The subject matter of Williams’s work here seems to be the object matter derived from a highly rarified discussion of the photographic image as sign and its intended or non-intended signifiers. One is taken back to a classic postmodern (an interesting notion in itself) critique of the significance of the world's non-relation to its mechanical image. There remains a nagging rupture between representation and literal meaning that can be at times useful as a formalist divining rod of modernist aspiration and its contemporary misdirection from progressive purpose.

What struck me immediately in the installation is its flat institutional affect. The super-graphic wall text presents like an enlarged excerpt from the likewise industrially designed catalogue. This intentional use of the generic had a destabilizing effect initially, until one began to discern its MoMA-type homage to Bauhaus functionalism and deference to minimalist form. The artist’s attempt to radically intervene in institutional exhibition display by deconstructing MoMA’s presentational tradition continues throughout the show. Larger photographic images are hung below eye-level, decipherable wall labeling is eschewed in a right-angled floor plan that could have been derived from a Mondrian's "Oceans and Piers" series. Designated titles of individual works are presented as an inventory in the exhibition guide. All of these efforts signify as a kind of hyper-formalism that suffuses the rooms with the wan aura of bell-jar atmospherics.

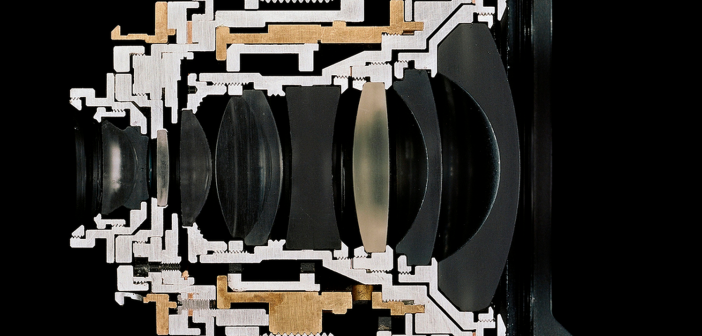

In the experience of individual photographs, one becomes aware of a reverence of process quality in their printing and mounting: the photograph as object, claiming equal aesthetic turf as painting and sculpture. Williams shares much tactical heritage with his approximate contemporaries in the so-called Pictures Generation in his presentation of the photograph as the pre-eminent medium to both embody and throw into question the authority of ‘the real’. A good example of this would be his series entitled "Eighteen Lessons on Industrial Design" which combines, under its appropriated title images of cross-sectioned camera lenses as machinic fetishes with more common items like a selection of minimal, stacked chocolate bars and other consumer items like socks and automobile tires. Rather than critique the commodity culture that spawned such imagery, Williams seems content to re-present these images with as little intervention as possible. Richard Prince's re-photographed advertisements and Sherrie Levine's re-photographed images of Walker Evans haunt these images. Working snugly within this radical tradition Williams also leans heavily on the plethora of critical theory generated alongside this generation of end-game tacticians. His reliance on this critical tradition, however, seems rather equivocal and often dilettante. Multiple tasteful references to the mystique of the socialist radical tinges his overall project with its tangential, but obvious allusions to the post-war, continental avant-garde (Jean-Luc Godard, Guy Debord) and Marxist theoretics (Walter Benjamin, Vilém Flusser). The show requests an embarrassing amount of postmodern indulgences while miming an ascetic apologia for modernist aspirations of purity and progress. It fits seamlessly into an institution like MoMA, which is compelled to reinvent its own radical credibility while constitutionally blind to the fact that its branding of the modern calcifies the transgressive aesthetic act into a recurring tradition. Williams’s work and installation tactics dovetails tightly into MoMA’s corporate identity. One takes away a disheartening sense of tragic capitulation of the artist to institutional dogma.

In reviewing specific works I noticed that many of the images (adopted, appropriated, re-photographed or otherwise estranged from their original contexts) contained within them coded visual referents to other more individual and classic images from the history of post-war art and film. One example is an image of a tipped over Renault sedan which is juxtaposed in the catalogue with Godard’s automobile pile-up scene from his dystopic film from 1967 "Weekend". If one is meant to correlate the filmmaker’s anarchical farce with Williams's cool and immaculately printed Renault in a way that valorizes art’s ability to be perennially transgressive, then Godard winds up getting the better value from this exchange. Williams in comparison comes off an enthusiastic spectator at the crash site of the modern, rather than affecting his own momentum to critically propel its dénouement. Another example is a photograph of a towel-headed model for what looks like a shampoo commercial headshot. Here Williams channels both Hitchcock (the Psycho shower scene) and Roy Lichtenstein’sGirl With Ball (1961). These stylish art historical referents, rather than bolstering a shared generic heritage, overshadow the curiously uninteresting banality of Williams’ images. If all authentic "high" art, to paraphrase Harold Bloom, relies upon troping and a turning away from not only the literal but also prior tropes, then "The Production Line of Happiness", in its attempted negation of the anxiety of turning away from prior influence, is artless in a way that debases even its popular and "low" art sources. Unfortunately this is not a new low nor is it the establishment of a base aesthetic that wants to obliquely comment on popular culture like Andy Warhol or even Jeff Koons. Williams’s overall project may be unified by his passion for the exquisitely crafted photographic fetish, and his longingly nostalgic gaze into a modernist land of entitled transgression, but it fails to transcend its fascination with its own dead-end theories of the whim of affectless art in the age of mechanical reproduction.

One can marvel at the consistency with which Williams has maintained his bearing of the high standard of postmodernist self-deflection. Such a doggedness of purpose has its own, perhaps unintended, consequence in topologizing the airless, lock-step administration of the deconstructivist project at large in the history of photography. There is a missed opportunity to change the subject, though, from fetish of the art historical to the temporalization of the fetishized image. The latter road might lead to a more phenomenal experience of the world as felt rather than just seen, reproduced. Even if Williams takes as his task the meaning of the photographic image this doesn't limit his options to simply residing within its rhetorical hall of mirrors. What is curious and most poignant about this show is the fact that one senses that the artist can intuit this need to displace the rhetorically over-determined for the critically unmeasured. The only repeated image in the show's catalogue is one of John Chamberlain's Couch (1980.) The sculpture is not a classic car-parts Chamberlain but a more idiosyncratic work, a urethane foam block trussed up with cord. The source for this object may have originated in a prosaic consumable, but gets transformed into a psycho-object fetish by Chamberlain. The inclusion of this work here functions like Matthew Barney's encapsulating of Richard Serra in his "Cremaster" series, as a presentation of the phenomenal as signifying trope, rather than affective symbol.

Williams’s intention seems to be to adumbrate a similar intensity of animus, to temporalize the progression of the fetish, into the overall structure of academically received notions of how the photograph skins the world: how it impoverishes phenomena and codifies the visual. He never quite achieves this intention, mainly because he is himself seduced by the disembodied image (and the attendant reams of critical theory concerning such) to the extent that he overloads the potentially free agent of re-presentation with too much of the institutional baggage of representation. His picture of the world is a map of what exists as already skinned and mounted.

- Christopher Williams ,” Cutaway model Zeiss Distagon T”, 2013. Pigmented inkjet print. Paper: 16 × 20″

- Christopher Williams , “Model #105M — R59C / Keystone Shower Door” 2005. Gelatin silver print. Paper: 16 x 20″

- Christopher Williams ” Model: 1964 Renault Dauphine-Four, R-1095″ 2000 Gelatin silver print. Paper: 11 x 14″ (28 x 35.6 cm); framed: 26 × 30″ (66 × 76.2 cm)

- Installation view of “Christopher Williams: The Production Line of Happiness” at The Museum of Modern Art, New York (July 27—November 2, 2014). Photo by Jonathan Muzikar. © 2014 The Museum of Modern Art