At the press preview for Chicago in L.A.: Judy Chicago's Early Work, 1963—74 at the Brooklyn Museum, curated by Catherine J. Morris, Sackler Family Curator, with Saisha Grayson, Assistant Curator, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, Judy Chicago recounted a story that encapsulated many of the paradoxes that define her artistic practice. While at a recent opening, Ed Ruscha mentioned to Chicago that Richard Prince had been working on a series of car hoods, something that Chicago had done in the 1960s. What would it mean to put Richard Prince and Judy Chicago in the same room? After all, Chicago has frequently said that men can be feminists as well. Moreover, Prince’s early work, especially his now-canonical re-photographed cowboys and couples, has been seen as a move to deconstruct the heterosexual gaze in advertising. Could it be that Prince and Chicago are both searching for a more inclusive art history through differing methodologies? Might Chicago’s effervescent car hoods, which were criticized by her teachers for rejecting the tenets of hard-edged minimalism, as well as Prince’s evocations of the precarious nature of Americana, be partners in dismantling gendered or sexual norms?

With this in mind, I began to wonder what could be characterized as feminist art, and, more fundamentally, how feminism can be represented at all. Is it represented solely through "feminine" or "feminist" imagery? Surely not. Could a feminist impulse be found in a particular way of handling a given medium? With shows across the country of Chicago’s work, ranging from her earliest forays into minimalism to her current sculpture projects, we are at a perfect place to reconsider the role of identity politics in the arts beyond the iconic The Dinner Party. Opening up Chicago’s career, as well as feminist art generally, to a more rigorous critique is necessary to uncovering a nuanced understanding of how minority voices can find a platform for expression and critique.

William J. Simmons You have said you want to be a part of art history while also forging a new art history.

Judy Chicago Well, I would have to. There has to be a new art history in order for me to be a part of it, because I don’t fit into the old art history.

WS I’m constantly struggling with the issue of how feminist art, or art that deals with identity issues, is pushed into a separate space.

JC Susan Fisher Sterling, the director of the National Museum of Women in the Arts, called me today, and she would tell you, just as I would tell you, that the goal is equitable institutions. But we are so far away from that. As I have been saying about all these shows around the country, I’m occupying between 20,000 and 30,000 square feet of what Elizabeth Sackler refers to as museum "real estate." There is not a major museum in the world that would accord that much space to a woman artist. That is what would be required to do a real retrospective of my work. So until that changes, we have to have alternatives. I have a national retrospective as opposed to a single institutional retrospective.

We have to have institutions of our own; we have very few. After 40 years of activism, there continues to be incremental institutional change. There’s been a dramatic change in cultural consciousness in terms of gender, diversity, sexual orientation, ethnicity—in terms of identity. But that has simply not been adequately translated into institutional change such that we do not lose our work, which has happened for centuries. Women’s cultural production was lost until John Perreault wrote that incredible article in Artforum on Marsden Hartley.1 Gay and lesbian identity was not identified in contemporary art. I still remember reading Perreault’s art historical analysis of the painting of the man with the flower behind his ear. Never had anybody broached Marsden Hartley’s sexual orientation in relation to his work. As soon as John broached it, you saw Hartley’s whole body of work differently. Why does there need to be the Leslie Lohman Museum of Gay and Lesbian Art? For the same reason there needs to be the Sackler Wing at the Brooklyn Museum and the National Museum of Women in the Arts. Otherwise, our voices are lost.

WS Are we searching for a way to bring feminist work together with other artists who might not be tackling that subject matter? Or are we looking for separate spaces?

Returning to what we were thinking about earlier, what would it mean to have a Judy Chicago/Richard Prince show for instance?

JC I’m not sure it makes sense to have all of Richard Prince’s work next to mine. How about a show of his car hoods? That would be interesting. Andrew Perchuk did a talk at the Pennsylvania State University Judy Chicago Symposium about my work in relationship to Ed Ruscha and Robert Irwin. Perchuk is working on a book on Southern California artists about three other guys and me. He has talked about the emptiness of Ruscha’s photo books and juxtaposes that with Womanhouse in terms of architectural space in Los Angeles. Here’s Ruscha saying, "Here’s the California landscape—no people," and here’s Womanhouse, which is full of human content and subject matter.

WS That makes sense because that would mean that space is always politicized.

JC Right. The one step Perchuck hasn’t made is that he still thinks Ed Ruscha’s work is not gendered and mine is. Actually, the absence of content and the absence of subject matter could be gendered. I would like to see that argument. How does it relate to the fact that men are not supposed to express emotion? How does that construct of masculinity translate into art devoid of content?

WS In the same way that there’s a tension between art that is emptied of content and art that is content driven, there’s a similar push and pull of absence and presence when it comes to gender. I think that goes back to the issue of whether one should talk about Judy Chicago in a lecture on feminist art or one about Southern California art.

JC Well, both. The art historian Frances Borzello in The Dinner Party: Restoring Women to History positions my art within minimalism, Southern California finish fetish, and feminist art. I cross contexts, and it is incomplete to only talk about my work in terms of feminist art.

WS That gets me to another question. There’s this need in your work to express a specifically feminist point of view.

JC I say it differently. I actually say that what I have tried to do is create a female-centered art-making practice wherein the female experience can be a path to the universal in the same way that the male experience has been confused with the universal. I think what matters is that when you walk into The Dinner Party, it is probably the only monumental work in any museum in the world that you know was made by a woman.

WS I’m always troubled by something when doing research about your work. There is a part of your art that is trying to access this mode of representation that women have been unable to have because of patriarchal norms. But that does not mean that every single essay about your work has to say that everything looks like vaginas.

JC It’s not true. There was a particular period of my work where I was trying to formulate a female iconography, but I do not think that The Holocaust Project is any less feminist than The Dinner Party. And there are no vaginas or vaginal forms. Anything that is not masculinist appears to people to have something to do with identity—necessarily to do with identity—even when it’s not about identity.

WS I think there’s a constant push and pull of whether work by a feminist artist has to be feminist all the time.

JC What does that mean to be feminist all the time? Also, the definitions of feminism evolve. Feminism has changed and evolved for me. By the time I finished The Holocaust Project, I had come to a new place where I had begun to see the oppression of women in a huge global system of injustice that dehumanized whole sections of humanity. Was it feminist, for instance, when I did Thinking About Trees? I think some people are very confused about what feminism is.

WS This is why your earlier work needs to come to the fore. It offers an opportunity to rethink the way we have thought about feminism and art thus far and expand the conversation. There is something so valuable about thinking about the female form and its exclusion from art history. As you point out in Institutional Time: A Critique of Studio Art Education, the medium itself is gendered because women did not have access to academic training. At the same time, all this work of yours helps us think about the many different ways feminism can be represented. This is what I am trying to get at: how can feminism be represented?

JC In as many ways as the masculine has been represented! So that means feminism has infinite potential. What is feminism? It is really challenging the male hegemony in the most fundamental way in terms of how we organize systems of learning, systems of behavior, what we value—everything. And that’s why it’s taking so long!

WS Well, it’s a big project to undertake!

JC I think one of the problems is that different people define feminism differently. For some people, feminism is just "I want equal rights! I want equal pay!". That’s not feminism for me. Feminism for me is what I’m talking about in Institutional Time; it is a centuries-old goal.

WS There are so many different ways of expressing feminism. I’m thinking back to when we were discussing my piece on Nicole Eisenman and Amy Sillman—"Notes on Queer Formalism." Sillman’s work has nothing that one would typically call—on a wall text maybe—feminine or feminist. People have said that Sillman’s abstract work, in its layered elements, interesting color combinations, and quasi-corporeal elements, there is a search for some sort of interiority—something inside the medium, inside the artist. How does a work of art exteriorize or make visible its feminism if it is not explicitly dealing with feminist imagery?

JC I think you can go back to Georgia O’Keefe and say that until the development of abstraction it wasn’t really possible to directly express women’s own experience. If you look at O’Keefe’s work, Miriam Schapiro’s work, Joan Snyder’s work, Mira Schor’s work, even some of Lee Krasner’s work, although less explicitly, or Harmony Hammond’s work, you see abstract work that I think you could argue has managed to do that.

WS That returns us to the tension between content and medium or materiality. You have said of your work that it is content based. There was a great quote of yours, "If it is not perceived that my work is about the nature of women, then all the other things in my art are invisible."

JC That is interesting, because what is happening now is that, even in my abstract works like Flesh Gardens and Fresno Fans, the content is now understood. It wasn’t always understood. I can still remember, after I had finished Pasadena Lifesavers, Mark di Suvero saying "Judy, I could look at these for the rest of my life and have no idea they’re about cunts!" It was a big change to the time when the young art historian Jenni Sorkin came to me and said that her generation was passing around black and white images of my early work because they could read it. Now people can talk about the expansiveness, the color, the openness, while understanding the emotive and sensate content in that work, and until that got understood, it’s true; the rest of it wasn’t perceived.

WS So in your work, there’s a way to reconcile content with formalism?

JC That’s what I’ve struggled with. That’s what I worked on very deliberately. That’s what Catherine Morris’s show at the Brooklyn Museum looks at—how my early work was spilling over with content and then I moved away from it into more formal art-making. I wanted to be taken seriously. I decided I was going to set out to bring my content together with my formal language. The artist Clay Ketter said something regarding the Frieze Masters show about "muscular feminism"—how I managed to create work that was openly female-centered but had a kind of muscularity that you don’t necessarily associate with it.

A lot of people commented that one of the things they were blown away by in the Brooklyn Museum show was that, at a time when there were few visible female artists, I was working at such a large scale. I was already working in a scale that we associate with men, which is what I have tried to do. I have big ideas and I thought there was no reason why I couldn’t frame my ideas in a major format. I thought some of my ideas were major ideas. Women tend to work small because they don’t think their work is sufficiently important to take up a lot of space.

WS That goes back to what you said before about art being a universal language that stems from an individual experience.

JC It can be. Often it’s not. It is so cryptic. I learned to talk in tongues. You can see it at the Brooklyn Museum. I decided not to do that.

WS So in that search for a universal, feminist form of expression, how does your engagement with the medium work with that goal?

JC I choose the medium based upon what I have to express. Unfortunately, they couldn’t show Autobiography of a Year at the NYEHAUS/MANA Contemporary show. I wanted to explore my personal feelings as I went through that year. So I worked small and intimate and on paper to allow for very direct expression.

WS I remember that one of the things you told me the first time[pdf]we did an interview together is that central to your practice is learning your history as a woman. I have been thinking a lot about history lately, especially with the show up at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study’s Schlesinger Library at Harvard University. It seems that history, now and in your early work, was almost a medium in and of itself. A lot of your early work only survives in documentation. In that sense, the archive is central to your practice. You have this interesting relationship with your early work in which nobody really understood it, but now that we have this distance and documentation, we can really look back. I’m trying to think of another artist who embodies this urge to cherish the past while always looking forward.

JC There are these artists who say, "I’m not interested in my early work. I only want you to look at my recent work." My career is so different. Now, I’m time traveling at all moments. I could be in the 1960s in a show. The New Mexico Museum of Art is doing a show of the New Mexico years. David Richard Gallery is doing my most recent work. It’s interesting. I always wanted to be a part of art history, and I put my faith in art history through all those years when my work was completely not understood. Eventually, art history came through for me. It just took a really long time.

WS It’s so conceptually and emotionally moving—the role that history can play in your contemporary practice, as well as your willingness to look back, to rethink, and to reconsider. Finally, there was a lot of criticism of The Dinner Party.

JC That’s an understatement!

WS I juxtaposed The Dinner Party with Song of Songs, thinking about how the former is trying to get at a woman’s history and a woman’s form of expression, whereas the latter retains that element but seems to be more ambiguous. It seems to encompass more. I’ve been thinking about how the development of your work could be a barometer for the development of feminist and queer theories.

JC That’s interesting. At Penn State, the historian Jane Gerhard talked about the culture wars. When they discuss what happened around Andres Serrano and Robert Mapplethorpe, they don’t include what happened with The Dinner Party. Gerhard discussed the overlap between feminist and queer theory. This is another slant on what you are talking about. Why was what happened with The Dinner Party in the United States Congress less important than Serrano’s Piss Christ and Mapplethorpe’s photographs? It does raise issues about what you are talking about regarding the development of feminist and queer histories. Sometimes they overlap and sometimes they separate.

- Judy Chicago (American, born 1939). Rainbow Pickett, 1965/2004. Latex paint on canvas-covered plywood, 126 x 126 x 110 in. (320 x 320 x 279.4 cm). Collection of David and Diane Waldman, Waldman Family Trust, Rancho Mirage, California. © Judy Chicago. Photo © Donald Woodman

- Richard Prince. Gomper, 2007. Fiberglass, wood, acrylic and bondo. 67 1/2 x 54 x 5 in. (171.5 x 137.2 x 12.7 cm). © Richard Prince. Courtesy Gagosian Gallery

- Judy Chicago (American, born 1939). Birth Hood, 1965/2011. Sprayed automotive lacquer on car hood, 42 7/8 x 42 7/8 x 4 5/16 in. (109 x 109 x 10.9 cm). Courtesy of the artist. © Judy Chicago. Photo © Donald Woodman

- Judy Chicago (American, born 1939). Polished Stainless Steel Domes (Small), 1968. Polished stainless steel, each 2 x 5 in. (5 x 12.7 cm); 15 x 15 x 4 in. (38.1 x 38.1 x 10.2 cm) overall. Courtesy of the artist. © Judy Chicago. Photo © Donald Woodman

- Judy Chicago (American, born 1939). 3.5.5 Acrylic Shapes, 1967. Formed acrylic, 10 x 24 x 24 in. (25.4 x 61 x 61 cm). Collection of Penny Plotkin. © Judy Chicago. Photo © Donald Woodman

- Judy Chicago (American, born 1939). Silver Blue Fan, from Fresno Fans series, 1971. Sprayed acrylic on sheet acrylic, 60 x 120 in. (152.4 x 304.8 cm). Collection of Schaeffer Projects. © Judy Chicago. Photo © Donald Woodman

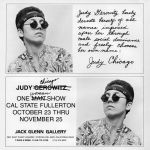

- Name-change announcement for Judy Chicago exhibition at California State College, Fullerton, October 23—November 25, 1970. Artforum, vol. 9 (October 1970). Courtesy of the artist.

This interview took place on April 11, 2014 in New York City, and has been edited for length and clarity.

[1] Perreault, John. "I’m Asking—Does It Exist? What Is It? Whom Is It For?" Artforum (November 1980): 74-75.