So why doesn’t the imaginary island-nation’s environs sound particularly felicitous? As an urban planner, More wasn’t particularly creative. Life in Utopia sounds, if anything, aesthetically monotonous. "He that knows one of their towns knows them all—they are so like one another, except where the situation makes some difference," More writes. "Their buildings are good, and are so uniform that a whole side of a street looks like one house." Each three-story-tall, flat-roofed cookie-cutter home includes a garden, and homes are swapped with the inhabitants of Utopia once a decade. This system, More tells us, was designed by the genius-king Utopus, beating Frank Gehry to the title of world’s first starchitect, "but he left all that belonged to the ornament and improvement of it to be added by those that should come after him, that being too much for one man to bring to perfection." Of course, More believed himself capable of creating the conditions for this perfection or else he would not have embarked on the thought experiment.

2. More is not entirely without sympathy for his creations. He gives short insights into the more intimate details of Utopian decoration, as in this evocative passage: "They have great quantities of glass among them, with which they glaze their windows; they also use in their windows a thin linen cloth, that is so oiled or gummed that it both keeps out the wind and gives free admission to the light." There is no particular need for the author to sketch out just how his ideal buildings might be illuminated, but one wonders if he wasn’t thinking of his own study more than anything else. It’s a flash of personal detail into an otherwise entirely impersonal system. Utopia has little to do with humans at the individual level and everything to do with the collective, and the faceless collective have no need for windows.

3. Living as he did in a time of political tumult, perhaps More imagined that by depicting his vision of an immaculate city he could insert it into the culture of his time and correct the present’s ills. The design of the town of Utopia, down to its buildings and ample glass windows, is a palliative for what More saw around him. Was sixteenth century England just terribly messy or is this need for an endlessly repeatable template with replica following replica simply an innate characteristic of the towns we have designed as Utopias? Plato demonstrates a similar obsession with sameness in his sketches of his own Utopia, which he names Magnesia, in his 360 BCE Laws:

There shall be twelve villages, one in the center of each of the twelve portions; and in every village there shall be temples and an agora . . . The artisans shall be formed into thirteen guilds, one of which will be divided into twelve parts and settled in the city; of the rest there shall be one in each division of the country.

Plato adds a dash of arithmomania into the housing of his ideal collective citizens, who are apparently content to live in structures determined by their rank and job, separated into arbitrary numbers of urban divisions and divisions of divisions. It’s a kind of architectural packaging plant, a city design that has more in common with the segmented protective casing of an egg carton than any community that humans have created in the real world. The practical is a lot messier than the theoretical. One wonders to what degree More and Plato actually thought about what it would be like to live in their machinations, if they considered how their mothers or friends or colleagues would feel existing within the strict confines they laid out in their theories.

Masked in the guise of a project for the public good, designing a Utopia is actually a supreme act of ego. These cities are impositions of will through architecture. But buildings are an imperfect vehicle for will since they must be populated by beings outside of the control of the architect. Utopian architecture ultimately fails because the buildings are designed as inanimate monuments to the mind of the creator rather than actual "machines for living," as Le Corbusier, himself an imperfect Utopianist, might have put it. In the end, Utopias are templates rather than homes. Homes, after all, are unique.

4. All Utopias share a certain sameness. When the 18th century French architect Claude-Nicolas Ledoux set out to design a saltworks for King Louis XV, he conceived of it as a patterned system rather than simply a building. The first plan he put together was composed of a diamond set inside a perfect square, a rigorous arrangement that fit with the Enlightenment ideals of rationality and the absolutist belief that a ruler could impose perfect society on their subjects through an enlightened social contract between the ruler and the ruled, not unlike the intentions of architects designing Utopias. Ledoux’s saltworks system featured colonnaded arcades running from workshop to dormitory to bakery, plus gardens for the workers to make extra money on the side. It was a template meant to be plopped down wherever Ledoux might decide, a self-sustaining entity that didn’t fit context into the equation.

Unfortunately, the project was too classical even for Louis XV—the king complained about the prevalence of columns, which he felt inappropriate for something so mundane as a factory. Ledoux’s chapel, relegated to a corner of the complex, was also improperly marginalized. So Ledoux started over. Rather than a diamond within a square, Ledoux created a circular design with the factory in the very center, symbolically suggesting the focus of the factory worker’s lives. Arrayed around the immense, austere factory in Ledoux’s design was an entire ideal city, a Utopia of labor, with forges, prisons, hierarchically apportioned dwellings, and gardens. A rendering of what the city might look like shows a symmetrical circle with avenues running out in the cardinal directions spreading into the countryside, an apron of large homes dissolving into forests and mountains. Louis XV approved.

The saltworks were completed, but the city wasn’t. Construction was interrupted by the French Revolution, which began to overthrow the aristocracy in 1789. And with such fascist architecture, who can blame the peasants? As Emil Kaufmann wrote in a 1952 treatise [pdf]on three "revolutionary architects" of the period, "Ledoux’s final objective is grandeur," rather than life.

5. In 1841, the influential Massaschusetts minister George Ripley decided to give up his stable position and start a Utopian commune following in the spirit of the Transcendentalists, who figured that if man could return to nature and live in harmonious austerity, things would be pretty good, or at least they could stop humanity from plunging into an Industrial Revolution nightmare of oppressed wage-slaves sweating over factory lines. Ripley sold 10 shares of investment for $5,000 each in his new venture, which would make money through selling farm produce. Yet at Brook Farm in West Roxbury, the land that Ripley purchased for his Utopia, the farm was slow to come—possibly because Ripley had no experience in farming.

What did make money at Brook Farm was a school in which pupils from all over the world were taught by the foremost intellectuals behind Transcendentalism. Perhaps this emphasis on education over more sustainable endeavors led Ripley to start thinking about ways to draw more wealthy philosophes to his cause. He started courting followers of Fourierism, the faddish philosophy of the French thinker Charles Fourier, which held that humanity would eventually be organized into self-sustaining "Phalanxes" (communes) of 1500 people based on agrarian economies. Like Ledoux’s saltworks, these structures were severely classical, laid out with sprawling wings of repeating facades. Construction of Ripley’s trial Phalanstery started during the summer of 1844. This description, from biographer Octavius Brooks Frothingham, Ripley’s contemporary, makes it sound rather pleasant:

The structure was of wood, one hundred and seventy-five feet long, three stories high, with spacious attics, divided into pleasant and convenient rooms for single persons. The second and third stories were broken up into fourteen "apartments," independent of each other, each comprising a parlor and three sleeping rooms, connected by piazzas which ran the whole length of the building and both stories. The basement contained a large kitchen, a dining-hall capable of seating from three to four hundred persons, two public saloons, together with a spacious hall and lecture-room.

Perhaps it was more like a college dormitory mixed with cafeteria and classrooms than agrarian Utopia. Unfortunately, paradise was not to last. Only two years after the wooden building was started, while it was still under construction, it burned to the ground, due, Frothingham notes, to "a defect in the construction of a chimney."

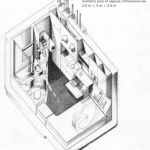

6. Utopian architectural plans are schemes to contain humanity like a hamster cage contains rodents: within strictly prescribed paths, in specific spaces designed for specific roles. In no building is this more apparent than Tokyo’s Nakagin Capsule Tower, a vertical stack of cubes each with its own tiny porthole. The structure was built in 1972 by the Metabolist architect Kisho Kurokawa for the efficient containment of Japanese salarymen. Each capsule contains a miniature environment with everything necessary for human life, including a shower (cold water only), bed, air-conditioner, and a wall-mounted television. Kitchens weren’t necessary with the profusion of noodle shops in the city.

The Metabolism architectural movement was supposed to provide for a certain amount of heterodoxy—the buildings were dynamic, changing shape, expanding and contracting to fit the needs of the city and its residents, a Utopian vision of mechanistic urban landscapes. However, the Capsule Tower was not quite dynamic enough. Today, it’s in a state of disrepair. Many of the capsules are falling apart, few have owners let alone actual residents, and as the building doesn’t fall under any particular landmark status, it’s under constant threat of demolition. So much for the revolution.

7. Utopic architecture presupposes a sameness of need, that all humans require the same basic things within their immediate environment to make a life. This theory was tested by a number of Communist dictators who decided that their civilians would be better housed in cookie-cutter compounds then allowed to keep their traditional dwellings. As Beijing was remade under Mao Zedong’s regime, citizens were organized into "work units," with each work unit housed in a designated complex that included everything the workers might need—small apartments jutting off well-lit corridors in several buildings, a planted courtyard, a daycare, a central kitchen.

In 2010, I lived in one of these worker’s unit compounds. I was one of the only foreigners in the place; I had taken over an apartment left behind by another expat. Half a century after the Communist Revolution and following a decade in which China started flaunting its status as a global political and economic superpower, the city was in an entirely different state than when my apartment building was constructed in the 1970s. Each apartment was still the same size and shape and the compound still formed a self-contained unit. My neighbors ate and yelled and played, the cooking smoke drifting out the windows into the corridor. Elderly women watching over young children exercised on a set of playground equipment fixed in the cement near the compound’s entrance. Life was everywhere.

Around the work unit, the development of Beijing had mutated since the ‘70s into a variegated sprawl. No two buildings looked the same; a decades-old silk market in the dun colors of the earlier Communist era stood across the road from a surreal group of curvilinear skyscrapers that seemed to float over a massive mall-like retail complex, if a mall were to be built inside the Death Star. The Utopic trappings of the work-unit scheme only went so far; while a certain paradise perhaps existed inside my compound, it was surrounded by condos mimicking the international argot of starchitecture.

8. Elsewhere in Beijing were two monuments to architectural egoism. Rem Koolhaas’s China Central Television Tower—affectionately known as the "Pants Building" for its twisted, two-legged structure that curved into a loop like a skyscraper folded on itself—had become an icon for the city. Koolhaas meant it as a postmodern riff on what a building might be. It turned out that what a building might be was, not a building. Mirroring the undemocratic, censored nature of the media in the country, the CCTV tower was forever fenced off from the public even though the architect designed it as a porous urban space. Some time after I left Beijing, Koolhaas’s tower on the edge of the pants foot print caught fire and burned catastrophically in what was rumored to be a firework accident. Score one for tradition.

The second attempt at remaking Beijing was Steven Holl’s Linked Hybrid, a collection of squat towers in an inaccessible (at least by public transportation) corner of the city that are connected by airborne passageways. These skybridges are lined with windows and are meant to provide public gym and recreational space for the residents of the Utopic "open city within a city," as Holl describes it. Each residential tower was color-coded in hues that look bright and vibrant in renderings but in reality turn drab and age toward a uniform gray. Holl also meant the compound to be "porous" but when I visited there was no one walking the wide, empty paving stones between the monolithic structures. The plaza in the center was mildewed. The towers showed no signs of residents save the guards stationed on the bottom floor of each one.

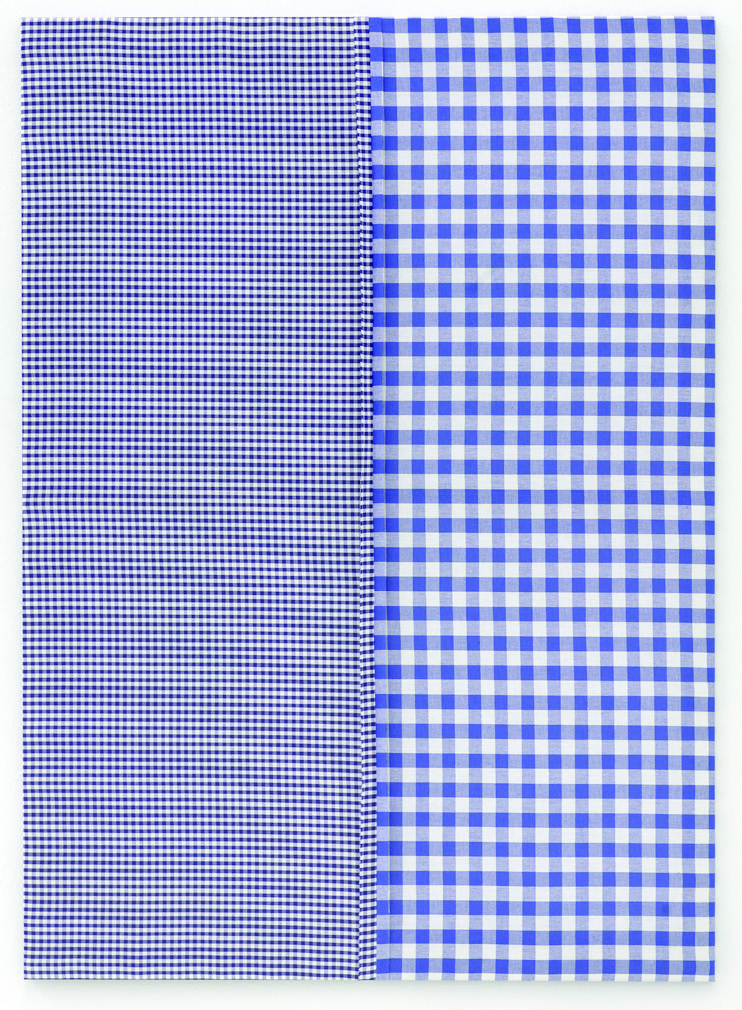

9. In the Utopian architectural subconscious, humans and buildings are equally replicable. Everything shares the same fundamental structures, no matter how different the patterns seem. And the patterns, and the buildings, and the structures always fail. It doesn’t matter if the template is More’s undifferentiated facades on the island of Eutopie or Ledoux’s geometric prison for workers or Kurokawa’s minimalist boxes. Whether the Utopian theory is actually built or remains imaginary, it always seems to fail or decay into irrelevance, a long-gone dream of a better world that never materialized.

After trawling through these various examples, it’s apparent that what the Utopias have in common is this vicious, monotonous sameness. In attempting to find a single solution that fits all of a community’s residents, or all of a society’s underclass, architects end up recreating the identical solution of fitting unique human beings into small boxes that nest in larger boxes, next to other boxes. Not Utopia, but Monotopia.

- Kisho Kurokawa’s Nakagin Capsule Tower

- Steven Holl’s Linked Hybrid

- Claude-Nicolas Ledoux’s second plan for the salt works.

- More’s Utopia

- Isometric plan of one of Kisho Kurokawa’s Capsules.