginning to understand the ways in which he might truly depict life as it exists - not in pleasing pictures of prostitutes and waterfalls, but as it appears in its simplest form to the human eye. During the last five years of his life he renounced all his former work as trifles: amateurish, mere practice. Upon his deathbed in 1849, he expressed a wish for fifteen more years, believing that should he live to be 105, he would finally achieve the perfection he sought. As it is, he came as close as anyone has before or since, and the MFA’s knockout show is a testament to this.

- Willow and Crows Katsushika Hokusai (Japanese, 1760—1849) 1841 (Tenpo 12) Hanging scroll; ink and color on silk * William Sturgis Bigelow Collection * Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- One Hundred Bridges in a Single View Katsushika Hokusai (Japanese, 1760—1849) about 1823 (Bunsei 6) Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper * William Sturgis Bigelow Collection * Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Laughing Demoness (Warai Hannya), from the series One Hundred Ghost Stories (Hyaku monogatari) Katsushika Hokusai (Japanese, 1760—1849) about 1831-32 Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper * William Sturgis Bigelow Collection * Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- The Amida Falls in the Far Reaches of the Kisokaidô Road (Kisoji no oku Amida-ga-taki), from the series A Tour of Waterfalls in Various Provinces (Shokoku taki meguri) Katsushika Hokusai (Japanese, 1760–1849) about 1832 (Tenpô 3) Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper * William Sturgis Bigelow Collection * Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Fine Wind, Clear Weather (Gaifû kaisei), also known as Red Fuji, from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjûrokkei) Katsushika Hokusai (Japanese, 1760–1849) about 1830–31 (Tenpô 1–2) Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper * Nellie Parney Carter Collection—Bequest of Nellie Parney Carter * Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Under the Wave off Kanagawa (Kanagawa-oki nami-ura), also known as the Great Wave, from the series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjûrokkei) Katsushika Hokusai (Japanese, 1760—1849) about 1830—31 (Tenpô 1—2) Woodblock print (nishiki-e); ink and color on paper * William Sturgis Bigelow Collection * Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

*Readers unfamiliar with the process and production of Japanese prints may read a description in my review The Creative Process in Modern Japanese Printmaking.

There is also an excellent display case showing tools, original blocks, and proofs in various stages, as well as a video demonstrating the printing process, within the exhibit.